New law requires public water systems test for forever chemicals

PFAS found in Exeter, at URI and Wood River

By Colleen Cronin / ecoRI News

staff

|

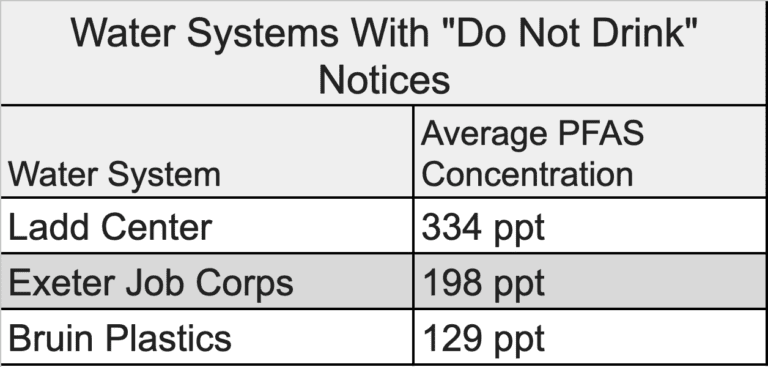

| A new law requires public water systems to test for forever chemicals. (Colleen Cronin/ecoRI News graphic) |

The Ladd Center and Exeter Jobs Corps on the former Ladd

School property in Exeter and Bruin Plastics in Burrillville can no longer use

their wells for drinking water after they tested above 70 parts per trillion

(ppt) for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

A law that was

passed last year, modified earlier this year, and went into effect July 1,

mandates that public water systems test for the chemicals, which are found in

firefighting foams to food packaging and floor wax and are linked to several cancers, fertility

issues, and developmental delays in children.

Of the 170 public water systems in the state, 164 have

sampled their water, according to RIDOH spokesperson Joseph Wendelken. The

remaining six have until Aug. 10 to report their samplings to be in compliance

with the law.

In addition to requiring new testing, the General

Assembly also created a new interim drinking water standard of 20 ppt for PFAS.

Systems that test above 20 ppt must notify their customers and enter an

agreement with RIDOH within 180 days to remediate the impacted wells, but only

systems that tested above 70 must issue “do not drink” notices to their

customers.

RIDOH and its toxicologist determined that 70 ppt put consumers at a much higher health risk than 20 ppt and decided to set the higher number as the “do not drink standard,” Amy Parmenter, chief administrator for RIDOH’s Center for Drinking Water Quality, told ecoRI News.

“Seventy was previously what the [Environmental Protection Agency] had been using for their health advisory, so there had been some science behind that previously.”

The EPA is currently trying to push for more stringent requirements.

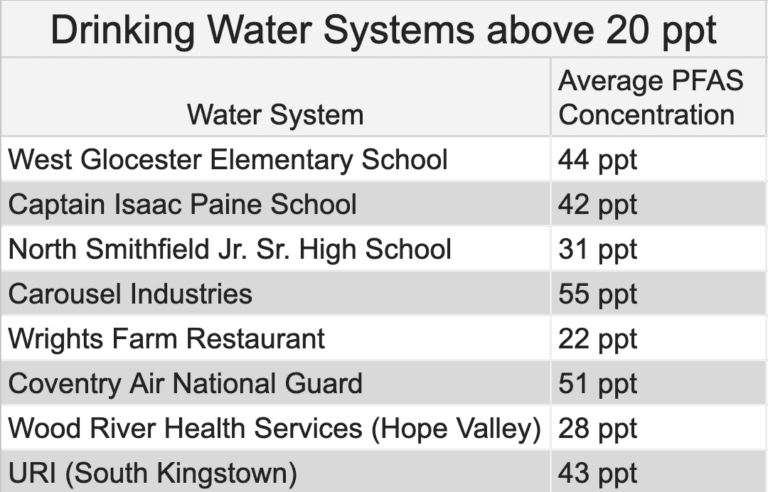

In addition to the Ladd Center, Exeter Jobs Corps, and

Bruin Plastics, eight other water systems tested between 20 and 70 ppt.

The department has posted the test results, which are an average of the first sample

and a confirmatory sample, for the systems that exceeded the standard.

RIDOH wanted to prioritize the systems with higher

results, but will eventually post the results from all the systems, Wendelken

said.

For those systems that have been placed under a no drink

order, water sources are being provided.

According to Lisa Watling from Bruin Plastics’ marketing

department, even before the no drinking water order, employees didn’t drink

from the tap because of concerns about the water, so the order didn’t have a

big impact, she said.

Water will be trucked in for tenants at the Ladd Center

and Exeter Job Corps, according to David Preston, spokesperson for the Quonset

Development Corp., the water system provider for the area.

“Planning for a more permanent solution is well

underway,” he wrote in an email to ecoRI News.

The Exeter Job Corps Center has also been providing water

since the results were announced, a Job Corps spokesperson wrote in an email.

Of those remaining systems that have wells that tested

between 20 and 70 ppt and did not receive a do not drink order, several already

have access to alternative water sources.

|

| (Colleen Cronin/ecoRI News graphic) |

The well at the Air National Guard Station in Coventry

that tested 84 ppt, then 18 ppt, for an average of 51 ppt, has been shut down

since February, according to Col. Michael Grzybowski, facilities management

officer for the Rhode Island National Guard.

There are three additional wells that tested below the

thresholds and “provide more than enough water,” Grzybowski said. “We have no

current plans to remediate the inactive well,”

The Captain Isaac Paine School in Foster is also no

longer using a well that tested above 20 ppt, although legally it could, and is

instead opting to provide bottled water, according to a public notice it sent

out. The school has also already started the engineering process for a new well

and treatment center and is working with RIDOH and the state Department of

Education to accomplish it.

Two other schools also tested above 20 ppt: West

Glocester Elementary School and North Smithfield Junior and Senior High School.

Neither responded to questions about whether the wells were still in use.

Carousel Industries, a cloud communications service

provider in Exeter, tested at 55 ppt but could also not be reached by phone.

Wright’s Farm Restaurant in Burrillville tested 2 ppt

above the interim standard — the lowest concentration of those wells that exceeded

20 ppt — and has already switched to another well in its system, according to

owner Frank Galleshaw. Galleshaw also said when water was being drawn from the

other well, it was filtered before making its way to customers, and that the

filtered water had tested much lower.

“We are making sure that when folks come to Wright’s

Family Restaurant, they are safe,” he said.

A well at Wood River Health Services in Hopkinton also

tested above 20 ppt but for the time being is still in use, according to CEO

and president Alison Croke. Croke said patients and staff have been notified

and that there are resources besides faucets for drinking water.

A well at the University of Rhode Island that tested at

43 ppt is also still operating. Because URI’s system mixes water from multiple

wells, the actual concentration of PFAS in the water consumed may be much

lower, according to URI spokesperson Anthony LaRoche.

“URI is in the process of implementing a series of

upgrades to its water system that are designed to reduce PFAS to levels well

below the Rhode Island interim drinking water standard,” he said.

Water systems can install a treatment method to remove

PFAS from water or can opt to use a different water source. For example, the

Oakland Water District stopped using its well in

Burrillville after it saw high PFAS results in 2017 and instead had its

customers hook up to Harrisville’s system.

Both moving to a new source (when possible) and

installing a treatment system are expensive, costing potentially millions of dollars,

but RIDOH’s Parmenter said funding is available through the EPA, the Bipartisan

Infrastructure Law passed last year, and the Rhode Island Infrastructure Bank.

“PFAS is treatable,” Wendelken said, which he called a

“silver lining.” But he noted “it’s not a quick fix.”