New Research Reveals Why You Shouldn’t Let Your Cat Outside

By UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND

|

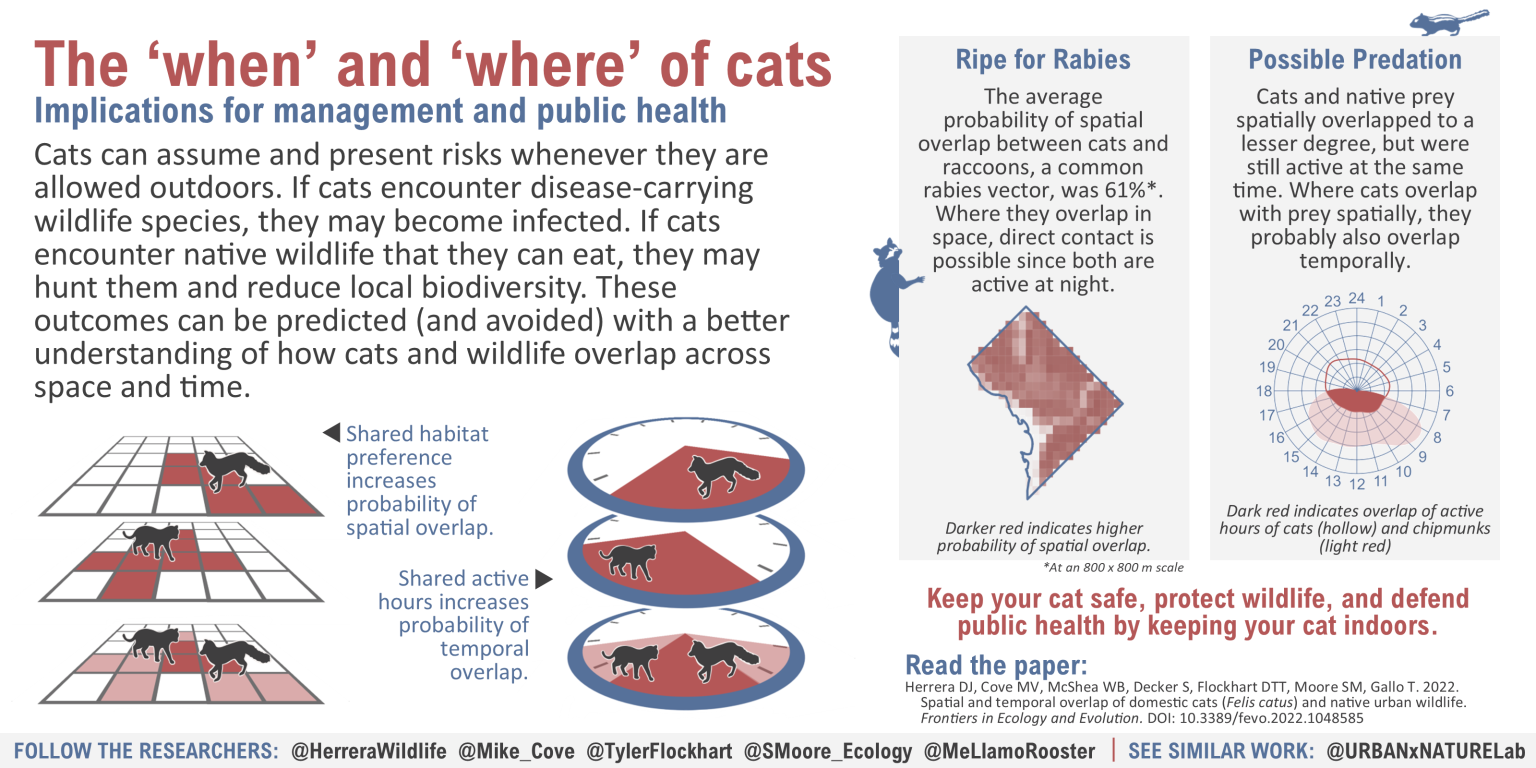

| An infographic describing the research. Credit: Daniel Herrera |

The next

time you let your cat outside for its daily adventure, you may want to

reconsider. A new study by University of Maryland researchers has found

that keeping cats indoors can significantly reduce the risks of transmitting

diseases and hunting wildlife, which can have a negative impact on native

animal populations and biodiversity.

The

study’s findings were based on data from the D.C. Cat Count, a Washington,

D.C.–wide survey that used 60 motion-activated wildlife cameras placed across

1,500 sampling locations. The researchers emphasized that humans bear a primary

responsibility in reducing these risks by keeping cats indoors.

The

cameras recorded what cats preyed on and demonstrated how they overlapped with

native wildlife, which helped researchers understand why cats and other

wildlife are present in some areas, but absent from others. The paper was

recently published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and

Evolution.

“We discovered that the average domestic cat in D.C. has a 61% probability of being found in the same space as raccoons — America’s most prolific rabies vector — 61% spatial overlap with red foxes, and 56% overlap with Virginia opossums, both of which can also spread rabies,” said Daniel Herrera, lead author of the study and Ph.D. student in UMD’s Department of Environmental Science and Technology (ENST). “By letting our cats outside we are significantly jeopardizing their health.”

In addition to the risk of being exposed to diseases that they can then bring indoors to the humans in their families (like rabies and toxoplasmosis), outdoor cats threaten native wildlife. The D.C. Cat Count survey demonstrated that cats that are allowed to roam outside also share the same spaces with and hunt small native wildlife, including grey squirrels, chipmunks, cottontail rabbits, groundhogs, and white-footed mice. By hunting these animals, cats can reduce biodiversity and degrade ecosystem health.

“Many

people falsely think that cats are hunting non-native populations like rats,

when in fact they prefer hunting small native species,” explained Herrera.

“Cats are keeping rats out of sight due to fear, but there really isn’t any

evidence that they are controlling the non-native rodent population. The real

concern is that they are decimating native populations that provide benefits to

the D.C. ecosystem.”

In

general, Herrera found that the presence of wildlife is associated with tree

cover and access to open water. On the other hand, the presence of cats

decreased with those natural features but increased with human population

density. He says that these associations run counter to arguments that

free-roaming cats are simply stepping into a natural role in the ecosystem by

hunting wildlife.

“These

habitat relationships suggest that the distribution of cats is largely driven

by humans, rather than natural factors,” explained Travis Gallo, assistant

professor in ENST and advisor to Herrera. “Since humans largely influence where

cats are on the landscape, humans also dictate the degree of risk these cats

encounter and the amount of harm they cause to local wildlife.”

Herrera

encourages pet owners to keep their cats indoors to avoid potential encounters

between their pets and native wildlife. His research notes that feral cats are

equally at risk of contracting diseases and causing native wildlife declines,

and they should not be allowed to roam freely where the risk of overlap with

wildlife is high – echoing previous calls for geographic restrictions on where

sanctioned cat colonies can be established or cared for.

Reference:

“Spatial and temporal overlap of domestic cats (Felis catus) and

native urban wildlife” by Daniel J. Herrera, Michael V. Cove, William J.

McShea, Sam Decker, D. T. Tyler Flockhart, Sophie M. Moore and Travis Gallo, 21

November 2022, Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution.

DOI:

10.3389/fevo.2022.1048585