Group of characters work together annually at Rhode Island BioBlitz to find spore-producing organisms

By Colleen Cronin /

ecoRI News staff

|

| Members of the fungi team search for specimens near a stream on Narragansett Indian tribal land. (Colleen Cronin/ecoRI News) |

AUKE UT NAHIGANSECK/CHARLESTOWN, R.I. — While mycologist Lawrence Millman waited for his ride to the 24th Annual Rhode Island BioBlitz from the Providence Train Station, he did something he rarely does: he used his cellphone to call the reporter who was supposed to pick him up.

Millman only bought a cellphone two years

ago, but often refuses to use it and rarely gives out his phone number. He

usually arranges things via email, including rides, because he doesn’t own a

car and let his driver’s license lapse years ago.

For the Rhode Island Natural History

Survey’s annual BioBlitz, which he comes down from his home in Cambridge,

Mass., to attend annually, he wore an old T-shirt aptly screen printed with

mushrooms, hiking boots, and a bit of gray scruff.

He has been coming to the event — a 24-hour

scramble to survey the number of species at a particular Rhode Island site —

for a decade, he thinks. It’s one of the only mycological events that he still

likes attending.

“Male myco-files of a certain age are very

eager to compete with each other,” Millman said.

The fungi enthusiast doesn’t like crowds

and doesn’t much care for the norms and rules of life, much like the numerous

but elusive organisms he likes to study.

|

| Mycologists Lawrence Millman, right, comes from his home in Cambridge, Mass., every year to participate in the Rhode Island BioBlitz. (Colleen Cronin/ecoRI News) |

Arriving at the Narragansett Indian Tribe’s

reservation in Charlestown, called auke ut Nahiganseck, meaning “We dwell

here,” Millman noted that dry conditions might limit what the fungi team could

find during the June 9-10 weapon-free hunt.

At each BioBlitz, participants split up

into groups based on the different types of organisms they are searching for,

with the goal of identifying as many species as possible within 24 hours.

Last weekend there were more than two dozen teams looking for everything from mollusks and mammals to mosquitoes and mosses.

For insects alone, there are nine teams

dedicated to different subgroups. (During the course of this BioBlitz, this

reporter learned that a ladybug is indeed not a bug, but a beetle, because it

has chewy mouth parts rather than “piercing” ones.)

Many participants come back to the same

groups year after year, some create T-shirts and give themselves nicknames. For

example, the vascular plant team goes by the “The Plantathletes,” and the

lichen group is known as “The Cladonia Crazies.”

The fungi group is called “The Fun Guys,”

although Millman asked that the name not be used in this story. The team didn’t

have matching T-shirts, but many were wearing mushroom paraphernalia, including

earrings, graphic tees, and socks.

Millman, who has been studying,

identifying, and writing about fungi the longest, is just one of several

mycologists in the group who participate in the annual species search.

Deana Tempest Thomas, who founded the Rhode Island Mycological Society, led the group

this year. Ryan and Emily Bouchard run the Mushroom

Hunting Foundation and have led the fungi group in the past.

Noel Rowe, who is actually a primate

expert, is an annual attendee and started the fungi group at one of the first

Blitzes, when he realized no one was taking a tally of these organisms.

Patrick Verdier is a member of the

Mycological Society and is usually identified as the man with the microscope

getting a closer look at fungi.

In addition to these more seasoned

mycologists, this year’s fungi fun group included many newcomers of different

ages and backgrounds. Millman said he thought this year’s group was the most

diverse fungi team, which helped lead the group to some interesting

discoveries.

