What is the difference between nationalism and patriotism?

Joshua Holzer, Westminster College

|

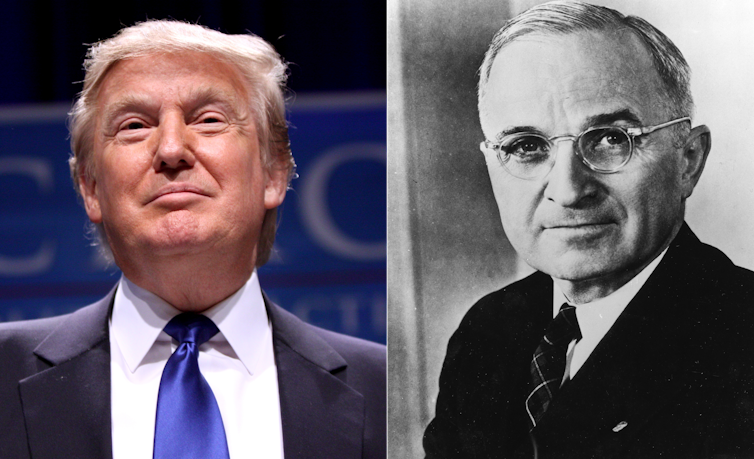

| Donald Trump, left, and Harry Truman: Two former presidents who had different ideas about nationalism and patriotism. The Conversation, with images from Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-NC |

During his presidency, Donald Trump said, “We’re putting America first … we’re taking care of ourselves for a change,” and then declared, “I’m a nationalist.” In another speech, he stated that under his watch, the U.S. had “embrace[d] the doctrine of patriotism.”

Trump is now running for president again. When he announced his candidacy, he stated that he “need[s] every patriot on board because this is not just a campaign, this is a quest to save our country.”

One week later he dined in Mar-a-Lago with Nick Fuentes, a self-described nationalist who’s been banned from Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube and other platforms for using racist and antisemitic language.

Afterward, Trump confirmed that meeting but did not denounce Fuentes, despite calls for him to do so.

The words nationalism and patriotism are sometimes used as synonyms, such as when Trump and his supporters describe his America First agenda. But many political scientists, including me, don’t typically see those two terms as equivalent – or even compatible.

There is a difference, and it’s important, not just to scholars but to regular citizens as well.

|

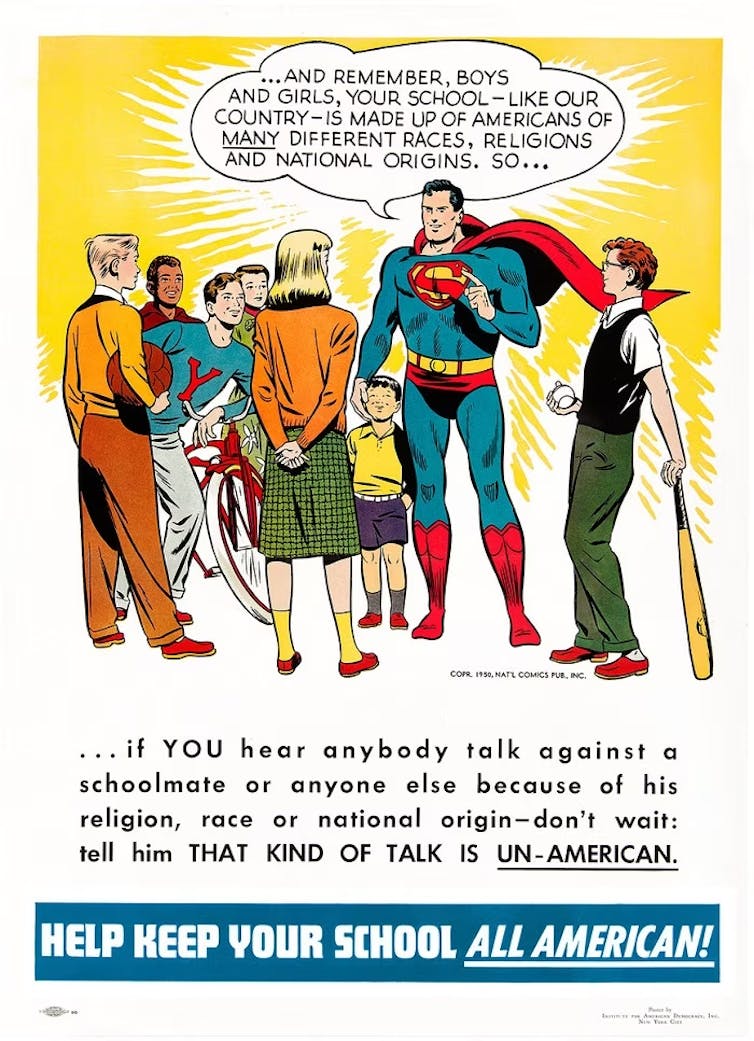

| An image from 1950, colorized in 2017, shows Superman – a refugee from another planet and a character created by two Jewish immigrants to the U.S. – teaching that patriotism should drive out nationalism. DC Comics |

Devotion to a people

To understand what nationalism is, it’s useful to understand what a nation is – and isn’t.

