Supreme Court Hears Oral Arguments in Chariho School Committee Case

By Cynthia Drummond for the Beaver River Valley Community Association (BRVCA)

Oral arguments were presented Thursday before the Rhode Island Supreme Court in

the case of Richmond School Committee candidate Jessica Purcell, who is

challenging the Richmond Town Council, Clay Johnson and the Chariho School

Committee over the council’s appointment of Johnson to fill a vacancy on the

school committee.

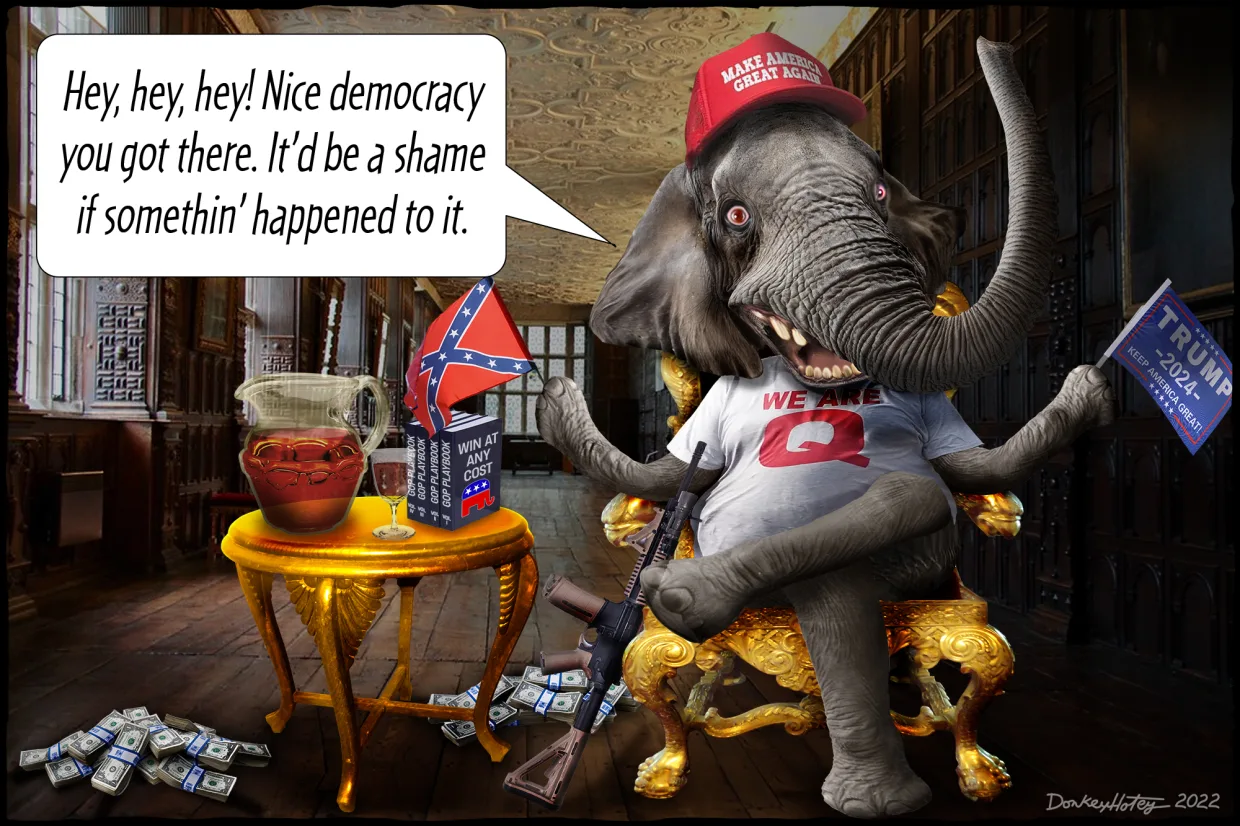

Photo credit: DonkeyHotey / WhoWhatWhy (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Purcell,

a Democrat who came third in the Nov. 8, 2022 election, lost her bid for a

School Committee seat by just 27 votes. When Richmond committee member

Gary Liguori announced in January, 2023 that he was moving out of Rhode Island

and vacating his seat, it was believed that under the provisions of the

town’s Home Rule charter,

Purcell, with the next-highest number of votes, would be named to fill the

seat.

