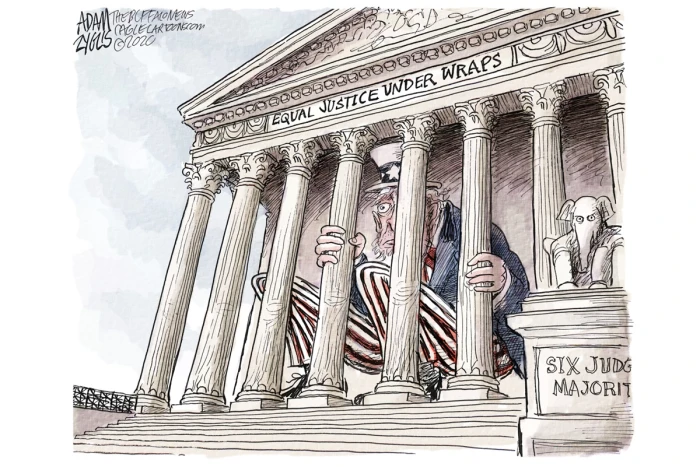

The Supreme Court has adopted a conduct code, but who will enforce it?

by Joshua Kaplan, Justin Elliott, Brett Murphy and Alex Mierjeski for ProPublica

The Supreme Court on Monday released a code of conduct governing the behavior of the country’s most powerful judges for the first time in its history. But experts said it was unclear if the new rules, which do not include any enforcement mechanism, would address the issues raised by recent revelations about justices’ ethics and conduct.

The nine-page code, with an accompanying five pages of commentary, was signed by all the sitting justices and covers everything from the acceptance of gifts, to recusal standards, to avoiding improper outside influence on the justices. The step followed months of reporting by ProPublica detailing undisclosed gifts to Supreme Court justices from wealthy political donors.

The code does not specify who, if anyone, could determine whether the rules had been violated.

The new Supreme Court code’s lack of any apparent enforcement process is “the elephant in the room,” said Stephen Vladeck, a law professor at the University of Texas who studies the court.

“Even the most stringent and aggressive ethics rules don’t mean all that much if there’s no mechanism for enforcing them. And the justices’ unwillingness to even nod toward that difficulty kicks the ball squarely back into Congress’ court.”

Nevertheless, some leading observers of the court described the creation of an explicit, written code as a landmark in the court’s 234-year history.

“The Supreme Court’s promulgation of a code of conduct today is of surpassing historic significance,” former federal appellate judge J. Michael Luttig told ProPublica. “The court must lead by the example that only it can set for the federal judiciary, as it does today.”

