Cleaning PFAS out of our water

University of British Columbia

Engineers

at the University of British Columbia have developed a new water treatment that

removes "forever chemicals" from drinking water safely, efficiently

-- and for good.

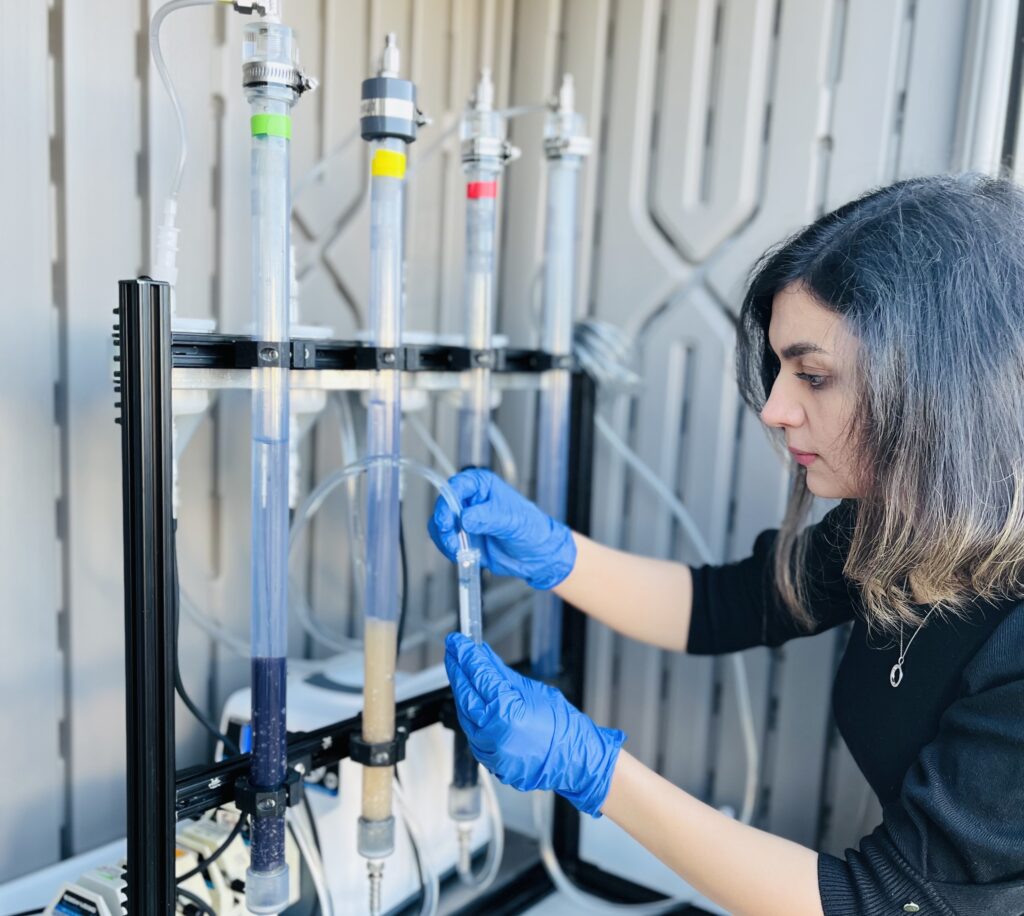

Fatemeh Asadi Zeidabadi, a PhD student in the UBC department

of chemical and biological engineering and a student

in Dr. Madjid Mohseni's group. Photo credit: Mohseni lab

Forever chemicals, formally known as PFAS (per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances) are a large group of substances that make certain products non-stick or stain-resistant.

There are more than 4,700 PFAS in use, mostly in raingear,

non-stick cookware, stain repellents and firefighting foam. Research links

these chemicals to a wide range of health problems including hormonal

disruption, cardiovascular disease, developmental delays and cancer.

To remove

PFAS from drinking water, Dr. Mohseni and his team devised a unique adsorbing

material that is capable of trapping and holding all the PFAS present in the

water supply.

The PFAS

are then destroyed using special electrochemical and photochemical techniques,

also developed at the Mohseni lab and described in part in a new paper

published recently in Chemosphere.

While there are treatments currently on the market, like activated carbon and ion-exchange systems which are widely used in homes and industry, they do not effectively capture all the different PFAS, or they require longer treatment time, Dr. Mohseni explained.

"Our

adsorbing media captures up to 99 per cent of PFAS particles and can also be

regenerated and potentially reused. This means that when we scrub off the PFAS

from these materials, we do not end up with more highly toxic solid waste that

will be another major environmental challenge."

He

explained that while PFAS are no longer manufactured in Canada, they are still

incorporated in many consumer products and can then leach into the environment.

For example, when we apply stain-resistant or repellent sprays/materials, wash

PFAS-treated raingear, or use certain foams to put down fires, the chemicals

end up in our waterways. Or when we use PFAS-containing cosmetics and

sunscreens, the chemicals could find their way into the body.

For most

people, exposure is through food and consumer products, but they can also be

exposed from drinking water -- particularly if they live in areas with

contaminated water sources.

Dr.

Mohseni, whose research group also focuses on developing water solutions for

rural, remote and Indigenous communities, noted: "Our adsorbing media are

particularly beneficial for people living in smaller communities who lack

resources to implement the most advanced and expensive solutions that could

capture PFAS. These can also be used in the form of decentralized and in-home

water treatments."

The UBC

team is preparing to pilot the new technology at a number of locations in B.C.

starting this month.

"The results we obtain from these real-world field studies will allow us to further optimize the technology and have it ready as products that municipalities, industry and individuals can use to eliminate PFAS in their water," said Dr. Mohseni.