No standard protocol exists.

BY BLAKE FARMER, NASHVILLE PUBLIC RADIO

MEDICAL EQUIPMENT is still strewn around the house of Rick Lucas, 62, nearly two years after he came home from the hospital. He picks up a spirometer, a device that measures lung capacity, and takes a deep breath — though not as deep as he’d like.

Still, Lucas has come a long way for someone who spent more than

three months on a ventilator because of Covid-19.

“I’m almost normal now,” he said. “I was thrilled when I could

walk to the mailbox. Now we’re walking all over town.”

Dozens of major medical centers have established specialized

Covid clinics around the country. A crowdsourced project counted more than 400. But there’s no standard

protocol for treating long Covid. And experts are casting a wide net for

treatments, with few ready for formal clinical trials.

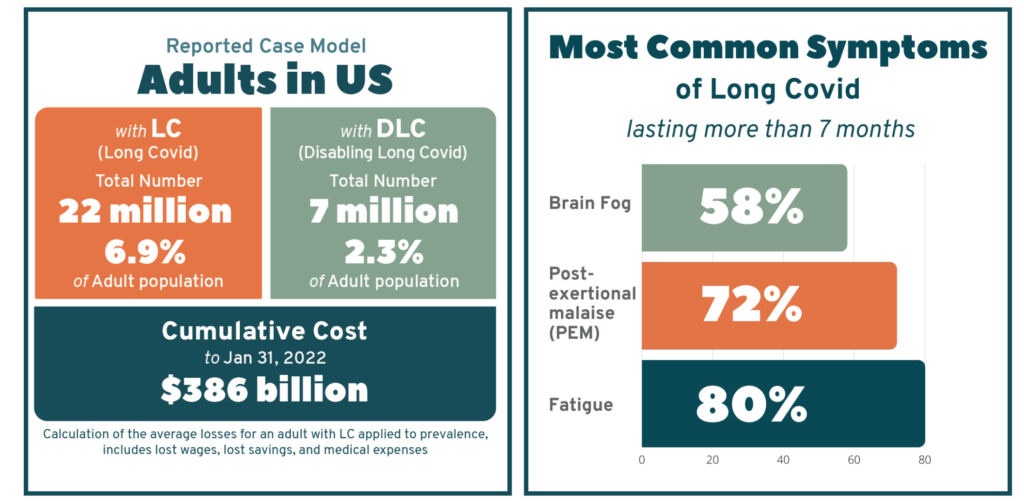

It’s not clear just how many people have suffered from symptoms of long Covid. Estimates vary widely from study to study — often because the definition of long Covid itself varies. But the more conservative estimates still count millions of people with this condition.

For some, the lingering

symptoms are worse than the initial bout of Covid. Others, like Lucas, were on

death’s door and experienced a roller-coaster recovery, much worse than

expected, even after a long hospitalization.

Symptoms vary widely. Lucas had brain fog, fatigue, and

depression. He’d start getting his energy back, then go try light yardwork and

end up in the hospital with pneumonia.

It wasn’t clear which ailments stemmed from being on a ventilator so long and which signaled the mysterious condition called long Covid.

“I was wanting to go to work four months after I got home,” Rick

said over the laughter of his wife and primary caregiver, Cinde.

“I said, ‘You know what, just get up and go. You can’t drive.

You can’t walk. But go in for an interview. Let’s see how that works,’” Cinde

recalled.

Rick did start working earlier this year, taking short-term

assignments in his old field as a nursing home administrator. But he’s still on

partial disability.

Why has Rick mostly recovered while so many haven’t shaken the

symptoms, even years later?

“There is absolutely nothing anywhere that’s clear about long

Covid,” said Steven Deeks, an infectious disease specialist

at the University of California-San Francisco. “We have a guess at how

frequently it happens. But right now, everyone’s in a data-free zone.”

Researchers like Deeks are trying to establish the condition’s

underlying causes. Some of the theories include inflammation, autoimmunity,

so-called microclots, and bits of the virus left in the body. Deeks said

institutions need more money to create regional centers of excellence to bring

together physicians from various specialties to treat patients and research

therapies.

Patients say they are desperate and willing to try anything to

feel normal again. And often they post personal anecdotes online.

“I’m following this stuff on social media, looking for a home

run,” Deeks said.

The National Institutes of Health promises big advances soon

through the RECOVER

Initiative, involving thousands of patients and hundreds of

researchers.

“Given the widespread and diverse impact the virus has on the

human body, it is unlikely that there will be one cure, one treatment,” Gary Gibbons, director of the National Heart,

Lung, and Blood Institute, told NPR. “It is important that we help find

solutions for everyone. This is why there will be multiple clinical trials over

the coming months.”

Meanwhile, tension is building in the medical community over

what appears to be a grab-bag approach in treating long Covid ahead of big

clinical trials. Some clinicians hesitate to try therapies before they’re

supported by research.

Kristin Englund, who oversees more than 2,000

long Covid patients at the Cleveland Clinic, said a bunch of one-patient

experiments could muddy the waters for research. She said she encouraged her

team to stick with “evidence-based medicine.”

“I’d rather not be just kind of one-off trying things with

people, because we really do need to get more data and evidence-based data,”

she said. “We need to try to put things in some sort of a protocol moving

forward.”

It’s not that she lacks urgency. Englund experienced her own

long Covid symptoms. She felt terrible for months after getting sick in 2020,

“literally taking naps on the floor of my office in the afternoon,” she said.

More than anything, she said, these long Covid clinics need to

validate patients’ experiences with their illness and give them hope. She tries

to stick with proven therapies.

For example, some patients with long Covid develop POTS — a syndrome that causes

them to get dizzy and their heart to race when they stand up. Englund knows how

to treat those symptoms. With other patients, it’s not as straightforward. Her

long Covid clinic focuses on diet, sleep, meditation, and slowly increasing

activity.

But other doctors are willing to throw all sorts of treatments

at the wall to see what might stick.

At the Lucas house in Tennessee, the kitchen counter can barely

contain the pill bottles of supplements and prescriptions. One is a drug for

memory. “We discovered his memory was worse [after taking it],” Cinde said.

Other treatments, however, seemed to have helped. Cinde asked

their doctor about her husband possibly taking testosterone to boost his

energy, and, after doing research, the doctor agreed to give it a shot.

“People like myself are getting a little bit out over my skis,

looking for things that I can try,” said Stephen Heyman, a pulmonologist who treats

Rick Lucas at the long Covid clinic at Ascension Saint Thomas in Nashville.

He’s trying medications seen as promising in treating addiction and combinations of

drugs used for cholesterol and blood clots. And he has

considered becoming a bit of a guinea pig himself.

Heyman has been up and down with his own long Covid. At one

point, he thought he was past the memory lapses and breathing trouble, then he

caught the virus a second time and feels more fatigued than ever.

“I don’t think I can wait for somebody to tell me what I need to do,” he said. “I’m going to have to use my expertise to try and find out why I don’t feel well.”

Blake Farmer covers health care for Nashville Public Radio.

This story is from a reporting partnership that includes WPLN, NPR, and

KHN.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.