‘Half the Population in the State is Struggling All the Time’

By Colleen Cronin / ecoRI News staff

EDITOR'S NOTE: Charlestown has almost no rental housing other than summer vacation rentals. - Will Collette

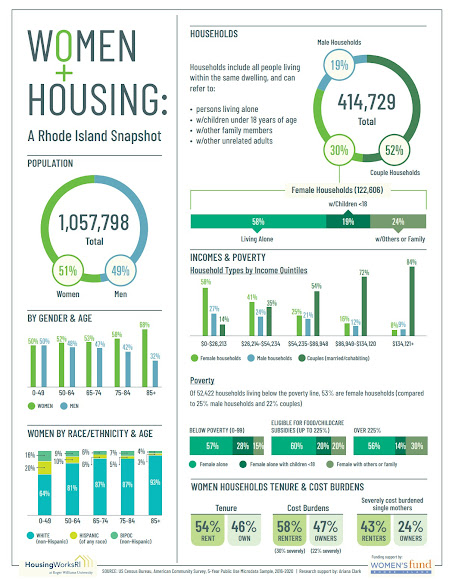

Most women households in Rhode Island are renters who pay a disproportionate amount of money on housing compared to their incomes, according to data from HousingWorks RI’s Women and Housing: A Rhode Island Snapshot.

The data from that snapshot shows that more than half of

women households in the state are renters, and nearly 60% of them pay more than

30% of their income on housing, making them “cost-burdened.”

“It’s not surprising,” said Brenda Clement, HousingWorks

RI’s executive director. She explained the housing policy group, run out of Roger

Williams University, published the snapshot and hosted an event at the end of

March to highlight some of the housing disparities women face.

“Women are generally earning less,” Clement

said. The fastest growing jobs in the state — in retail, home health care,

assisted living — “don’t pay a housing wage,” and the majority of people

working those jobs are women, she said. Then as women get older, they are more

likely to live alone, dependent on a fixed income.

Camilo Viveiros, executive director of the George Wiley Center, a Pawtucket-based nonprofit focused on social and economic justice issues, said he frequently sees these issues impact his members, who are mostly women of color.

Of the 17 people helped by the center’s anti-eviction

program, 11 have been women, Viveiros said.

Between wage disparities and women’s disproportionate

roles as caretakers, “all of it combined creates this precarity,” he said,

which can lead to more housing instability.

Viveiros knows a woman who initially mostly interacted with the center as a volunteer, spearheading fundraisers for those impacted by Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico and hoping to organize the tenants in her apartment complex. But when the pandemic hit, and she was faced eviction from her longtime home, as a disabled women living alone and on social security, there was little resources beyond the center to help her. And eventually, she had to move.

“The pandemic had a way of exposing some of the already

difficult situations that people have been struggling with for years and

years,” Viveiros said. It also highlighted how the road from cost-burdened to

homeless is not a long stretch.

A woman living by herself in a rented apartment in Little

Compton estimates she pays about 65% of her income toward housing. The woman,

who asked to remain anonymous for fears of professional and personal

repercussions, runs a small business in town and holds two other jobs to make

ends meet. Depending on the year, her income ranges from about $27,000 to

$32,000.

“I try my best to make it but it’s pretty hard,” she

said. “I don’t get a break.”

As a tenant, she worries sometimes about finding a place

to move if her landlord decides to increase her rent or sell the building.

For now, her housing seems like it’s stable. She lives

with just her puppy and has been able to save a little bit here and there, so

she feels lucky compared to some. But if she had to move, she would be hard

pressed to stay in town and might even have to move out of state.

“I’ll stay for as long as I can,” she said. “I’m still

praying about it.”

Programs that could assist women in Rhode Island could

also help anyone with housing insecurity, including older adults, individuals

with disabilities, and members of the LGBTQ+ community who are more likely to

experience homelessness, Clement and Viveiros said.

More rental subsidies and more affordable housing —

perhaps spurred by more inclusive zoning laws — could help, Clement said.

Viveiros said he hopes more funding will be directed at

the most vulnerable populations. “We need to look at the root causes of the

systemic and policy issues,” he added.

“None of these are new problems,” Clement said. “It just

is a reminder, you know, that well over half the population in the state is

struggling all the time.”