But

on Jan. 19, three of the five members of the Richmond Town Council appointed

Republican political operative Clay Johnson to the vacant seat.

Purcell

hired attorney Jeffrey Levy and took her case to the Supreme Court.

Named

as defendants and represented by attorney Joseph Larisa are Johnson, the

Richmond Town Council and the Chariho School Committee.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Joe Larisa is a hard-line MAGA conservative who has been employed by the Town of Charlestown as "Special Solicitor for Indian Affairs." In that role, Larisa monitors the Narragansett Indian Tribe and then acts to block any measure or effort that might improve the economic or social conditions of the Tribe. Tribal leaders have frequently called him racist. - Will Collette.

Several

Johnson supporters were in the court room, including Town Council members

Michael Colasante and Helen Sheehan, both of whom voted to name Johnson to the

School Committee.

Also

present were Chariho School Committee attorney Jon Anderson and attorney Mark

Reynolds, the current Richmond Town Moderator.

Anderson

said he had been instructed by the committee not to comment on the case.

“The School Committee voted for me to take no position,” he said.

The

arguments

Each attorney had 20 minutes to present his case and an additional 10 minutes each for rebuttals. Levy presented his arguments to the five Justices, Chief Justice Paul Suttell and Justices Maureen McKenna Goldberg, William Robinson III, Erin Lynch Prata and Melissa Long.

At

issue is whether the town charter or the Chariho Act takes

precedence. The three council members who voted to appoint Johnson, who did not

run for election, over Purcell, who received 1,469 votes, defended their

decision on the grounds that the Chariho Act, state legislation passed in 1958

governing the Chariho Regional School District, took precedence over the

Richmond Home Rule Charter, which was approved by voters in 2008 and ratified

by the state legislature.

The

charter states that in the case of a vacancy on the 12-member Chariho School

Committee, the person who received the next-highest number of votes should be

named to fill the seat – in this case, Purcell.

Levy’s

argument is based on the compatibility of the Chariho Act and the town charter,

because the act requires the Town Council to fill a vacant School Committee

seat and the charter states that the person chosen by the council should be the

next-highest vote-getter.

Justice

Lynch Prata posed a question that lies at the heart of the case.

“Is

that what the voters of Richmond intended, in terms of having the next

vote-getter win, and if that’s what they intended, did the General Assembly

ratify that piece?” she asked Levy. “Because I don’t think that anybody’s

trying to say that you were intending to repeal the Chariho Act.”

Levy

replied that harmonizing the Chariho Act and the town charter would eliminate

the need for the specific ratification of certain provisions.

“This

court’s analysis, to me, seems to be that it’s possible to comply with both

laws here,” he said. “It’s possible to comply with the Chariho Act in that the

council appoints the replacement, and it’s possible to comply with the charter

if the council appoints the runner-up from the last election.”

Goldberg,

who was critical throughout Levy’s argument, said she believed that Richmond

voters wanted the Chariho Act to prevail in cases where the act and the charter

were incompatible.

“You

have a provision in the Chariho Act that dictates how vacancies on that board

are to be filled, period,” she said.

Levy

countered that the town charter was not inconsistent with the Chariho Act.

“The

charter provision is not inconsistent with the Chariho Act. It is consistent

with the Chariho Act,” he said.

“No,

it’s not,” Goldberg replied.

The

justices questioned Levy’s assertion that when the General Assembly approved

the town charter, it was, in effect, ratifying it in its entirety.

Justice

Lynch-Prata asked what would be necessary for the state to specifically

validate the town charter.

“What’s

required for express validation?” she asked.

Levy

replied that the General Assembly had ratified the entire charter, making

further ratification unnecessary.

