What’s Best for Heart-Healthy Eating – And What Misses the Mark

American Heart Association

The American Heart Association’s new scientific statement assesses popular diets and their alignment with heart-healthy guidelines. Top ratings were given to the DASH-style, Mediterranean, and vegetarian and pescatarian diets, while Paleo and ketogenic diets did not meet heart-healthy criteria. The statement also emphasizes the role of social determinants in shaping healthy eating patterns.

- A new American Heart Association scientific statement assesses and scores

the heart healthiness of popular dietary patterns.

- Several

dietary patterns, including the DASH-style eating plan, Mediterranean,

pescatarian, and vegetarian eating patterns, received top ratings for

aligning with the Association’s dietary guidance.

- A

few eating patterns, including Paleo and ketogenic diets, contradict the

Association’s guidance and did not rank as heart-healthy eating patterns.

- The

statement suggests opportunities for dietary research and interventions to

promote health equity, recognizing the importance of social determinants

of health in shaping dietary patterns.

\Many popular dietary patterns score high for heart health; however, a few contradict the American Heart Association’s dietary guidance and did not rank as heart healthy, according to a new scientific statement published on April 27 in the Association’s flagship, peer-reviewed journal Circulation.

“The number of different, popular dietary patterns has proliferated in recent years, and the amount of misinformation about them on social media has reached critical levels,” said Christopher D. Gardner, Ph.D., FAHA, chair of the writing committee for the new scientific statement and the Rehnborg Farquhar Professor of Medicine at Stanford University in Stanford, California.

“The public — and even many health care professionals — may

rightfully be confused about heart-healthy eating, and they may feel that they

don’t have the time or the training to evaluate the different diets. We hope

this statement serves as a tool for clinicians and the public to understand

which diets promote good cardiometabolic health.”

Cardiometabolic health refers to a group of factors that affect metabolism (the body’s processes that break down nutrients in food, and build and repair tissues to maintain normal function) and the risk of heart and vascular disease.

These factors include blood glucose, cholesterol and other lipids,

blood pressure and body weight. While abnormal levels of one factor may

increase the risk for heart disease, abnormalities in more than one factor

raise the risk even more, and for more severe disease.

The statement rates how well popular dietary patterns align with the American Heart Association’s Dietary Guidance. The guidance includes ten key features of a dietary pattern to improve cardiometabolic health, which emphasizes limiting unhealthy fats and reducing the consumption of excess carbohydrates.

This balance optimizes both cardiovascular and general metabolic health, and limits the risks of other health conditions such as Type 2 diabetes and risk factors such as obesity that may result from excess consumption of carbohydrates, particularly processed carbohydrates (refined grains) and sugar sweetened beverages, which are both associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

The new scientific statement is the first to analyze how closely popular dietary patterns adhere to those features, and the guidance is focused on being adaptable to individual budgets as well as personal and cultural preferences. committee reviewed the defining features of several dietary patterns that are meant to be followed long term. Dietary patterns were grouped by similarity in key characteristics, resulting in 10 categories:

- DASH-style

— describes an eating pattern that’s like the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)

diet, emphasizing vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts and

seeds, and low-fat dairy and includes lean meats and poultry, fish and

non-tropical oils. The Nordic and Baltic diets are other types of this

eating pattern.

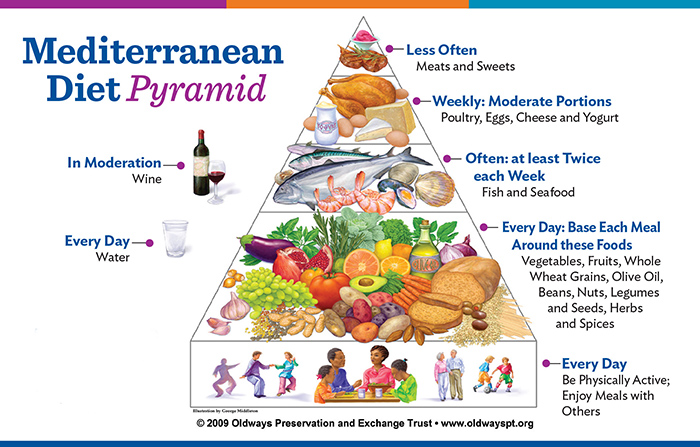

- Mediterranean-style

— also known as the Mediterranean diet, this pattern limits dairy;

emphasizes vegetables, fruit, whole grains, legumes, nuts and seeds, fatty

fish and extra virgin olive oil; and includes moderate drinking of red

wine.

- Vegetarian-style/Pescatarian

— a plant-based eating pattern that includes fish.

- Vegetarian-style/Ovo/Lacto

— plant-based eating patterns that include eggs (ovo-vegetarian), dairy

products (lacto-vegetarian) or both (ovo-lacto vegetarian).

- Vegetarian-style/Vegan

— a plant-based eating pattern that includes no animal products.

- Low-fat

— a diet that limits fat intake to less than 30% of total calories,

including the Volumetrics eating plan and the Therapeutic Lifestyle Change

(TLC) plan.

