Why should taxpayers subsidize stock buy-backs?

SARAH ANDERSON, Inequality.Org

The reasoning? These CHIPS program subsidies, explained Commerce

Secretary Gina Raimondo, “should be used to expand in America, to out-innovate

the rest of the world. Invest in R&D and your workforce, not in buybacks.”

Wielding the power of the public purse against buybacks

makes total sense.

Taxpayers want every dollar of their public investments

to produce maximum benefits. But every dollar spent on stock buybacks is a

dollar not spent on worker wages, R&D, and other productive investments to

stimulate long-term growth and make U.S. companies more competitive. Analysts

have documented how buybacks are associated with reduced capital investment and

innovation and wage stagnation.

And yet in the past two years, S&P 500 corporations

spent record annual sums repurchasing

their own stock—$922.7 billion in 2022 and $881.7 billion in 2021. In the first

half of 2023, share repurchases were down a bit but still an eye-popping $390.5 billion.

What’s the goal of all these buybacks? This financial

maneuver artificially inflates the value of a company’s share price by reducing

the supply on the open market. That keeps shareholders happy. It also

creates huge windfalls for CEOs,

since most of their compensation is in some form of stock-based pay, and their

bonuses are often tied to financial targets that can be influenced by stock

buybacks.

Using public funds as a lever for discouraging this practice is good policy. But why just go after semiconductor companies? Why not all corporations receiving federal funds of any sort?

Chip makers are notorious for their profligate buyback spending.

But so are many other companies that are feeding at the federal trough—or stand

to do so through new legislation.

Stock Buybacks by Low-Wage Federal Contractors

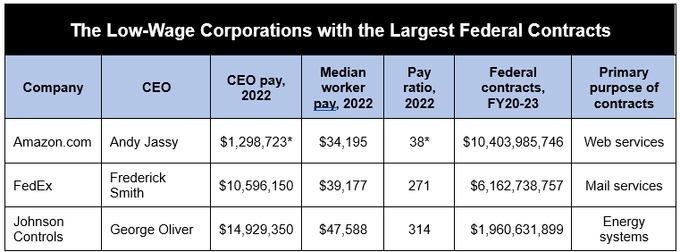

|

| Source: Institute for Policy Studies, Executive Excess 2023. *Jassy accepted modest pay in 2022 after receiving a 2021 stock grant valued at $212 million. |

A recent Institute for Policy Studies report takes a deep dive into the 100 S&P 500 corporations with the lowest median worker wages, a group we’ve dubbed the “Low-Wage 100.”

We found that 51 of these firms are federal contractors, with a combined $24.1 billion in deals during fiscal years 2020-2023. Meanwhile, these 51 low-wage contractors spent nearly $160 billion on stock buybacks.

The largest? Amazon, with at least $10.4 billion in contracts for web services. Since January 2020, the e-commerce goliath has spent $6 billion on buybacks while paying their median worker just $34,195.

These share repurchases have helped pump up Amazon CEO Andy Jassy’s personal

holdings of Amazon stock to $265 million. These millions do not include

the bulk of his 2021 mega-grant, a reward that will vest over 10 years.

FedEx, the second-largest contractor in the Low-Wage 100,

pocketed $6.2 billion from Uncle Sam in fiscal years 2020-2023. FedEx spent

$3.6 billion on buybacks during this period, a maneuver that helped prop up the

value of CEO Fred Smith’s more than $5 billion in personal stock holdings, the

largest stash held by any CEO in the Low-Wage 100.

In 2022, his last year before transitioning to the FedEx

executive chair slot, Smith made $10.6 million, 271 times FedEx median worker

pay. Unlike competitor UPS, where more than 70% of employees

are unionized, FedEx is notoriously anti-union.

Number three on our low-wage contractor list is Johnson Controls. Originally based in Milwaukee, the company moved its headquarters to Ireland in 2016 to lower its U.S. tax bill.

But the company continues to receive major taxpayer-funded federal contracts, a

haul worth nearly $2 billion in FY2020-2023, primarily for upgrading federal

buildings to a more energy-efficient status.

The firm could receive considerably more federal support

over coming years, thanks to new infrastructure and energy legislation. Under

CEO George Oliver’s leadership, the firm has spent $4.5 billion on stock

buybacks since 2020. That contributed to a 139% increase in his personal

stockholdings, to $131.7 million. In 2022 Oliver made 314 times as much as his

typical employee.

Wielding the Power of the Public Purse to Narrow Pay

Disparities

Extending the CHIPS program conditions on stock buybacks

to all firms receiving federal contracts, subsidies, and grants should be a

no-brainer. It would complement President Joe Biden’s support for other tools

for reducing buybacks, including his proposal to quadruple a new 1% excise tax on

share repurchases.

The administration could also do much more to leverage the power of the public purse against extreme pay disparities. The proposed Patriotic Corporations Act could serve as a model.

This bill would grant preferential treatment in contracting

to firms with CEO-worker pay ratios of 100 to 1 or less, among other

benchmarks, including neutrality in union organizing. The Congressional Progressive Caucus has

called on Biden to introduce such incentives.

By encouraging big companies to narrow their pay gaps,

the administration would also help ensure that taxpayers get the biggest bang

for the buck for federal contract dollars. Studies have shown that

companies with narrow gaps tend to perform better because more equitable pay

practices tend to bring out the best in all employees.

The administration should also build on Biden’s executive

order requiring large construction firms involved in public infrastructure

projects to negotiate collective agreements with

their workers. Unions and other pro-worker advocacy groups have called on the

president to expand that requirement to

contractors that provide goods and other services.

In fiscal 2022, Uncle Sam awarded more than $705

billion in unclassified contracts (and an undisclosed amount of

classified contracts). Billions more go out the door every year in the form of

subsidies, grants, and tax credits.

We should view these public funds as a source of power to create an economy that works for everyone. Public money should support the public goodnot line the pockets of overpaid CEOs.

SARAH ANDERSON

directs the Global Economy Project of the Institute for Policy Studies, and is

a co-editor of Inequality.org.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/buyback.asp-Final-5a1ff1b0e4294d8293b5b3a044417e70.jpg)