RI-CHAMP provides real-time information to emergency managers, facility operators

By Tony LaRoche

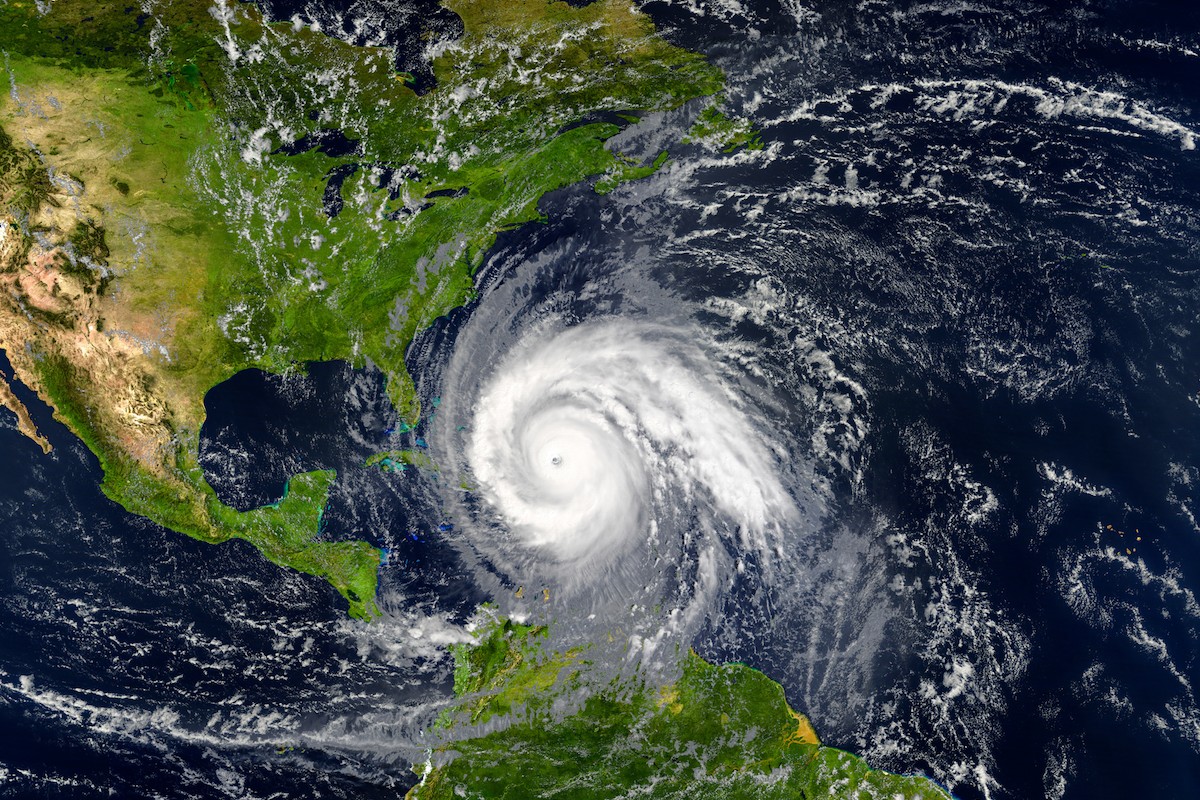

With hurricane season just starting, Rhode Island has a new storm modeling system that will provide state and local emergency management officials with up-to-the-second information on wind strength and flooding to allow them to make real-time decisions.

The Rhode Island Coastal Hazards, Analysis, Modeling, and

Prediction (RI-CHAMP) system, developed by University of Rhode Island

oceanographer Isaac Ginis with a team of colleagues and students at URI, will

be fully operational for the first time this season.

“This is the first system of its kind built in the country,” said Ginis, who developed the system with funding from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. “We are a pilot project to demonstrate that this system can be developed and implemented.”

Recently, members of the Rhode Island Emergency Management Agency held a three-hour training exercise for the system at its Emergency Operations Center in Cranston that included center personnel and representatives of the agency, the Rhode Island Department of Transportation and the Rhode Island Red Cross.

The exercise simulated two recent

storms–Tropical Storm Henri (2021) and last December’s powerful nor’easter that

caused flooding and power outages around the state–to demonstrate in real time

the accuracy of the system’s hazard modeling and storm-impact predictions by

comparing them with the actual conditions of the two storms, Ginis said.

“It was an opportunity for the center’s staff to learn

and practice using information from RI-CHAMP to make real-time decisions during

emergency responses to extreme weather events, such as hurricanes and

nor’easters,” said Ginis. “We believe it went very well and we accomplished all

of our objectives.”

