1990s law designed to build natural area preserves instead created a mystery

By Frank Carini / ecoRI News staff

Three decades ago the Rhode Island General Assembly passed the Natural Areas Protection Act of 1993, to provide, among other things, the “highest level of protection to the state’s most environmentally sensitive natural areas.”

Late last year, Warwick resident Nathan Cornell, co-founder and

president of the Rhode Island Old Growth Tree Society,

began looking into the 30-year-old legislation. He found a mystery.

“I made a public records request for information on the

Natural Area Preserves which was denied because the DEM apparently did not have

any information on it,” Cornell wrote in a Dec. 5 email to ecoRI News. “It appears

now that the Natural Area Preserve system was never created in Rhode Island.”

The Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) has never designated even one Natural Area Preserve. In fact, “No one currently at DEM recalls the genesis of this Act,” according to Jay Wegimont, the agency’s public affairs officer.

The legislation was supposed to elevate “the health and welfare of the people of Rhode Island by promoting the preservation of areas of unique natural interest for scientific, educational, recreational, cultural, and scenic purposes” and to “allow significant public and privately owned lands of critical environmental concern to be designated as natural area preserves.”

The law called for the DEM director to establish a system of

preserves and ensure these areas are maintained in as natural and wild a state

as is consistent with educational, scientific, biological, geological,

paleontological, and scenic purposes. The director may also adopt regulations

for establishing and managing the natural area preserve system, including

procedures for the adoption and revision of a management plan for each

designated preserve.

Cornell also reached out to the Rhode Island Natural History Survey,

which took over the state’s Natural Heritage Program in 2007 — the longtime biodiversity program a

victim of DEM budget cuts and a shift to making state-protected open space more

recreational friendly.

“The Natural History Survey had to do a lot of digging to find

anything that might be the areas that were supposed to be Natural Area

Preserves,” Cornell wrote in that early December email.

Cornell said the Survey found a list of areas from the 1990s that

were under consideration to be designated as Natural Area Preserves, including

21 locations in Gloucester, 16 in West Greenwich, 14 in Foster, 10 in Coventry,

and six in Cumberland. He said some of the locations on that list have since

been developed.

He recently told ecoRI News creating a Natural Area Preserves

system for Rhode Island would be a “great resource” to help keep important

ecosystems in their natural state and protect rare and endangered species, both

plant and animal. He also called it a solution for protecting the state’s

pockets of old-growth forests, which support many of the state’s rare and

endangered species.

The University of Rhode Island graduate pointed to Virginia,

which helped jump-start the creation of Natural Heritage programs throughout

the country, as a model for Rhode Island when it comes to creating a Natural

Area Preserve system.

Virginia has 66 Natural Area Preserves totaling

60,289 acres. Most of the state’s preserves are owned by the Virginia

Department of Conservation and Recreation, but some are lands owned by other

state and local government agencies, universities, private individuals, and

conservation organizations.

Since the creation of a Natural Area Preserve system could start

anytime, the Old Growth Tree Society has made an official request to DEM that

six areas be designated as preserves. These sites

include old-growth forests and areas with unique ecological

characteristics, according to Cornell.

Cornell said DEM director Terry Gray responded, via email,

thanking the organization for “bringing the matter to his attention and said

the whole process of designating natural area preserves was new to him and he

was going to look into it.”

Gray also told Cornell that he has tasked DEM staff to outline

how a Natural Area Preserve system would work and to look into the potential

benefits of creating one.

“This is a new process for me so I’ve asked staff to not only

outline how it works but also to look [at] the benefits of what you have

requested,” Gray wrote in a late-November email. “Some preliminary feedback I

received is that a lot of those properties are already protected … but I

haven’t gone through everything yet.”

Wegimont noted the newly created Rhode Island Forest Conservation

Commission, formed under the Rhode Island Forest Conservation Act,

is charged with developing the criteria necessary for defining the state’s most

important forestland. He said these important forestlands and characteristics

may be used in future determinations for land conservation.

“Once this happens, we will have a more modern and scientific

basis to determine if an area within RI should be designated as a Natural Area

Preserve,” he wrote in a recent email to ecoRI News. “With that said, the Forest

Conservation Commission is not charged with directly designating Natural Area

Preserves and would not have the authority to do so without amendment to that

law but their work would be hugely beneficial in any designations proposed

under the older law.”

Cornell noted management areas and state forests can and are

timber harvested.

“For example, the Great Swamp is a management area … that means

they’re logging there,” he said. “And there’s areas in the Great Swamp that

should not be logged, because there’s rare and endangered species in certain

areas. There’s old-growth forest in there. The whole thing is not old-growth

forest, but there are pockets of old-growth and they should not be a management

area. We need to protect those areas in their natural state because they’re

beautiful.”