- Very

low-fat — a diet that limits fat intake to less than 10% of total

calories, including Ornish, Esselstyn, Pritikin, McDougal, Physicians

Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM) diets. Some may also be

considered vegan.

- Low-carbohydrate

— a diet that limits carbohydrates to 30-40% of total calorie intake, and

includes South Beach, Zone diet and low glycemic index diets.

- Paleolithic

— also called the Paleo diet, it excludes whole and refined grains,

legumes, oils and dairy.

- Very

low-carbohydrate/ketogenic — limits carbohydrate intake to less than 10%

of daily calories and includes Atkins, ketogenic and the Well-Formulated

Ketogenic diets.

Each diet was evaluated against 9 of the 10 features of the American Heart Association’s guidance for a heart-healthy eating pattern. The only element not used in scoring was “eating to achieve a proper energy balance to maintain a healthy weight,” since this is influenced by factors other than dietary choices, such as physical activity level, and applies equally to all the diet categories.

Defining features of the diets were given points based on how well each feature aligned with the Association’s guidance: 1 point for fully meeting, 0.75 points for mostly meeting and 0.5 points for partially meeting the guidance. If an aspect of the diet did not meet the guidance at all, zero points were given for that component.

The resulting scores were totaled and adjusted to arrive at a rating

between 0-100, with 100 indicating the closest adherence to American Heart

Association’s dietary guidance.

Of note, the statement did not review commercial dietary

programs, such as Noom or Weight Watchers; diets designed to be followed for

less than 12 weeks; dietary practices such as intermittent fasting or time-restricted eating;

or diets designed to manage non-cardiovascular conditions (such as

gastrointestinal conditions and food allergies or intolerances).

The writing group found that the dietary patterns reviewed varied widely in their alignment with American Heart Association guidance, earning scores from 31 to 100. Scores were grouped into four tiers, and aspects of the diets that help them adhere to the guidance as well as potential challenges to adherence were noted.

The only element of the guidance that was

part of every diet pattern was “minimize the intake of foods and beverages with added sugars.”

The statement also identifies opportunities to enhance the healthy aspects of

each eating pattern.

Tier 1: Highest-rated eating plans (scores higher than 85)

The four patterns with the highest rating are flexible and provide a broad array of healthy foods to choose from. The DASH-style eating pattern received a perfect score by meeting all of the Association’s guidance.

These eating patterns are low in salt, added sugar, alcohol,

tropical oils and processed foods, and rich in non-starchy vegetables, fruits,

whole grains and legumes. Protein tends to be mostly from plant sources (such

as legumes, beans or nuts), along with fish or seafood, lean poultry and meats,

and low-fat or fat-free dairy products.

The Mediterranean-style diet is

also highly rated. Since it doesn’t explicitly address added salt and includes

moderate alcohol consumption (rather than avoiding or limiting alcohol), it has

a slightly lower score than DASH. In addition, most of the features of a

vegetarian eating pattern align with AHA’s dietary guidance. Pescatarian and vegetarian eating

plans that include eggs, dairy or both were also in the top tier.

“If implemented as intended, the top-tier dietary patterns

align best with the American Heart Association’s guidance and may be adapted to

respect cultural practices, food preferences and budgets to enable people to

always eat this way, for the long term,” Gardner said.

Tier

2: Vegan and low-fat diets (scores 75-85)

Vegan and low-fat diets also emphasize eating vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes and nuts, while limiting alcohol and foods and beverages with added sugar. However, restrictions in the vegan eating pattern may make it more difficult to follow long-term or when eating out.

Following a vegan eating pattern may increase the risk of vitamin B-12 deficiency, which may cause red blood cell abnormalities leading to anemia; therefore, supplementation may be recommended by clinicians.

Low-fat diets often treat all fats equally, while the Association’s guidance suggests replacing saturated fat with healthier fats such as mono- and polyunsaturated fats. Those who follow a low-fat diet may over-consume less healthy sources of carbohydrates, such as added sugars and refined grains. However, these factors may be overcome with proper counseling and education for people interested in these eating patterns.

Tier

3: Very low-fat and low-carb (scores 55-74)

These dietary patterns have low to moderate alignment with

the Association’s guidance.

A motivator for some people to follow a very low-fat (often

vegan) diet may be that some studies have shown their potential to slow

progression of fatty artery build-up. A healthy low-carbohydrate eating pattern

has been shown to affect weight loss, blood pressure, blood sugar and

cholesterol equally when compared to a healthy low-fat diet. However, both

patterns restrict food groups that are emphasized in the Association’s

guidance.

Very low-fat diets lost points for restricting nuts and

healthy (non-tropical) plant oils. This eating pattern may also result in

deficiencies of vitamin B-12, essential fatty acids and protein, leading to

anemia and muscle weakness.

Low-carb diets restrict fruits (due to sugar content), grains and

legumes. In restricting carbohydrates, followers tend to decrease consumption

of fiber while increasing consumption of saturated fat (from meats and foods

from animal sources), both of which contradict the Association’s guidance.