A nation is a group of people who share a history, culture, language, religion or some combination thereof.

A country, which is sometimes called a state in political science terminology, is an area of land that has its own government.

A nation-state is a homogeneous political entity mostly comprising a single nation. Nation-states are rare, because nearly every country is home to more than one national group. One example of a nation-state would be North Korea, where almost all residents are ethnic Koreans.

The United States is neither a nation nor a nation-state. Rather, it is a country of many different groups of people who have a variety of shared histories, cultures, languages and religions.

Some of those groups are formally recognized by the federal government, such as the Navajo Nation and the Cherokee Nation. Similarly, in Canada, the French-speaking Québécois are recognized as being a distinct “nation within a united Canada.”

Nationalism is, per one dictionary definition, “loyalty and devotion to a nation.” It is a person’s strong affinity for those who share the same history, culture, language or religion. Scholars understand nationalism as exclusive, boosting one identity group over – and at times in direct opposition to – others.

The Oath Keepers and Proud Boys – 10 of whom were convicted of seditious conspiracy for their role in the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol – are both examples of white nationalist groups, which believe that immigrants and people of color are a threat to their ideals of civilization.

Trump has described the events that took place on Jan. 6, 2021, as having occurred “Peacefully & Patrioticly”. He has described those who have been imprisoned as “great patriots” and has said that he would pardon “a large portion of them” if elected in 2024.

There are many other nationalisms beyond white nationalism. The Nation of Islam, for instance, is an example of a Black nationalist group. The Anti-Defamation League and the Southern Poverty Law Center have both characterized it as a Black supremacist hate group for its anti-white prejudices.

In addition to white and Black racial nationalisms, there are also ethnic and lingustic nationalisms, which typically seek greater autonomy for – and the eventual independence of – certain national groups. Examples include the Bloc Québécois, the Scottish Nationalist Party and Plaid Cymru – the Party of Wales, which are nationalist political parties that respectively advocate for the Québécois of Québéc, the Scots of Scotland and the Welsh of Wales.

Devotion to a place

In contrast to nationalism’s loyalty for or devotion to one’s nation, patriotism is, per the same dictionary, “love for or devotion to one’s country.” It comes from the word patriot, which itself can be traced back to the Greek word patrios, which means “of one’s father.”

In other words, patriotism has historically meant a love for and devotion to one’s fatherland, or country of origin.

Patriotism encompasses devotion to the country as a whole – including all the people who live within it. Nationalism refers to devotion to only one group of people over all others.

An example of patriotism would be Martin Luther King Jr.‘s “I Have a Dream” speech, in which he recites the first verse of the patriotic song “America (My Country 'Tis of Thee).” In his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” King describes “nationalist groups” as being “made up of people who have lost faith in America.”

George Orwell, the author of “Animal Farm” and “Nineteen Eighty-Four,” describes patriotism as “devotion to a particular place and a particular way of life.”

He contrasted that with nationalism, which he describes as “the habit of identifying oneself with a single nation or other unit, placing it beyond good and evil and recognizing no other duty than that of advancing its interests.”

Nationalism vs. patriotism

Adolf Hitler’s rise in Germany was accomplished by perverting patriotism and embracing nationalism. According to Charles de Gaulle, who led Free France against Nazi Germany during World War II and later became president of France, “Patriotism is when love of your own people comes first; nationalism, when hate for people other than your own comes first.”

The tragedy of the Holocaust was rooted in the nationalistic belief that certain groups of people were inferior. While Hitler is a particularly extreme example, in my own research as a human rights scholar, I have found that even in contemporary times, countries with nationalist leaders are more likely to have bad human rights records.

After World War II, President Harry Truman signed the Marshall Plan, which would provide postwar aid to Europe. The intent of the program was to help European countries “break away from the self-defeating actions of narrow nationalism.”

For Truman, putting America first did not mean exiting the global stage and sowing division at home with nationalist actions and rhetoric. Rather, he viewed the “principal concern of the people of the United States” to be “the creation of conditions of enduring peace throughout the world.” For him, patriotically putting the interests of his country first meant fighting against nationalism.

This view is in line with that of French President Emmanuel Macron, who has stated that “patriotism is the exact opposite of nationalism.”

“Nationalism,” he says, “is a betrayal of patriotism.”![]()

Joshua Holzer, Assistant Professor of Political Science, Westminster College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.