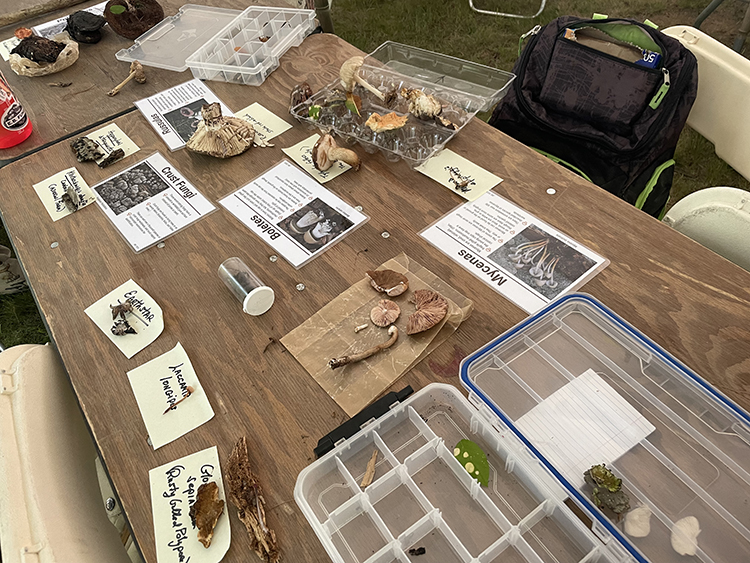

|

| Fungi specimens collected during the 24 hours of the BioBlitz. (Colleen Cronin/ecoRI News) |

After checking into Science Central — what

BioBlitz calls its tented-base camp, where most of the tricky species’

identification happens — and picking out fungi stickers to adorn their name

tags, the fungi team listened to the opening ceremonies, which celebrated the event’s

first time on Narragansett Indian tribal land.

Then, at exactly 2 p.m. last Friday, Rhode

Island Natural History director David Gregg sounded the blown horn, and the

mycologists scampered off to the woods.

The first find was Hydnoporia olivacea,

announced by Millman.

“Ahhh, the spreading olive tooth,” Emily

Bouchard said, as Millman spelled out the Latin name.

“Yes! That’s it!” he said, showing the

specimen to the crowd.

Spreading olive tooth isn’t the typical

fungus found in fairy tale pictures books or fancy French soups. It doesn’t

have a stalk or a cap. Instead, it’s got a small profile, it’s brown, and it

was growing on a fallen branch.

For the novice mycologist, it’s hard to

distinguish from the tree itself.

“We’re not going to find what we’d usually

find this time of year,” Millman told the group, because of the dry weather and

constant wind. “Most of what we are going to find is in and on the wood.”

Millman has no problem looking for these

types of smaller fungi; in fact, they are the kind he favors. He doesn’t care

for the rock stars of the fungi world, the edible kind, unless they are being

eaten by something other than a human. He once had a girlfriend, now an ex,

tell him he was much more interested in fungi than her.

“I said, ‘No, that’s not true. I’m more

interested in that, but not far more interested in that,’” he recalled, with a

laugh.

That perspective is much different than

some other members of the group, including the Bouchards. As founders of the

Mushroom Hunting Foundation, the pair teach people how to hunt for and cook

edible mushrooms.

“Larry is much more into small things,”

Ryan Bouchard said. “He just wants to take an interest in what they are and what

they’re doing in the ecology.”

|

| A photo of a fungus under a microscope. (Colleen Cronin/ecoRI News) |

As the group made its way through the dry

wooded areas, they found a few more specimens, but decide to head to a wetter

area for better results.

Just before they reached a stream on the

reservation, someone found an interesting specimen on a tree branch.

“Wait a minute,” said Millman, halting the

group and pulling out a tiny microscope to examine further. The branch was

covered with cup fungi, he said.

“I say it’s a disco party because if you

find one, you’ll find a bunch,” Thomas said of the Pezizaceae family of fungi

that tend to grow in the shape of a cup.

“And Deana can hear the disco party from a

great distance,” Millman joked.

Moving on to the stream and its banks, the

collection of specimens kept growing.

Team members waded through muck and under

branches in between reminders that everyone needed to keep drinking water and

perform tick checks.

Rowe, the primate specialist, held a basket

full of makeshift specimen containers — pill bottles, fishing lure boxes, egg

cartons — to carry the fungi of various shapes, sizes, and colors back to

Science Central for further study.

He said part of what makes identifying

fungi specimens so difficult is the sheer number of them. There are thought to

be six times more types

of fungi than types of plants.

As he spoke, Samantha Young, who told ecoRI

News she only got into fungi this past year after meeting Thomas, found an

interesting specimen — a mushroom that appears to grow, at least partially, in

water.

