Dynamic duo searches high and low for favorite “prey”

By Frank Carini / ecoRI News staff

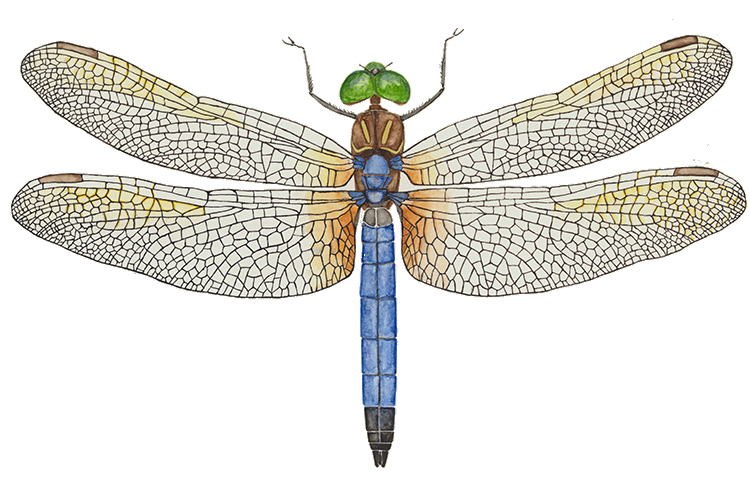

A Nina Briggs illustration of a blue dasher. We saw one during

our Sept. 2 ‘hunt’ through the Great Swamp Management

Area. It is a common dragonfly species in Rhode Island.

Capturing one is a bit more difficult. They can be up in a tree out of reach or hidden in leaf litter below. Catching one by hand is toilsome.

These dragons, glistening in shades of black, blue,

brown, green, red, and yellow, are some of the most colorful creatures on the

planet, with intricate patterns of stripes and spots. To Brown and Briggs, they

are also some of the most elegant insects on Earth.

These aerial assassins have been around for about 300

million years. They survived the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs. They have,

so far, survived humankind’s destructive nature.

They can be found buzzing around in the swampy wilds of

Rhode Island. In the summer, these winged acrobats perform stunts above and

around ponds, lakes, streams, bogs, marshes, and rivers.

On a recent Saturday morning at the Great Swamp Management Area off Great Neck Road, where the two conservationists guide public “hunts,” the longtime Rhode Island residents took this ecoRI News reporter on a 2-hour adventure in search of dragonflies and damselflies.

My guides noted their favorite insects demonstrate

charismatic behavior, possess an ancient evolutionary history, and play an

important role in the ecology of aquatic habitats.

With a degree in wildlife biology — she calls herself a conservation biologist — Brown has long been fascinated with insects. She also has a fondness for birds, particularly birds of prey. They remind her of some other winged creatures.

“I’ve been a birder for a long time, and I’ve always been

particularly fond of raptors,” Brown said. “Dragonflies and damselflies are

kind of like the raptors of the insect world. … They’re drop-dead gorgeous; you

can’t argue with that. Super colorful.”

They are also “well equipped to be predators,” according

to Brown. Their unique skill set makes dragonflies and damselflies a

captivating study.

“Watching them is fascinating,” she said. “Watching them

go through their life, watching them catch other insects, watching them meet,

lay eggs, everything is just fascinating. And maybe most importantly, is

they’re good indicators of ecosystem health. I think looking at invertebrates

is probably far better than waiting for the canary in the coal mine to die.

These insects are going to react sooner.”

Brown — better known as Ginger than Virginia; the latter

is only used when she authors a book or submits scientific data — is the

state’s leading dragonfly expert. She has authored two books about odonates,

the insect order that includes dragonflies and damselflies.

This female autumn meadowhawk dragonfly couldn’t

escape the clutches of my net-wielding guides. It was

released without injury. (Frank Carini/ecoRI News)

Her more recent book — 2021’s Dragonflies and Damselflies of

Rhode Island — teaches readers about the natural history,

distribution, and abundance (or lack of it) of the Ocean State’s 138 odonate

species — two-thirds of which are dragonflies, the rest damselflies. Since the

book was published, Brown and Briggs have documented two more species in Rhode

Island.

