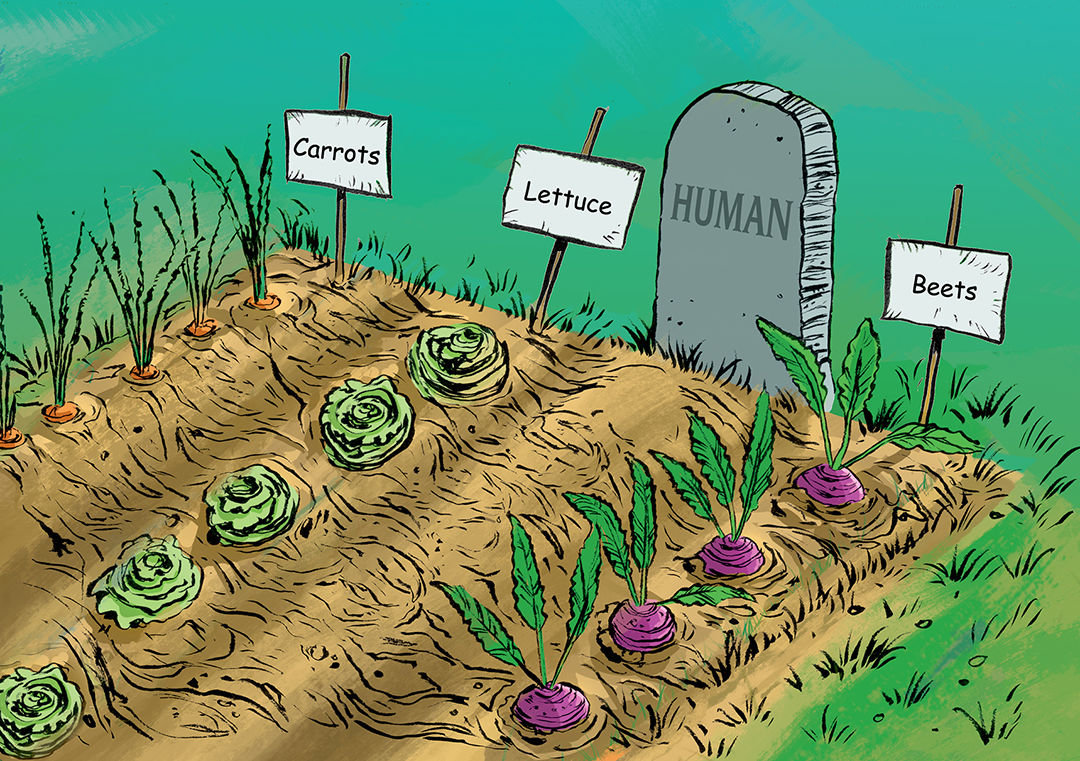

Legislation Would Give Rhode Island Residents Chance to Compost Themselves

By Rob Smith /

ecoRI News staff

What if, when it was your time to go, you could truly leave no trace?A bill filed in the General Assembly this year aims to give Rhode Islanders that exact option.

H6045, introduced by Rep. Michelle McGaw, D-Portsmouth, would allow natural organic reduction facilities to open as part of the death-care industry. The process, more commonly known as human composting, uses techniques similar to regular composting to accelerate the conversion of human remains to soil.

In a recent interview with ecoRI News, McGaw said she was inspired when she read a story earlier this year that New York became the sixth state to legalize the practice.

“This was something we don’t often think about,” McGaw said. “I’m of that mindset that I spend a lot of my time and my days trying to figure out what we can do to promote good environmental policy and live my life in a way that is friendly to our environment.”

The idea of the bill, she said, is to give people another option for disposition. Six other states, including Rhode Island, are considering legislation legalizing the practice.

The Seattle-based company Recompose has taken the lead in bringing a green revolution to the death-care industry, offering human composting services and organizing a movement to legalize the practice nationwide. The company’s home state of Washington passed a law that went into effect in May 2020.

The process, as described on Recompose’s website, surrounds human remains with wood chips, alfalfa, and straw in a specifically designed vessel, where microbes break the body down into soil. The process takes between eight and 12 weeks.

Once the process is complete, the soil can be returned to the family for however they choose to use it, or families can donate it to Bells Mountain in southern Washington.

McGaw said she was surprised by the amount of support from people who reached out to her about her legislation, but said she expects there be to be objections based on religious grounds.

The current death-care landscape of burying embalmed human remains or cremating them is not environmentally sustainable. Conventional burials in cemeteries across the nation take up huge amounts of resources every year. According to a 2012 report from the Berkeley Planning Journal, cemetery burials use 30 million board feet of hardwoods, 2,700 tons of copper and bronze, 104,272 tons of steel, and 1,636,00 tons of reinforced concrete.

“Digging in a modern cemetery in the United States is much like digging through a toxic waste site,” wrote Alexandra Harker, the report’s author.

Also buried every year are 827,060 gallons of embalming fluid, primarily formaldehyde, a probable carcinogen.

The same study showed that soil samples taken at coffin depth revealed elevated concentrations of metals used in casket construction, including copper, lead, zinc, and iron. On top of the burial process, many cemeteries nationwide contain vast water-consuming grass lawns, which are bad for the environment on their own.

Meanwhile, cremation isn’t much of a better alternative. Cremation of human remains can release persistent toxic emissions into the atmosphere, including particulate matter, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and heavy metals, according to the Green Burial Council.

Many crematories use fossil fuels to reach the required temperatures to cremate human remains. In 2019, National Geographic reported that a single cremation produced an average of 534.6 pounds of carbon dioxide, for an estimated annual nationwide average of 360,000 metric tons of C02.

Cremation is becoming increasingly popular. The latest statistics available from the Cremation Association of North America, a trade group for the industry, showed that in 57.5% of all deaths in 2021, people chose to be cremated.

Either major option in death care is becoming prohibitively expensive. Wired reported in 2021 that the average cost of a U.S. funeral was $9,000, and the average cost of a cremation was $6,000.

McGaw said she expected a new version of her bill to be introduced in the coming weeks, with a new bill number, that would have language that better reflects the current death-care industry.

“This is the way I live my life. And I’d love to be able to do this, you know, at the time of my death, and how can we make this happen here in Rhode Island,” McGaw said.