Fungi do a lot of weird things, like this,

Thomas said. Some grow in extreme places, some glow, some smell like peanuts.

The bleeding mycena, which they

also found by the stream, appears to bleed from its stalk when it’s snapped.

Despite their oddities, fungi share a

common thread in their ecosystem importance. Many have a symbiotic relationship

with trees, and without fungus, nothing would decompose, Thomas noted.

After about a dozen more finds, the group

was shocked to look at the clock and find it was time to head back to Science

Central for dinner.

“Time flies when you’re having fun and fungi,” Thomas said.

Right after dinner and a talk from

Narragansett Indian tribal member Thawn Harris, it started to rain, which got

the fungi group a little excited.

During the nighttime walk, Thomas took out

a black light to look for more specimens. Many fungi glow under these lights

and expose themselves even better than during the day.

It was actually the draw of glowing

mushrooms that got Millman interested in fungi to begin with.

With a doctorate in English, Millman

traveled the world learning about oral histories of Indigenous people he said

he felt akin to because their separation from the rest of society.

Speaking with some First Peoples in Canada,

he had heard numerous stories of fungi and their medicinal or malevolent uses,

but it wasn’t until he spotted a bioluminescent mushroom on a trip to North

Carolina circa 1990 that he realized he needed to know more.

“That ignited everything, so to speak,”

Millman said. Among his dozens of titles, Millman has written several books

about fungi, both about the science and mythology surrounding them.

Having long used mushrooms as a muse,

Millman said he finds the current fascination with fungi, from their starring role in HBO’s

“The Last of Us” to their impact at fashion

shows, interesting, namely because their usefulness to humans is of little

interest to him.

“I actually like mushrooms better than I

like human beings,” he admitted.

Though he does like some people a lot,

including his compatriots at BioBlitz. He and Rowe struck up a friendship at a

Blitz years ago, when Millman dethroned him as the top mycology expert. But

Rowe doesn’t mind, and even has hosted Millman overnight while he visits Rhode

Island for a Blitz.

Thomas noted this BioBlitz was her and

Millman’s friendaversary. Two years ago, they met at the Natural History

Survey’s lone fall hunt. That year was record breaking for the fungi team

because autumn is prime fungi time.

“I was immediately impressed by her

mycological skills, which she continually denies,” Millman said of Thomas.

Thomas refers to Millman as her mentor.

And in some ways, the student is getting

the chance to surpass the teacher.

“She periodically one-ups me,” Millman

said. During the course of last weekend, there were a few things she identified

before him. “I keep telling her she’s a real mycologist, and she keeps denying

it.”

Looking at specimens under a microscope

last Saturday, 18 plus hours into the Blitz, the fungi became their own worlds.

Verdier wielded the machine and showed how

a tiny brown smug can change into individualized spores producing mounds,

cracked, and separated, like a lava flow on a mountain side instead of a fungus

on a branch.

He used the microscope to try to identify

some of the specimens that had been brought in from the field. It’s nearly

impossible to identify some species of fungi by sight only. In addition to using

microscopes, mycologists can look at spore imprints and even use DNA testing to

get an exact match.

The substrate, the material that the

specimen grows on, can also be important in identifying a species in a kingdom

where cousins look exactly the same but only grow on a particular plant or

tree.

By the end of the 24 hours, the fungi team

had found some 80 species, according to Thomas, though some were taken by

Millman, with permission from the Narragansett Indian Tribe, to make more

accurate identifications at home.

The number was surprising for the

conditions, Thomas said, but they were looking for small things and those

things added up.

Millman noted the size of the team also

probably contributed to the high count, although he said the number of species

they found doesn’t really matter to him. He’s not a big statistics guy, and to

him, the BioBlitz is about something more than the numbers can say.

“The virtue is getting outdoors, educating

people, coming up with some notion of how healthy a habitat is,” he said on the

drive back to the train station.

For all the similar events he has attended,

he said the Rhode Island BioBlitz is his favorite.

“I think it’s the best,” he said. “It’s the

most serious and the most amusing.”