The 384-page book features profiles of each species, including habitat characteristics, range, behaviors, dates when they are active locally, and a map indicating where they have been observed. Briggs, a Wakefield resident and talented artist, created a beautiful illustration for each dragonfly and damselfly. She said each illustration took her about 10 hours.

Among the findings highlighted in the book was the

discovery of several species never before recorded in New England, including

the southern sprite and coppery emerald, both of which are southern species

that Brown didn’t expect to find this far north. A species from farther north,

the crimson-ringed whiteface, was also a surprise discovery. Another new

species for Rhode Island, the unicorn clubtail, turned out to be much more

common than expected.

In the book’s preface, Brown noted she was trying to

“paint a positive picture of the future” for dragonflies and damselflies. But,

“despite the successes of conservation agencies, significant threats to our

odonate fauna still exist, even on protected land. Development that leads to

forest loss and degradation of wetlands is a huge issue for these insects and

for so many other organisms that are a part of our lives,” she wrote.

The solution? The longtime friends and collaborators

stressed the importance of conserving and thoughtfully stewarding open space to

protect biodiversity.

“Forests have a profound effect on the health of

watersheds and aquatic habitats,” Brown wrote. “We have to preserve our forests

if we care about nature. … Even after we have protected the forests, meadows,

and wetlands we care about, our job is not done.”

During a 30-minute conversation we had before going

hunting, Brown commented further about the importance of forestland when it

comes to the insects and other wildlife she and Briggs care so much about.

“The relationship between aquatic insects and forest might seem like a strange thing. You know, like why would forests be important?” she said. “Well, forest is important for a number of reasons. First of all, dragonflies and damselflies don’t just live in the water, they live most of their life in the water, but they also fly around on land.

Forest is

important habitat for them. But also forest is extremely significant in

buffering the aquatic habitats that they live in … buffers them from runoff,

pollution, maintains water quality, water temperature, all of those things that

are required for dragonflies and damselflies and other aquatic animals.”

Like her fellow odonate hunter, Briggs has also long been interested in insects. Her scientific involvement, however, came later in life.

“I was constantly scolded by my grandmother for bringing

them in the house and losing them,” she said. “I was an artist until I had my

midlife crisis and decided I would go to school and I would become the Jacques

Cousteau of bug videos.”

Brown, who grew up in the Northeast, and Briggs, who

moved to the Ocean State from Kansas in the 1970s, first connected in the early

1990s. They have been odonate hunting together ever since, which sometimes

means sinking to their knees in swamp mud or standing on a vehicle to better

reach a dragonfly with their sweeping nets.

They are frequently joined on their hunts with Brown’s

husband, Charlie, a longtime Rhode Island Department of Environmental

Management and Coastal Resources Management Council employee who has since

retired. They consider him the best capturer of dragons.

There are some 5,500 species of dragonflies and

damselflies in North America. Dragonflies are the more common of the two, and

both share many of the same physical characteristics and behaviors. Bulging

eyes are set to the sides of the head and each contains thousands of

honeycomb-shaped lenses that provide excellent vision for hunting — and for

avoiding humans swinging large nets.

Their six legs are utilized for catching pray or perching

on vegetation. Their wings are noticeably veined, and the vein pattern varies

by species.

The easiest way to tell a dragonfly from a damselfly is

when they are at rest. When not in flight, a dragonfly’s wings stick straight

out, perpendicular to their body like an airplane’s wings. A damselfly’s wings

fold back so they are in line with their body, giving them a more sleek,

slender appearance at rest.

Dragonflies also have much larger eyes. A dragonfly’s eyes take up most of its head. Damselflies have a space between their eyes. Damselflies are smaller, with bodies that typically range between 1.5 and 2 inches.

Dragonfly bodies are typically longer than 2 inches. In fact, dragonflies are among the largest insects in the world, and their wings, in proportion to their bodies, are quite large, spanning up to 7 inches in some species. Most dragonflies are powerful fliers, and some can fly up to 30 mph. Dragonflies also have thicker, bulkier bodies, while damselfly bodies are thin like a sprig.

