Why separating fact from fiction is critical in teaching US slavery

Eric Gable, University of Mary Washington and Richard Handler, University of Virginia

|

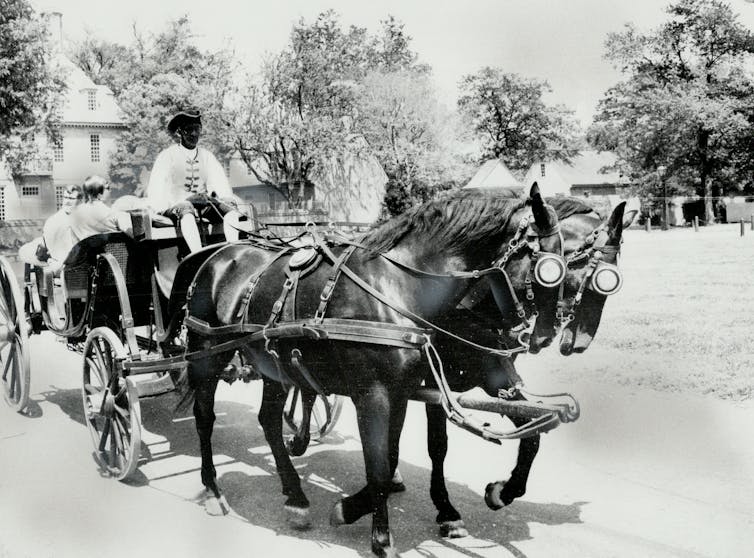

| A Black actor in 1974 impersonating an enslaved man in Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia. George Bryant/Toronto Star via Getty Images |

Does this sentence constitute “propaganda,” as Vice President Kamala Harris proclaimed, “an attempt to gaslight us?”

Or is it a reasonable claim in a discussion of a difficult topic?

Whatever it is, the sentence is of a sort not unique to the teaching of enslavement in Florida. It is, instead, an example of how some Americans transform the racist history of this country into an uplifting – and sanitized – moral lesson.

Truth or fiction?

In our view as cultural anthropologists, the disputed sentence is true as historians define facts – tiny nuggets of truth one can find in archives, artifacts and diaries.

It is a fact that small numbers of the enslaved acquired skills that allowed them to earn money, to save it and to buy their freedom and the freedom of family members.

It is also a fact that freed Black people in the antebellum era helped other Black people to also acquire skills and became part of a segregated Black middle class in many Southern cities.

One might argue that such a sentence, because it is true, should not give rise to protest. But as scholars who have studied how history is taught in America, we learned that this particular nugget is neither trivial nor insignificant.

Instead, the one sentence in Florida’s new standards allows Americans to transform a story about what we today call structural racism into an apocryphal story about Horatio Alger and America’s rags-to-riches melting pot.

As this line of thinking goes, enslaved ancestors of contemporary African Americans labored just as most contemporary Americans’ ancestors labored: at the bottom, but able to climb up the social ladder with hard work and discipline.

And this is the problem: To portray enslaved people as laborers like free laborers is exactly how not to teach about slavery.

But it is a commonly used method that is called a “switching mechanism.” In this example, the story about the horrors of the slave system is transformed into a story about opportunity, success and the American dream.

Switching the story at Colonial Williamsburg

Thirty years ago, when we conducted anthropological research at Colonial Williamsburg, we encountered the same narrative switching mechanism that is occurring now in Florida.

At that time, the world-famous Virginia outdoor history museum depicting a genteel, colonial America was trying to present the public with a truer picture of the past by incorporating the history of what they called “the Other Half” – the enslaved people who had been all but absent from the museum’s past portrayals.

|

| In this 2001 photograph, Black ‘interpreters’ are acting as carpenters in Colonial Williamsburg. Education Images/Getty Images |

But it was difficult, we found, for the museum to sustain a narrative about the evils of the slave system.

That’s because much of its paying audience of white middle-class tourists did not want to dwell on such tales, and second, its “interpreters,” or guides, found ways to switch the narrative.

Starting from a story about the enslaved being someone else’s property, they would transition to one suggesting the enslaved were working for their own advancement.

We heard stories during our research like this:

• Don’t imagine that 18th century Williamsburg was like mid-19th century Mississippi cotton plantations, with families torn apart by avaricious masters, whippings, shackles and rape. Instead, in Williamsburg, slaves were valuable property.

• Consider that your average white yeoman farmer of the time had an annual income of about 20 pounds. Now consider that a highly trained slave cook was worth 500 pounds. Would your average owner be likely to abuse such a valuable piece of property? No! They’d treat that slave like an NFL quarterback!

Such stories conflated an enslaved laborer’s monetary value to his owner and the income of a white laborer. And that is how many visitors we listened to interpreted what they were hearing.

In other instances, we found conflicting messages.

In a skit that took us to the basement of an elite white Williamsburg household during Christmas, we witnessed Black interpreters portraying enslaved houseboys, maids and cooks complaining that they had to work harder than ever to create the festive atmosphere their owners desired.

Meanwhile, upstairs, white interpreters portraying gentlemen conversing waxed philosophical about the evils of slavery coupled with the impossibility of getting rid of it.

|

| A Black actor playing a slave walks past a farmhouse in Colonial Williamsburg in 1995. Nik Wheeler/Corbis via Getty Images |

One concluded that she had witnessed a universal story because workers everywhere grumble about their bosses.

The other pointed out that if she disliked her boss, she could quit her job – something the enslaved couldn’t do.

Still, both were relieved to hear that slavery did not sit easy on the consciences of the white elite.

Structural inequality or Horatio Alger?

Switching mechanisms such as these are hard to dislodge. They remake the worst parts of the American story into a story consonant with the American Dream.

Today, not much has changed in Williamsburg. In Florida and many other states, switching allows designers of history curricula to avoid discussions on the lasting effects of racialized slave labor.

They avoid discussing what that has meant to millions of people who did not, will not and cannot start on the same rung of the ladder of upward mobility that is available to other Americans who do not share a history of enslavement.

In our view, that is not a story that many Americans want to tell, teach or hear.

And so they switch to a different one, in which equal opportunity has been achieved, every one of us is capable of overcoming seemingly insurmountable odds, and failure to rise must be a result of individual weakness and vice.![]()

Eric Gable, Professor of Anthropology, University of Mary Washington and Richard Handler, Professor of Anthropology, University of Virginia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.