How philosophers answer the question, is lying bad?

Lawrence Torcello, Rochester Institute of Technology

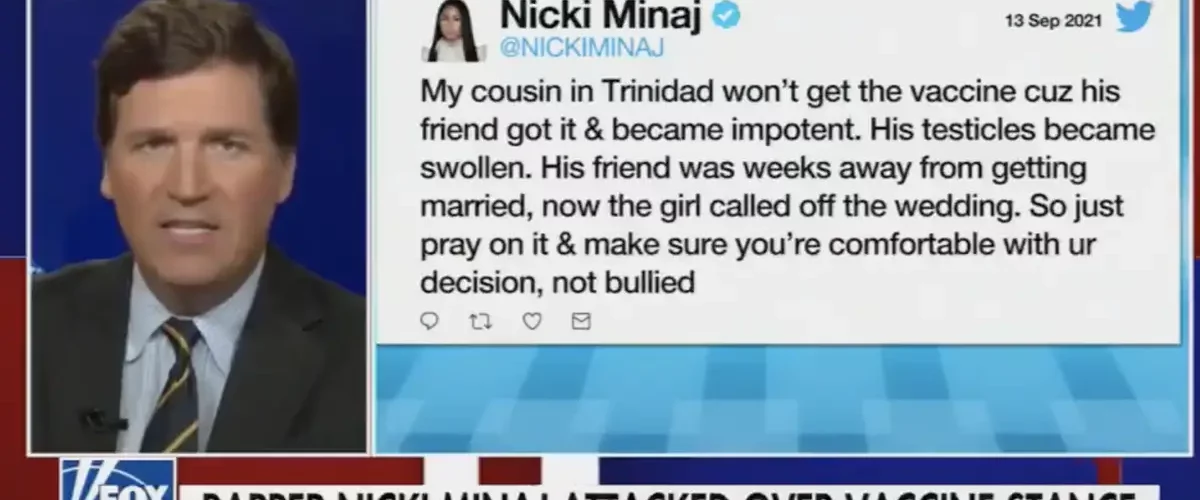

The impact of disinformation and misinformation has become impossible to ignore. Whether it is denial about climate change, conspiracy theories about elections, or misinformation about vaccines, the pervasiveness of social media has given “alternative facts” an influence previously not possible.

Bad information isn’t just a practical problem – it’s a philosophical one, too. For one thing, it’s about epistemology, the branch of philosophy that concerns itself with knowledge: how to discern truth, and what it means to “know” something, in the first place.

But what about ethics? People often think about responsibility in terms of actions and their consequences. We seldom discuss whether people are ethically accountable for not just what they do, but what they believe – and how they consume, analyze or ignore information to arrive at their beliefs.

So when someone embraces the idea that mankind has never touched the Moon, or that a mass shooting was a hoax, are they not just incorrect, but ethically wrong?

Know the good, do the good

Some thinkers have argued the answer is yes – arguments I’ve studied in my own work as an ethicist.

Even back in the 5th century B.C., Socrates linked epistemology and ethics implicitly. Socrates is mostly known through his students’ writings, such as Plato’s “Republic,” in which Plato depicts Socrates’ endeavors to uncover the nature of justice and goodness. One of the ideas attributed to Socrates is often summarized with the adage that “to know the good is to do the good.”

The idea, in part, is that everyone seeks to do what they think is best – so no one errs intentionally. To err ethically, in this view, is the result of a mistaken belief about what the good is, rather than an intent to act unjustly.

More recently, in the 19th century, British mathematician and philosopher W.K. Clifford linked the process of belief formation with ethics. In his 1877 essay “The Ethics of Belief,” Clifford made the forceful ethical claim that it is wrong – always, everywhere and for everyone – to believe something without sufficient evidence.

In his view, we all have an ethical duty to test our beliefs, to check our sources and to place more weight in scientific evidence than anecdotal hearsay. In short, we have a duty to cultivate what today might be called “epistemic humility”: the awareness that we ourselves can hold incorrect beliefs, and to act accordingly.

As a philosopher interested in disinformation and its relationship to ethics and public discourse, I think there is a lot to be gained from his essay. In my own research, I have argued that each us has a responsibility to be mindful of how we form our beliefs, insofar as we are fellow citizens with a common stake in our larger society.

Setting sail

Clifford begins his essay with the example of a ship owner who has chartered his vessel to a group of emigrants leaving Europe for the Americas. The owner has reason to doubt the boat is in a seaworthy-enough condition to cross the Atlantic, and considers having the boat thoroughly overhauled to make sure it is safe.

In the end, though, he convinces himself otherwise, suppressing and rationalizing away any doubts. He wishes the passengers well with a light heart. When the ship goes down mid-sea, and the ship’s passengers with it, he quietly collects the insurance.

Most people would probably say the ship owner was at least somewhat ethically to blame. After all, he neglected his due diligence to make sure the ship was sound before its voyage.

What if the ship had been fit for voyage and made the trip safely? It would be no credit to the owner, Clifford argues, because he had no right to believe it was safe: He’d chosen not to learn whether it was seaworthy.

In other words, it’s not only the owner’s actions – or lack of action – that have ethical implications. His beliefs do, too.

In this example it is easy to see how belief guides actions. Part of Clifford’s larger point, however, is that a person’s beliefs always hold the potential to affect others and their actions.

No man – or idea – is an island

There are two premises that can be found in Clifford’s essay.

The first is that each belief creates the cognitive conditions for related beliefs to follow. In other words, once you hold one belief, it becomes easier to believe in similar ideas.

This is borne out in contemporary cognitive science research. For example, a number of false conspiratorial beliefs – like the belief that NASA faked the Apollo Moon landings – are found to correspond with the likelihood of a person falsely believing that climate change is a hoax.

Clifford’s second premise is that no human beings are so isolated that their beliefs won’t at some point influence other people.

People do not arrive at their beliefs in a vacuum. The influence of family, friends, social circles, media and political leaders on others’ views is well documented. Studies show that mere exposure to misinformation can have a lasting cognitive impact on how we interpret and remember events, even after the information has been corrected. In other words, once accepted, misinformation creates a bias that resists revision.

Taking these points together, Clifford argues that it is always wrong – not just factually, but ethically – to believe something on insufficient evidence. This point does not assume that each person always has the resources to develop an informed belief on each topic. He argues it is acceptable to defer to experts if they exist, or withhold judgment on matters where one has no sound grounding for an informed belief.

That said, as Clifford suggests in his essay, theft is still harmful, even if the thief has never been exposed to the lesson that it is wrong.

An ounce of prevention

Arguing that people are ethically responsible for nonevidential beliefs doesn’t necessarily mean they are blameworthy. As I have argued in other work, Clifford’s premises show the morally relevant nature of belief formation.

It is enough to suggest that developing and nurturing critical thinking is an ethical responsibility, without denouncing every person who holds a belief that can’t be supported as inherently immoral.

Ethics is often talked about as if it were merely a matter of identifying and chastising bad behaviors. Yet, as far back as Plato and Socrates, ethics has been about offering guidance for a life well lived in community with others.

Likewise, the ethics of belief can serve as a reminder of how important it is, for other people’s sakes, to develop good habits of inquiry. Learning to identify fallacious arguments can be a kind of cognitive inoculation against misinformation.

That might mean renewing educational institutions’ investment in disciplines that, like philosophy, have historically taught students how to think critically and communicate clearly. Modern society tends to look for technological mechanisms to guard us against misinformation, but the best solution might still be a solid education with generous exposure to the liberal arts – and ensuring all citizens have access to it.![]()

Lawrence Torcello, Associate Professor of Philosophy, Rochester Institute of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.