The statement suggests that loosening restrictions on food

groups such as fruits, whole grains, legumes and seeds may help people stick to

a lower carbohydrate eating pattern while promoting heart health over the long

term.

Tier

4: Paleolithic and Very low-carb/Ketogenic diets (scores less than 55)

These two eating patterns, often used for weight loss, align poorly with the Association’s dietary guidance. Strengths of the very low-carb eating patterns are the emphasis on consuming non-starchy vegetables, nuts and fish, along with minimizing the consumption of alcohol and added sugar.

In studies up to 6 months long, improvements in body weight and blood sugar have been shown with these diets. However, after a year, most improvements were no different from the results of a less restrictive diet.

Restrictions on fruits, whole grains and legumes may result in reduced fiber

intake. Additionally, these diets are high in fat without limiting saturated

fat. Consuming high levels of saturated fat and low levels of fiber are both

linked to the development of cardiovascular disease.

“There really isn’t any way to follow the Tier 4 diets as intended and still be aligned with the American Heart Association’s Dietary Guidance,” Gardner said.

“They are highly restrictive and

difficult for most people to stick with long term. While there will likely be

short-term benefits and substantial weight loss, it isn’t sustainable. A diet

that’s effective at helping an individual maintain weight loss goals, from a

practical perspective, needs to be sustainable.”

Opportunities to promote equity in healthy eating

The statement suggests opportunities for dietary research

and interventions to promote health equity, recognizing the importance of

social determinants of health in shaping dietary patterns. Advocating for

changes at each of these levels supports all populations toward achieving

health equity.

- Individuals: Educational efforts should be

culturally relevant to increase their effectiveness for people from

underrepresented racial and ethnic groups. Studies that examine dietary

patterns from the various African, Asian and Latin American cultures may

prove helpful in creating the knowledge base for these types of

educational efforts.

- Relationships and social networks: Families,

friends and traditions are important influencers on eating patterns.

Programs are needed to promote relationships that support healthy eating

across diverse population groups, and particularly those that leverage the

family structure as a means of social support. One example is the American

Heart Association’s new campaign Together at the Table/Juntos En La Mesa,

designed to help Hispanic/Latino families cook and eat a heart-healthy

diet that celebrates their cultural flavors while improving their

families’ health.

- Communities: Structural racism is a

contributing factor to diet-related disease. Historically marginalized

populations should be involved in all phases of research and in the

development of programs and interventions. Diet intervention studies

should incorporate healthier versions of dietary patterns from racially

and ethnically diverse cultures.

- Policy: Policies may address

disparities in dietary patterns by race and ethnicity, dismantling unjust

historical practices that limit healthy food access. Legislation at the

local, national and global levels may provide long-term support for

healthy eating for large numbers of people and shape more equitable and

healthy societies.

In learning more about various dietary patterns and how effective they may be, Gardner notes that people may hear conflicting information from different studies of the same diet. “We often find that people don’t fully understand popular eating patterns and aren’t following them as intended.

When that is the case, it is challenging to determine

the effect of the ‘diet as intended’ and distinguish that from the ’diet as

followed.’ Two research findings that seem contradictory may merely reflect

that there was high adherence in following the diet in one study and low

adherence in the other.”

Reference: “Popular Dietary Patterns: Alignment With

American Heart Association 2021 Dietary Guidance: A Scientific Statement From

the American Heart Association” by Christopher D. Gardner, Maya K. Vadiveloo,

Kristina S. Petersen, Cheryl A.M. Anderson, Sparkle Springfield, Linda Van

Horn, Amit Khera, Cindy Lamendola, Shawyntee M. Mayo, Joshua J. Joseph and on

behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Lifestyle and

Cardiometabolic Health; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on

Hypertension; and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease, 27 April 2023, Circulation.

DOI:

10.1161/CIR.0000000000001146

Co-authors are Vice Chair Maya Vadiveloo, Ph.D., R.D.,

FAHA; Kristina S. Petersen, Ph.D., A.P.D., FAHA; Cheryl A.M. Anderson, Ph.D.,

M.P.H., FAHA; Sparkle Springfield, Ph.D.; Linda Van Horn, Ph.D., R.D.N., FAHA;

Amit Khera, M.D., M.Sc., FAHA; Cindy Lamendola, M.S.N., A.N.P.-B.C., FAHA;

Shawyntee M. Mayo, M.D.; and Joshua J. Joseph, M.D., M.P.H., FAHA. Authors’

disclosures are listed in the manuscript.

This scientific statement was prepared by the volunteer writing

group on behalf of the American Heart Association’s Council on Lifestyle and

Cardiometabolic Health; the Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; the

Council on Hypertension; and the Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease.

American Heart Association scientific statements promote greater awareness

about cardiovascular diseases and stroke issues and help facilitate informed

health care decisions. Scientific statements outline what is currently known

about a topic and what areas need additional research. While scientific

statements inform the development of guidelines, they do not make treatment

recommendations. American Heart Association guidelines provide the

Association’s official clinical practice recommendations.