The largest species of dragonfly that has been documented

in Rhode Island is the swamp darner, which grows to 3-3.3 inches in length. In

her book, Brown describes them as a “blockbuster of a dragonfly — a glorious

beast with green thoracic stripes and abdominal rings.” Swamp darners are also

the largest dragonfly species in North America.

Both dragonflies and damselflies are voracious predators,

as larvae and adults. As adults, they eat bees, butterflies, flies, mosquitos,

moths, and each other. They catch their prey in mid-air, often chasing them

before capturing them. Adult dragonflies can consume several hundred mosquitos

in a day.

The prodigious predators are also prey for birds, fish,

frogs, spiders, turtles, and a few carnivorous plants.

Their larvae are aquatic, depending on fresh or brackish

water habitats for survival. They feed on other aquatic insects, including

mosquito larvae, tadpoles, and fish. At both the larvae and adult stage,

dragonflies and damselflies are sensitive to degradation of aquatic habitats

and loss of forest cover, making them good indicators of environmental health, according

to Brown.

Much of the data for the 2021 book was collected between 1998 and 2004, when Brown, a Barrington resident, organized an extensive citizen science project that culminated with the publication of the Rhode Island Odonata Atlas, a statewide inventory of dragonflies and damselflies.

About 70 volunteers, including “Westerly Wille” (Bill Bradley) and the “Pine

Swamp Yankees” (Cathy Cressy and Mike Russo), participated in the creation of

the atlas, visiting some 1,100 waterbodies in every community in the state to

document as many species as they could find. More than 13,000 specimens were

collected and identified — 21 of which had never been reported in Rhode Island.

(This checklist was

born from the atlas.)

The 13,000 specimens captured during the six-year project are kept at the University of Connecticut’s Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Department, in a modern collections facility. It’s not open to the public, but serves as a “wonderful” scientific tool for researchers. The specimens are kept in individual envelopes, rather than pinned through the abdomen.

Brown served as an educator and mentor for the atlas

volunteers, a group of beginners who knew little about dragonflies and

damselflies. The effort produced an important biodiversity document.

Early in her career, Brown worked for the Cape Cod Museum

of Natural History. It was during her time at the museum that she published her

first book — 1991’s “The Dragonflies and Damselflies of Cape Cod.”

She moved to Rhode Island in the early 1990s to work for

The Nature Conservancy, where she played a major role in the state’s

since-defunct Natural Heritage Program.

Brown later worked as a biologist with the Rhode Island

Natural History Survey, which, in 2022, named her its Distinguished Naturalist

of the Year. She currently teaches environmental science and nature for Living

In Fulfilling Environments Inc. and for the Audubon Society of

Rhode Island.

Briggs and Brown’s latest project is examining the

population health of the state’s 34 odonate species of conservation interest.

One of those, a dragonfly called the ringed boghaunter, is also one of Rhode

Island’s state endangered insects. Forest loss is the driving factor in the

ringed boghaunter’s endangered status. More the size of a damselfly, at 1.2-1.3

inches in length, ringed boghaunters prefer fens and bogs. They have gray-blue

eyes, a brownish face, and a hairy brown thorax.

Brown noted relentless development and human activity is

degrading habitat that suits dragonflies and damselflies. She said a Richmond

fen that had the largest population of Rhode Island’s only state endangered

odonate — the aforementioned ringed boghaunter — is now upland. There’s no

aquatic vegetation. No water.

“Probably because of two things in combination. One is that humans messed with the watershed and basically removed all of the forest, and a lot of the topography was taken out,” she said.

“There was no longer a

source of water for that little fen. It’s gone. The big concern there is that

that population of ringed boghaunter was the largest in Rhode Island, maybe the

largest anywhere in its range. I’ve talked to people who work on that species,

and nobody’s ever seen as many as we saw there. That probably was a source

population for others in the landscape that were smaller.”

Another rich dragonfly/damselfly habitat, in the

northeast corner of the state, was lost when a shopping center was built. The

pond and its watershed were once home to 52 odonate species.

“They built a huge mall down to the regulatory buffer,”

Brown said. “So that’s pretty much wiped out. It used to be a mucking pond and

had floating vegetation, a foggy shoreline, and open water, so there were all

these micro-habitats. It had terrific diversity.”