But labels should be designed for higher visibility, researchers suggest

University of California - Davis

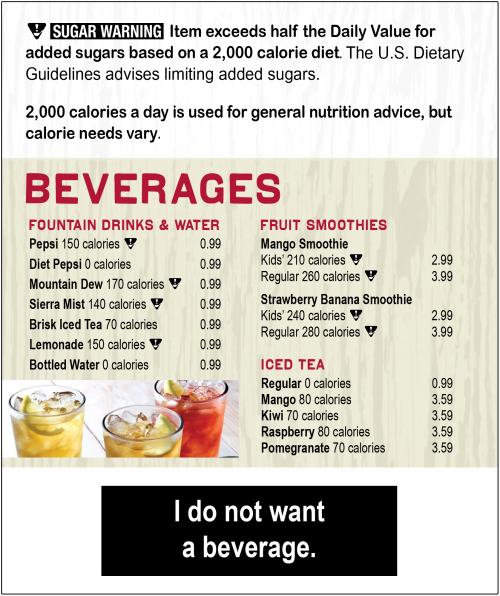

Example of a simulated label used in the study.

Added-sugar warning labels reduced the likelihood that consumers would order items containing high amounts of added sugar in an online experiment led by University of California, Davis, researchers.

Menu labels can help inform consumers about the surprisingly high amount of added sugar in even the smallest sizes of soda or in unexpected items like salad dressings and sauces.

In a randomized controlled trial, researchers found that warning labels reduced the probability of ordering a high-added-sugar item by 2.2%.

However, only 21% of the consumers exposed to the added-sugar warning labels noticed them. Among those who noticed the labels, there was a reduction of 4.9 grams of added sugar ordered, compared to the control group.

"Given the frequency of restaurant food consumption, these modest effects could lead to meaningful changes in sugar intake at the population level, and the labels should motivate restaurants to reduce the added-sugar content of their menus," said Jennifer Falbe, a researcher in the Department of Human Ecology and lead author. Notably, it is estimated that 21% of calories consumed in the United States come from restaurants.

However,

given that most participants did not notice the added-sugar labels, Falbe

added, "our findings also indicate that menu labels should be designed for

higher visibility."

First look at behavioral outcomes

The

study, published online this week in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, looked

at people's behavior as they simulated ordering from menus for fast-food and

full-service chain restaurants. Co-authors include researchers from other

universities and the Center for Science in the Public Interest.

Falbe said this study is the first to test a restaurant menu

added-sugar warning label on behavioral outcomes. In the study, consumers

selected menu items they would want to order for dinner from online menus that

included common foods like hamburgers, salads, French fries, beverages (with

sugar and sugar-free), sodas, cookies, sundaes and smoothies.

More

than 15,000 participants were recruited to match the U.S. population in terms

of age, gender, race and ethnicity, and education. Half of them were randomized

to select from online menus with added-sugar warning labels while the other

half selected from menus without added-sugar labels (the control group). In the

intervention group, warning labels had been added to items containing over 50%

of the recommended daily limit for added sugar. Researchers were able to record

all participants' behavior as they simulated ordering dinner from those menus

in 2021.

Major

findings include:

- Added-sugar warning labels reduced the likelihood that consumers would order an item high in added sugar.

- The warning labels helped consumers understand whether menu items were high in added sugar.

- A large majority, or 72%, of consumers in the study indicated that they supported a law requiring chain restaurants to post these warning labels on their menus.

Falbe

and colleagues had conducted previous studies on developing such warning

labels, including one that designed added-sugar menu labels based on the design

of existing sodium warning labels present on menus in New York and

Philadelphia.

While

the United States Food and Drug Administration requires large chain restaurants

to make some nutrition information available in restaurants, there is currently

no requirement for added sugar to be publicly disclosed for restaurant foods,

researchers said.

"This

gap in information leaves consumers in the dark about how much added sugar is

contained in the foods and drinks that they consume," said DeAnna Nara, a

senior policy associate at Center for Science in the Public Interest and

co-author. "We know that chain restaurants serve up foods and beverages

packed with added sugars and are especially hard places for consumers to

navigate and make healthy choices for themselves and their families, especially

those managing chronic diseases."

"Warning

icons provide easily interpretable information to consumers and equip them with

the information they need to make informed decisions," said Nara.

"They also have the potential to encourage restaurants to rethink their

recipes, spurring reformulation to cut back on added sugars."

Co-authors

of the study include researchers from UC Davis, Harvard T.H. Chan School of

Public Health, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania,

Center for Science in the Public Interest in Washington D.C., and the

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Funding was provided by Bloomberg Philanthropies to CSPI. Bloomberg Philanthropies and CSPI played no role in the data collection, experimental design or analysis of the data. Researchers were also supported by career development and training grants from the NIH.