How the Last 12,000 Years Have Shaped What Humans Are Today

By OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY

Humans have been evolving for millions of years.

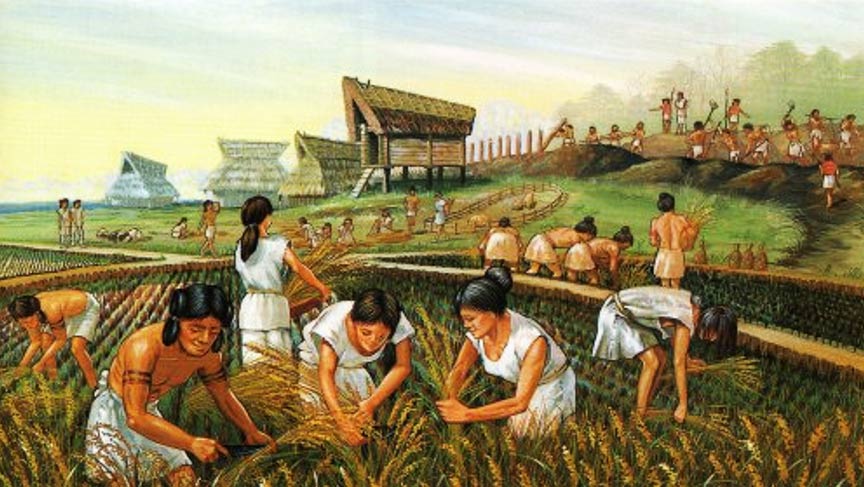

However,

the past 12,000 years have been the most dynamic and impactful for human

living. According to Clark Spencer Larsen, a professor of anthropology at The Ohio State University, our modern world all started

with the advent of agriculture

“The

shift from foraging to farming changed everything,” Larsen said.

Along

with food crops, humans also planted the seeds for many of the most vexing

problems of modern society.

“Although

the changes brought about by agriculture brought plenty of good for us, it also

led to increasing conflict and violence, rising levels of infectious diseases,

reduced physical activity, a more limited diet, and more competition for

resources,” he said.

Larsen is the organizer and editor of a Special Feature recently published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. He is also the author of the introduction to the section, titled “The past 12,000 years of behavior, adaptation, population, and evolution shaped who we are today.”

The

Special Feature includes eight articles based mostly on bioarchaeology – the

study of human remains and what they can tell scientists about changes in diet,

behavior, and lifestyle over the last 10 millennia or so. Larsen is the

co-author on two of these eight articles.

One

message that connects all the articles is that the major societal issues of

today have ancient roots, he said.

“We

didn’t get to where we are now by happenstance. The problems we have today with

warfare, inequality, disease, and poor diets, all resulted from the changes

that occurred when agriculture started,” Larsen said.

The

shift from foraging to farming led humans, who had led a mostly transitory

life, to create settlements and live a much more sedentary existence.

“That

has had profound implications for virtually every aspect of our lives back

then, now, and going forward,” he said.

Growing

food allowed the world population to grow from about 10 million in the later

Pleistocene Epoch to more than 8 billion people today.

But

it came at a cost. The varied diet of foragers was replaced with a much more

limited diet of domesticated plants and animals, which often had reduced

nutritional quality. Now, much of the world’s population relies on three foods

– rice, wheat, and corn – especially in areas that have limited access to

animal sources of protein, Larsen said.

Another

important change in the diet of humans was the addition of dairy. In one

article in the Special Feature, researchers examined dental calculus found in remains

to show the earliest evidence of milk consumption dates to about 5,000 years

ago in northern Europe.

“This

is evidence of humans adapting genetically to be able to consume cheese and

milk, and it happened very recently in human evolution,” he said. “It shows how

humans are adapting biologically to our new lifestyle.”

As

people began creating agricultural communities, social changes were occurring

as well. Larsen co-authored one article that analyzed strontium and oxygen

isotopes from tooth enamel of early farming communities from more than 7,000

years ago to help determine where residents were from. Results showed that

Çatalhöyük, in modern Turkey, was the only one of several communities studied

where nonlocals apparently lived.

“This

was laying the foundation for kinship and community organization in later

societies of western Asia,” he said.

These

early communities also faced the problem of many people living in relatively

cramped areas, leading to conflict.

In

one article, researchers studying human remains in early farming communities

across western and central Europe found that about 10% died from traumatic

injuries.

“Their

analysis reveals that violence in Neolithic Europe was endemic and scaling

upward, resulting in patterns of warfare leading to increasing numbers of

deaths,” Larsen writes in the introduction.

Research

reported in this PNAS issue also reveals how these first human communities

created the ideal conditions for another problem that is top-of-mind in the

world today: infectious disease. Raising farm animals led to the common

zoonotic diseases that can be transmitted from animals to people, Larsen said.

While

the climate change crisis of today is unique in human history, past societies

have had to deal with more short-term climate disasters, particularly long

droughts.

In

a perspective article co-authored by Larsen, the researchers noted that

economic inequality, racism, and other types of discrimination have been key

factors in how societies have fared under these climate emergencies, and these

factors will play a role in our current crisis.

Those

communities with more inequality were most likely to experience violence in the

wake of climate disasters, Larsen said.

What

may be most surprising about all the changes documented in the Special Feature

is how quickly they all occurred, he said.

“When

you look at the 6 or so million years of human evolution, this transition from

foraging to farming and all the impact it has had on us – it all happened in

just a blink of an eye,” Larsen said.

“In

the scale of a human lifespan, it may seem like a long time, but it really is

not.”

The

research presented in the Special Feature also shows the amazing ability of

humans to adjust to their surroundings.

“We

are remarkably resilient creatures, as the last 12,000 years have shown,” he

said.

“That

gives me hope for the future. We will continue to adapt, to find ways to face

challenges, and to find ways to succeed. That is what we do as humans.”

Reference:

“The past 12,000 years of behavior, adaptation, population, and evolution

shaped who we are today” by Clark Spencer Larsen, 17 January 2023, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DOI:

10.1073/pnas.2209613120