“The

General Assembly ratified the entire charter in all respects which require

ratification,” he said.

Goldberg

pointed out that the Chariho Act applies not only to Richmond to all three

Chariho towns, including Charlestown and Hopkinton.

“We

have a charter and we have a state law that doesn’t just apply to Richmond,”

she said. “It’s three towns, and it specifically says how vacancies are to be

filled.”

Levy

concluded his argument by alluding to the politics motivating the three

Republican council members to name fellow Republican Johnson to the School

Committee.

“There’s

a political motivation here, but that’s beside the point,” he said. “The point

is…”

Goldberg

broke in,

“There’s more than a political motivation,” she said. “This is not a happy marriage over at Chariho, but that is not before us, happily.”

Larisa’s arguments

Central

to Larisa’s arguments is the assertion that the Chariho Act and the town

charter cannot, as Levy had argued, be harmonized because they are

fundamentally incompatible.

“Why

is it not?” Justice Robinson asked. “Why don’t the canons [ordinances] apply if

they’re both actions of the General Assembly? ... Taking the two actions of the

General Assembly, the Chariho Act and the charter, which it ratified, why doesn’t

the charter control this issue, because it’s so specific, and because it’s

later in time?”

Larisa

responded that the General Assembly had never ratified the charter provision in

question. He also cited case law showing the diverse ratification mechanisms

employed by the General Assembly.

“As

this court knows, a home rule charter community has certain rights in areas of

local concern. It has no rights for ordinance and charter in areas of statewide

concern,” he said.

Robinson

questioned Larisa’s assertion that state law trumped the town charter.

“Where

has that ever been said?” he asked.

“It

was ratified,” Robinson continued, referring to the town charter, “so

therefore, it becomes state law for Richmond. It’s an act of the General

Assembly.”

Larisa

said that the General Assembly had to specifically ratify the provision of the

charter in order for that provision to be state law.

“The

way a charter, or a provision of a charter, becomes state law is express

ratification of the provision…saying all laws are repealed,” he said. “Without

the ‘all laws are repealed’ in consistent … language or without express

ratification… the provision at issue, the Chariho Act’s vacancy – filling

provision, has simply never been repealed by the General Assembly and since

it’s an inferior charter provision, or ordinance, it succumbed to the Chariho

Act.”

(It

should be noted that it would not be legally possible for Richmond to

unilaterally repeal any provisions of the Chariho Act, since any and all

amendments to the act require the consent of all three towns.)

Robinson

also took issue with Larisa’s description of the charter as inferior.

“What do you mean an inferior charter provision,” he said. “The charter commission worked hard to come up with the charter. They went to Providence, to the General Assembly, and they passed it. It’s not inferior. It’s later in time, more specific, and, frankly, superior.”

Outside

the Licht Judicial Complex after the arguments had concluded, Levy repeated his

assertions that the charter and the Chariho Act are compatible and the charter

had become state law when it was ratified by the General Assembly.

Levy

also repeated that no part of the Chariho Act could, as Larisa suggested, be

repealed because all three towns must agree on amendments.

“You

can’t repeal the Chariho Act provisions, because then you would be leaving

Charlestown and Hopkinton hanging without a way to replace, or fill vacancies,”

he said. “So, the fact that there was no repeal is irrelevant here, from my

perspective.”

Purcell,

who was in the court room, said the legal arguments differed from her

perception of her case.

“A

lot of words, a lot of analyzing that is much different from the way I look at

it and the way I think most people I speak to look at it,” she said. “I think

it was very simple and clear what the Town Council should have done from the

start and it’s unfortunate we’ve had to go through this many months of

additional analyzing and back-and-forth and legal fees, honestly. So, I’m not

sure how the judges will decide. They seemed sort of split about what they felt

was the best way to interpret the conflict or the lack of conflict or what

takes precedence, so I’m really not sure what’s going to happen.”

Johnson

and Larisa did not speak to reporters after the proceeding.

The

court is expected to issue its decision in the coming weeks.