The Gulf Stream is warming and shifting closer to shore

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

A new study published today in Nature Climate

Change now documents that over the past 20 years, the Gulf Stream has

warmed faster than the global ocean as a whole and has shifted towards the

coast. The study, led by Robert Todd, a physical oceanographer at the Woods

Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), relies on over 25,000 temperature and

salinity profiles collected between 2001 and 2023.

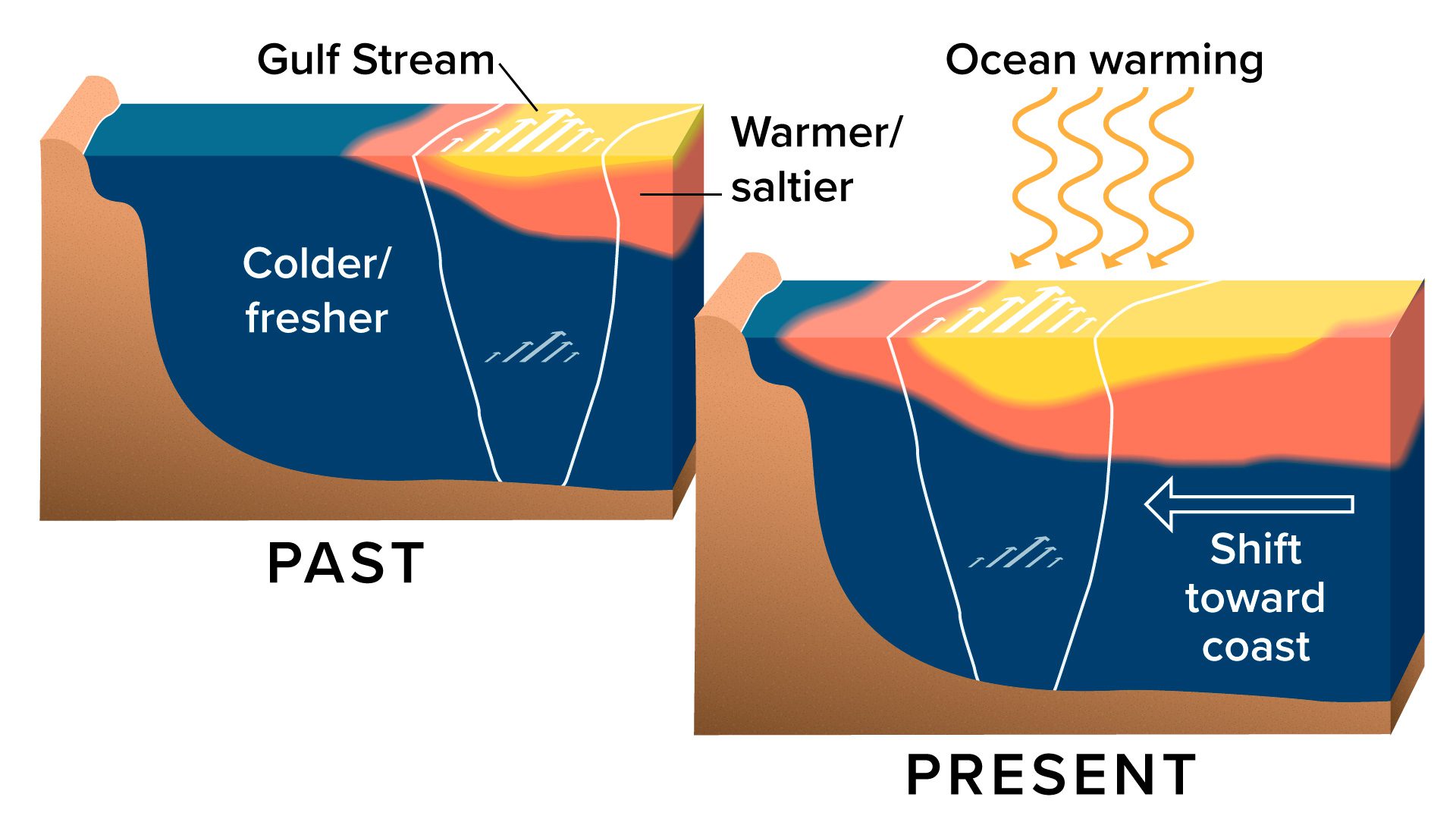

"The warming we see near the Gulf Stream is due to two combined effects. One is that the ocean is absorbing excess heat from the atmosphere as the climate warms," said Todd. "The second is that the Gulf Stream itself is gradually shifting towards the coast."

He and study co-author Alice Ren, also a physical oceanographer at WHOI, found that the near-surface layer of the Gulf Stream has changed most prominently. According to their data, it has warmed on average by about 1°C (2 °F) over the past two decades, becoming increasingly lighter than the waters below.

The team also found the Gulf Stream to be shifting closer to

the shore by about 5 kilometers (3.1 miles) per decade on average, meaning that

the Gulf Stream is moving gradually closer to the Northeastern United States

continental shelf.

"One of the triumphs of this paper is that it

provides observational confirmation of something that numerical simulations

have predicted in a warming climate," Todd said.

They identified these trends using observational data

from Spray autonomous underwater gliders and from the Argo Program, which is an

array of about 4,000 autonomous profiling floats that drift with ocean currents

and move up and down between the surface and about 2,000 meters (6,560 feet) in

depth, collecting data as they rise. Argo is an international program that has

been operating since 1999. WHOI is one of the original Argo institutions and

maintains about 10% of the array.

To better resolve the Gulf Stream, Todd and Ren have

launched Spray gliders off the coast of Florida every two months. Like Argo

floats, the gliders move up and down, but they have the additional ability to

fly through the water and crisscross the Gulf Stream as it carries them

northward. By providing measurements below the surface of the Gulf Stream, the

gliders and floats complement satellites that routinely measure water

temperature at the ocean surface.

"It can be difficult to make predictions about a

current like the Gulf Stream using numerical modeling," said Ren.

"Our paper is important in that it provides observational details about

our changing weather and changing climate."

Just like the jet stream in the atmosphere, the Gulf

Stream sways and oscillates within the ocean. With its average position getting

closer to the coast, Todd pointed out that those large oscillations could more

easily and suddenly influence coastal fisheries -- for example, water

temperature could go from 12°C to 20°C in a very short period of time.

Ocean temperatures are steadily getting warmer as a result of human activities, such as burning fossil fuels, releasing heat-trapping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. However, the basic drivers of the Gulf Stream -- atmospheric wind patterns and the Earth's rotation -- will not disappear in a changing climate, so there is no concern that the Gulf Stream will shut down.

"That's not to say that it won't shift or change

its strength, but those basic ingredients are all it takes to have a warm, fast

Gulf Stream flowing along the U.S. East Coast," said Todd.

Funding for this research was provided by the National Science Foundation, Office of Naval Research, NOAA Global Ocean Monitoring and Observing Program, WHOI, and Eastman. Spray glider operations in the Gulf Stream have relied on P. Deane (WHOI) and the Instrument Development Group at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Alice S. Ren was supported by the Postdoctoral Scholar Program at WHOI, with funding provided by the Doherty Foundation.