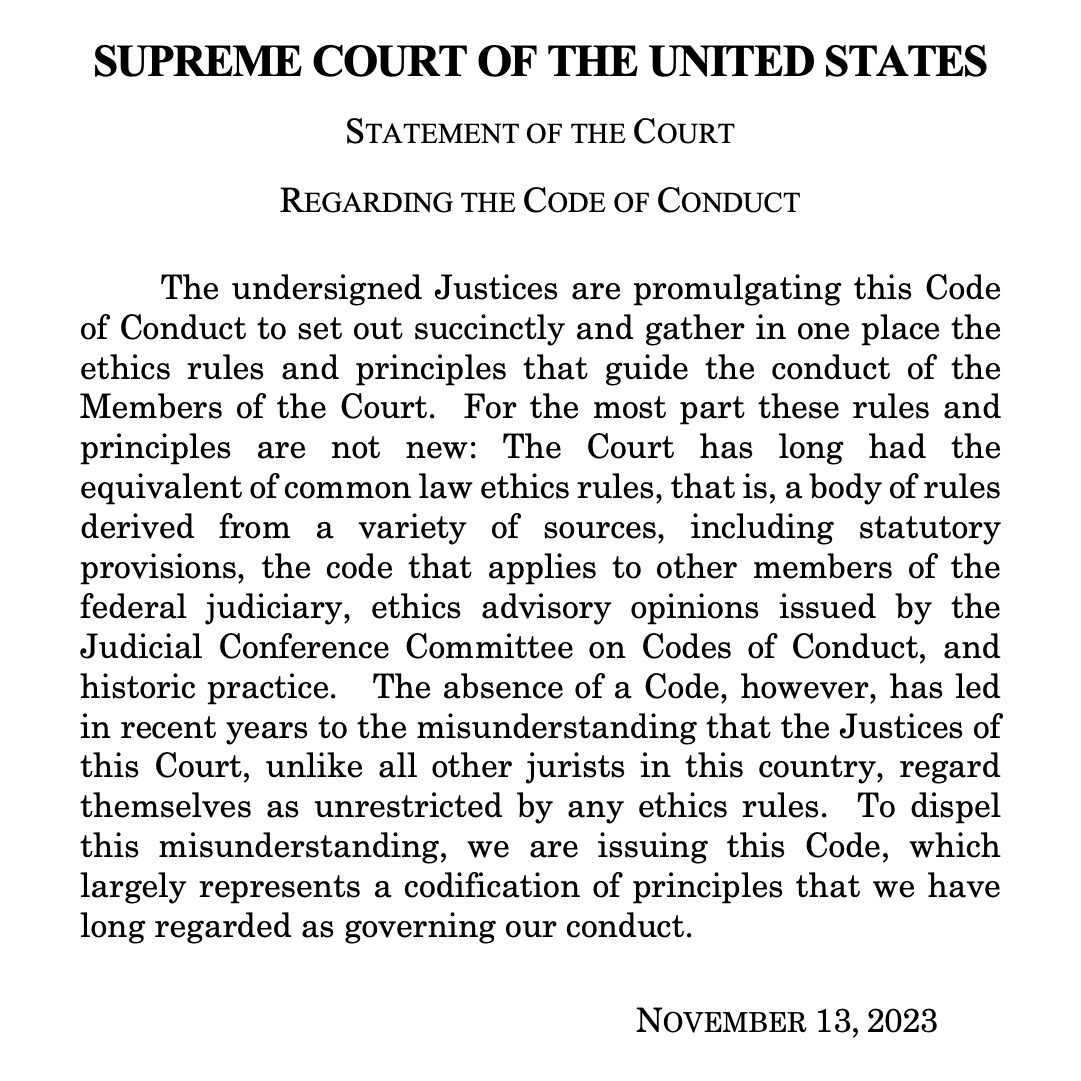

A statement released by the court on Monday accompanying the code said it was formulated to dispel “the misunderstanding that the Justices of this Court, unlike all other jurists in this country, regard themselves as unrestricted by any ethics rules.” It said the code “largely represents a codification of principles that we have long regarded as governing our conduct.”

A series of ProPublica stories this year detailed a pattern of behavior by Supreme Court justices that legal ethics experts said was far outside the norms of conduct for other federal judges. ProPublica disclosed that Justice Clarence Thomas has accepted undisclosed luxury travel from Dallas billionaire Harlan Crow and a coterie of other ultrawealthy men for decades.

Crow purchased Thomas’ mother’s home and paid private school tuition for a relative Thomas was raising as his son. Thomas also spoke at donor events for the Koch network, the powerful conservative activist group. Separately, ProPublica revealed that Justice Samuel Alito accepted a private jet trip to Alaska from a hedge fund billionaire and did not recuse himself when that billionaire later had a case before the court.

Reporting from other outlets, including The Washington Post and The Associated Press, has added to the picture. The New York Times revealed that Thomas received a loan from a wealthy friend to purchase an expensive RV. A Senate investigation later found Thomas did not repay the loan in full.

Federal judges below the Supreme Court have long been subject to a written code of conduct, the foundations of which were set down a century ago following a major ethics scandal in the judiciary. Lower court judges are subject to oversight by panels of other judges, who review allegations of misconduct.

The high court’s new code of conduct is separate from an existing federal law that requires all federal judges including the justices on the Supreme Court to annually report income, assets and most gifts on a publicly available disclosure form.

The law, which passed after the Watergate scandal, has been at the center of the controversies involving Thomas’ undisclosed gifts. Thomas and Alito have argued they were not required to disclose the luxury travel, and Thomas’ lawyer has said that “any prior reporting errors were strictly inadvertent.”

The new document largely echoes the code that applies to lower court judges. Many of its prescriptions are lofty but vague. It requires the justices to “act at all times in a manner that promotes public confidence in the integrity and impartiality of the judiciary.”

It prohibits justices from soliciting gifts, practicing law or sitting on cases where their “impartiality might reasonably be questioned.” It states that the justices should not engage in “political activity,” but it does not define what that means.

Court observers are likely to spend weeks parsing the differences between the new code and that of the lower courts. Small changes were made without explanation. For instance, lower court judges are prohibited from lending “the prestige of the judicial office to advance” their own private interests. The justices are merely prohibited from “knowingly” doing so.

Whether any of the conduct that sparked the push for a formal ethics code would now be prohibited seems to remain open for interpretation. Take Thomas’ appearances at Koch network events.

A federal judge told ProPublica that if he’d done the same as a lower court judge, it would’ve violated prohibitions against fundraising and political activity and he would’ve been subject to a disciplinary proceeding. It’s unclear if the high court’s new code would bar such activities or if each justice would answer such questions for him or herself.

Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., who has introduced a bill that would require the Supreme Court to adopt an enforceable code of conduct, said in a statement that the new code fell short of what is needed.

“The honor system has not worked for members of the Roberts Court,” he said. “This is a long-overdue step by the justices, but a code of ethics is not binding unless there is a mechanism to investigate possible violations and enforce the rules.”

Whitehouse’s bill advanced out of the Senate Judiciary Committee in July, but it has since stalled in the face of GOP opposition. It would create an enforcement mechanism for the court’s code of conduct and set up a process where panels of appellate judges would investigate potential ethics violations.

It’s unclear whether the court’s release of the code will affect the ongoing Senate investigations into justices’ relationships with businessmen and others involved in undisclosed travel and gifts. For months, the Senate Judiciary Committee has been seeking information from Crow and others about undisclosed gifts to Thomas.

Last week, Senate Judiciary Democrats deferred an effort to subpoena Crow in the face of intense Republican opposition on the committee. Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., the panel’s chair, said last week the committee would continue its efforts to authorize subpoenas in the near future.

The court’s new ethics standards are in many ways more lenient than those governing employees of the executive and legislative branches. There are still few restrictions on what gifts the justices can accept.

Members of Congress are generally prohibited from taking gifts worth $50 or more and would need preapproval from an ethics committee to take many of the gifts Thomas and Alito have accepted.

Jeremy Fogel, a retired federal judge in California who had publicly called for the Supreme Court to adopt an ethics code, said Monday that he was “heartened to see that the justices unanimously have recognized the need for an explicit code of conduct.”

“Whether it will make a difference in the justices’ day-to-day actions or in public perceptions of the court remains to be seen,” Fogel said.

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.