The Rhode Island EMA is still working on how the system will be used in the State Emergency Operations Center, said Thomas Guthlein, deputy director for RI EMA.

“RI-CHAMP has shown its value. We just need to work

out a few process and data issues that we hope to complete this summer. URI has

been a great partner and this project will benefit all Rhode Islanders and

could save lives.”

Ginis has a long history in developing computer models to predict storm strength. He was one of the first scientists to develop a coupled hurricane-ocean model to more accurately predict the intensity of a storm, a system adopted by the National Weather Service.

He is also part of a research

team that is studying the impact of sea-level rise when coupled with extreme

weather as part of a four-year, $1.5 million grant from the National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration.

The URI team has been working on the RI-CHAMP modeling

system to predict the impact of major storms as they approach land for about

eight years, he said.

“When a hurricane approaches land, we are not only

concerned with the strength of the wind, but with flooding–what we call the

storm surge produced by hurricanes,” he said. “We need a special model that

simulates what is going to happen in response to hurricane-force winds to

predict storm surge.”

One of the most important requirements of the model was to represent the complexity of the Rhode Island coastline, Ginis said. It required developing a computational grid with a high spatial resolution to accurately show predicted hazards from wind and coastal flooding.

In some

areas, the model has a spatial resolution of 10 meters. In comparison, the

National Weather Service’s best model in the New England area has a spatial

resolution of 200 meters, he said.

“That allows us to more accurately predict the movement

of water in a specific location. That’s key to predicting storm surge,” he

said.

With that detail, the modeling system has the ability to

calculate hazards to infrastructure in the smallest of areas–such as a generator

room or parking lot. Austin Becker, chair of the URI Department of Marine

Affairs, and several of his graduate students worked with state and local

officials and facility managers to collect data on critical

infrastructure.

“The URI team collected the data across the state, mostly

in the Providence area, about critical facilities,” Ginis said. “We built this

data into our prediction system. As we forecast hazards, we can simultaneously

predict when a facility will be affected. RI-CHAMP includes a web-based, fully

interactive dashboard where emergency managers can see in real time where the

hazards are and what the impact will be on their facilities or

communities.”

“As a decision support tool, RI-CHAMP helps emergency

managers prepare for storms based on specific, actionable data where we used to

rely primarily on instinct and our experience with past storms. The ability to

anticipate and prepare for the specific consequences of a given storm forecast

is a game changer,” said Sam Adams, a Ph.D. candidate in URI’s Marine Affairs

Coastal Resilience Lab who also serves as the University’s full-time emergency

management director.

Along with Ginis and Becker, the URI team included Chris

Damon in the URI Environmental Data Center, who helped design the system’s

interactive dashboard, and Pam Rubinoff, associate coastal manager in the

Coastal Resources Center, who led stakeholder engagement. Also, graduate

students in URI’s Graduate School of Oceanography and Department of Marine

Affairs had an essential role in the development of the system, Ginis said.

The system will be in place for the Atlantic hurricane

season, which runs from June through November. NOAA’s seasonal forecast calls

for 12 to 17 named storms (winds of 39 mph or higher), with 5 to 9 becoming

full hurricanes (winds of 74 mph or higher) and 1 to 4 major hurricanes (winds

of 111 mph or higher).

But there are two climate factors that could affect how

active the season will be, Ginis said. One is the surface temperature of the

ocean in the tropical region–warmer water is favorable to hurricane formation

and intensity, he said.

The other factor is one of two atmospheric phenomena, El

Nino and La Nina, which alternate every two to seven years. El Nino, which is

forecast for this year, is less favorable for hurricanes to form, than La Nina.

“Although El Nino is a phenomenon in the Pacific Ocean,

because of the global teleconnection of wind, it turns out that we have

stronger winds in the tropical regions [of the Atlantic Ocean] aloft in the

higher atmosphere,” Ginis said. “That actually is detrimental for hurricane

formation.

“The question is how soon will El Nino arrive this season

and how strong it is going to be,” he added.

While NOAA’s forecast calls for a less active season than

recent years, Ginis reminds coastal residents that it only takes one storm to

make landfall near them to make it an active season.

“People need to just prepare as usual, regardless of

whether it’s a normal or active season,” he said. “I always like to give this

example: In 1992, we had only seven named storms—well below the average. But

then we had Hurricane Andrew that made landfall near Miami and essentially wiped-out Homestead.”