There are practical strategies for reducing it

William Gardner, University of Washington; Nicholas Kassebaum, University of Washington, and Theresa A McHugh, University of Washington

|

| Anemia symptoms include shortness of breath, dizziness and fatigue. Peter Dazeley/The Image Bank via Getty Images |

Despite this, investments in reducing anemia have failed to substantially reduce the massive burden of anemia globally over the last few decades.

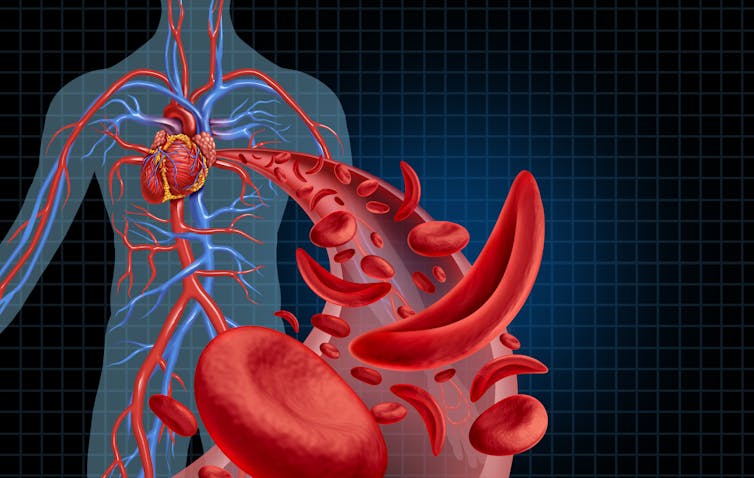

People become anemic when their blood lacks enough healthy red blood cells to carry oxygen throughout the body. This decreased oxygen delivery causes many of the most common symptoms of anemia, including fatigue, shortness of breath, lightheadedness, difficulty concentrating and challenges with work and daily life tasks.

In addition to its direct health effects, anemia can inhibit brain development and fine motor skills in children and heighten the risk of stroke, cardiovascular disease, dementia and other chronic illnesses in older adults.

Anemia during pregnancy can lead to increased rates of anxiety and depression, early labor, postpartum hemorrhage, stillbirth and low birth weight. Infections for both mother and baby are also more likely when the mother is anemic.

We are global health researchers with expertise in epidemiological modeling of anemia alongside other maternal, neonatal and nutritional disorders.

Our work is part of the Global Burden of Disease Study, a large research study comprehensively estimating health loss due to hundreds of diseases, injuries and risk factors around the globe.

Through our analysis, we have produced annual estimates of anemia prevalence by underlying cause for 204 countries and territories, by age and sex, from 1990 to the present. We have collected thousands of data points across hundreds of sources to produce the most comprehensive picture of anemia burden.

Anemia is a widespread problem

Anemia is diagnosed by a simple blood test and can be caused by a number of underlying conditions.

Decreases in healthy red blood cells can occur due to excessive loss of existing red blood cells, such as through bleeding or destruction by the body’s immune system. Anemia can also occur due to decreased production of new red blood cells or changes in the normal structure or lifespan of red blood cells that make them less effective.

Globally, anemia is the third-largest cause of disability: Our recent study found that nearly 1 in 4 people has anemia. This burden is concentrated among children younger than 5 years and adolescent girls and women, one-third of whom are anemic. Anemia rates are particularly high in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, where we estimated that 40% – or two out of every five people – have anemia.

Reductions in anemia rates have been slow and uneven, dropping from 28% to 24% globally from 1990 to 2021. Adult males have fared better, with young children and adolescent girls and women – who bear the highest burden of anemia – showing the least progress. On the positive side, there has been a shift toward milder forms of anemia, which result in much less disability compared to severe anemia.

Reducing anemia means tackling underlying causes

Substantially reducing anemia globally is complicated by its many underlying causes. Dietary iron deficiency is the most common cause across the globe. But other important drivers of anemia include blood disorders such as sickle cell disease or thalassemias, infectious diseases like malaria and hookworm, gynecologic and obstetric conditions, inflammation and chronic diseases.

|

| Sickle cell disease – characterized by crescent or sickle-shaped red blood cells that can block blood flow to the rest of the body – is a well-recognized cause of anemia. wildpixel/iStock via Getty Images |

Young children have increased requirements for iron as their bodies grow, and malnutrition is a common cause of anemia in this group globally.

Iron supplementation has historically been the primary form of treatment and prevention of anemia. This includes large-scale addition of iron to foods such as flour, rice or milk, as well as providing oral iron tablets and intravenous iron, depending on the context and severity.

Some research has suggested that less than half of people with anemia will fully respond to supplemental iron if the underlying causes of iron deficiency remain untreated. For example, cells in our bodies sequester iron as part of the immune response to some infections. Supplementing with iron without treating the underlying infection will do little to solve the iron deficiency in the long run, and it may even be harmful.

Additional interventions include HIV treatment and prevention, with pre-exposure prophylaxis and anti-retroviral therapy. Preventing initial infection with HIV or suppressing the effects of the virus once infected will reduce the anemia burden related to HIV/AIDS.

Other strategies include malaria control methods, such as insecticide-treated bed nets and vaccination, and monitoring and prevention of chronic illnesses such as chronic kidney disease and inflammatory conditions. In combination with a robust supplementation program, these interventions could meaningfully reduce the global burden of anemia.

Anemia makes it hard for nearly 2 billion people worldwide to learn in school, perform at work and take care of their families. We hope our findings will allow for more comprehensive intervention and treatment plans, especially for the most vulnerable – adolescent and adult women, children and the elderly.![]()

William Gardner, Researcher in Neonatal and Child Health at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington; Nicholas Kassebaum, Adjunct Professor in Health Metrics Sciences and Professor of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, University of Washington, and Theresa A McHugh, Researcher and Scientific Writer at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.