Here is a look at the six sites the Old Growth Tree Society has

recommended as preserves (the forests in any location designated a Natural Area

Preserve must be left alone and any clear-cutting, timber harvesting, or tree

planting would be prohibited):

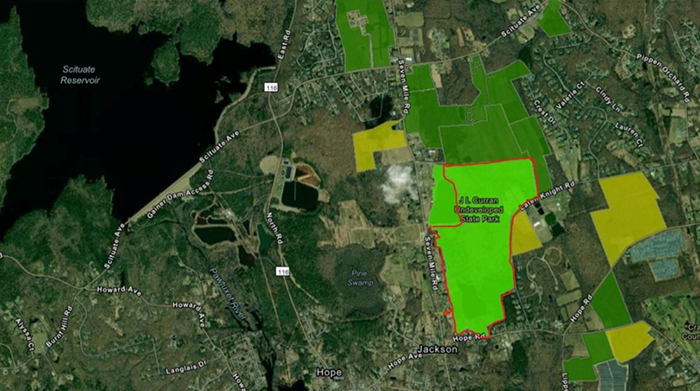

John L. Curran State Park (Cranston)

Owner: DEM.

Reason for designation: The 300-acre park contains mature

forest with a large diversity of native tree species, including American beech,

yellow birch, white ash, hickory, black tupelo, red oak, white oak, black oak,

and sassafras, with native understory trees such as American hornbeam, American

hophornbeam, and witch hazel. The park contains one of the largest intact

American beech forests in Rhode Island, and an old-growth eastern white pine

forest. There’s an American beech tree more than 8 feet in circumference, which

is likely 200-plus years old.

The Pawtuxet River American Beech Forest (Warwick)

Owner: Rhode Island Department of Transportation.

Reason for designation: The 18-acre site contains a mature

American beech forest, with the largest trees reaching about 8 feet in

circumference. There are red oaks in this forest up to 11 feet in circumference

and close to 100 feet tall. The site is an emerging old-growth forest with a

rich diversity of native tree species, including swamp white oaks, red maples,

and black birch, with a native understory of mountain laurel.

Old Growth Forests in the Great Swamp Management Area (South Kingstown)

Owner: State of Rhode Island.

Reason for designation: In this 350-acre area, there are

pockets of old-growth forest, with the older trees believed to be 200 to 300

years old. While the entire area is not old-growth, it includes much needed

buffer areas to protect those areas. The vast majority of the Great Swamp is

not old-growth, as it was likely logged in the mid-1800s to early 1900s. The

area features red and white oaks, black tupelos, American beech, and yellow

birch. The understory contains mountain laurel, and there are no invasives

present in the heart of the old-growth pockets.

Dawley Farm Forest (Warwick)

Owner: City of Warwick.

Reason for designation: This 63-acre site is a mature

forest with pockets of emerging old-growth forest. There is large yellow birch

and pignut hickory, an unusual combination in Rhode Island. There is also a

wide diversity of native tree species, including mature American beech, red

oak, white oak, black oak, sassafras, red maple, red cedar, pitch pine, and

American sycamore. While not a primary old-growth forest with a history of

farming, this forest regenerated in the 1800s with numerous trees core dated to

be more than 100 years old. Some of the older trees in the forest have been

core dated to predate the Civil War.

In December, the Warwick City Council voted to protect the

property by public trust, the first city parcel so preserved under a 2021 state

law.

CCRI/ Kent County Old Growth Forest (Warwick)

Owner: State of Rhode Island State Colleges Board of

Trustees and Kent County Memorial Hospital.

Reason for designation: This 6-acre site contains a

rich diversity of native species, including mature American beech, yellow

birch, white oak, red oak, sassafras, and American sycamore, with an understory

of American hornbeam, American hophornbeam, witch hazel, and wild blueberries.

The trees in this forest are most likely between 200 and 300 years old.

URI North Woods (South Kingstown)

Owner: State of Rhode Island, Board of Governors for Higher

Education, Office of Chief Legal Counsel.

Reason for designation: This 254-acre site contains a

diversity of native tree species, including ash and yellow birch. The area also

contains an American hornbeam forest, which is rare in Rhode Island. Currently,

students and professors at the University of Rhode Island use the forest for

research, including soil studies and species identification.

Cornell noted that the key aspect of the Natural Heritage

Program, when the state adequately funded and supported it, was to find,

monitor, and protect biodiversity. The creation of Natural Area Preserves, he

said, would help accomplish that largely abandoned mission.

“While identifying rare species is important, without a means to

protect them, there is no guaranteeing their survival,” Cornell said. “Natural

Area Preserves would protect our rarest ecosystems, including old-growth

forests.”

The nonprofit Cornell co-founded aims to locate, document, and

advocate for the preservation of all remaining old-growth trees and forests in

Rhode Island.

The organization’s work could help the Ocean State address

biodiversity loss and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. A report published in

September confirmed the “outsized role” the country’s older forests play in

storing carbon while also supporting high levels of biodiversity.

Using processed satellite images to identify structural measures

related to forest maturity, scientists found that older forests make up nearly

170 million acres (36%) of all forests in the contiguous United States. While older

forests in National parks are fully protected, only 24% of National forests and

Bureau of Land Management lands that contain older forests have similar

protections.

The study identified 50 million acres of older federal forests

as at-risk from logging, which, if cut down, would emit the equivalent of 9% of

U.S. annual greenhouse gases.

A Natural Area Preserve system, Cornell said, would promote

research and protect “interesting ecosystems.”

Anyone interested in joining the Rhode Island Old Growth Tree Society,

can contact Cornell at ncornell.ogts@gmail.com.