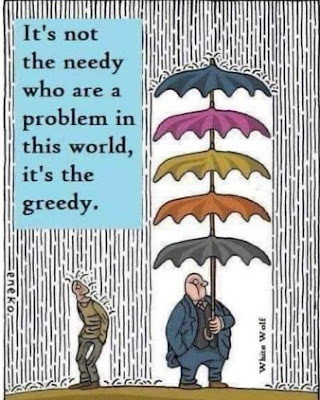

Tax dodging, legal and illegal must stop

SAM PIZZIGATI , Inequality.Org

How can we comprehend—truly comprehend—how concentrated the wealth of our world has become? We have some choices.

We can choose to see the world of concentrated wealth

through the eyes of those who directly serve the richest among us, people like

the veteran Australian sea captain Brendan O’Shannassy, the author of Superyacht

Captain: Life and Leadership in the World’s Most Incredible Industry.

Floating palaces like the $500-million superyacht of

mega-billionaire Jeff Bezos can routinely run their

deep-pocketed owners over $130,000—per day—for basic upkeep. But these

same superyachts, O’Shannassy believes, still

constitute the finest investment individuals of immense wealth can make. They

offer their deep-pocketed owners both security and relaxation, with no whiff of

paparazzi.

Or we could choose to go in a starkly different direction

to better comprehend the wealth of our wealthiest. We could look at these

wealthy through the eyes of those who measure just how concentrated our world’s

wealth has become. Two just-released reports help us do exactly that.

Or we could choose to go in a starkly different direction

to better comprehend the wealth of our wealthiest. We could look at these

wealthy through the eyes of those who measure just how concentrated our world’s

wealth has become. Two just-released reports help us do exactly that.

The first comes from researchers at the Federal Reserve.

Every three years, these analysts release a deep dive into the distribution of

America’s income and wealth, a copiously detailed snapshot of

American household “balance sheets, pensions, income, and demographic

characteristics.”

The latest Fed Survey of Consumer Finances—released last week—covers the changes in American family finances between 2019 and 2022.

Over this three-year span, after taking inflation into

account, typical American family incomes inched up what the Fed describes as “a

relatively modest 3%.” But the incomes of high-income households, the Fed

points out, rose at a much more rapid rate, registering “one of the largest

three-year changes” that Fed researchers have ever encountered.

On the net-worth front, ordinary households taken as a

whole did register gains, the Fed notes, that “far outpaced inflation” between

2019 and 2022, gains that mostly reflect sizeable jumps in the value of

owner-occupied houses. But these same sizeable jumps also put home ownership

increasingly out of the reach of families seeking to become—for the first

time—homeowners.

By 2022, the value of America’s most typical homes was

running 4.6 times our nation’s most typical family incomes, an all-time record

gap. Financial advisors usually recommend that

families should spend no more than three times their annual

income for a home of their own.

Other analysts outside the Fed orbit have crunched the

new Survey of Consumer Finances raw data to paint a plainer

picture of how much wider the wealth gap in the United States has grown since

the Federal Reserve began publishing Survey of Consumer Finance reports

over three decades ago.

Over those decades, a DQYDJ analysis points out, the inflation-adjusted net

worth of the typical American household has gone from $108,501 in 1989 to

$192,084 in 2022.

The net worth of the nation’s richest 1% over that same

span? That wealth has gone, again after adjusting for inflation, from

$5,351,332 in 1989 to $13,666,778 some 33 years later.

Another analysis, from Matt Bruenig at the People’s

Policy Project, has used the new Fed data to calculate the

share of America’s wealth held by each decile—each 10%—of the nation’s

households.

“Overall,” Bruenig concludes, America’s “wealth

inequality remains quite high,” with the top 10% of households owning a

whopping 73% of the nation’s wealth and the bottom half of U.S. households

holding “just 2% of the nation’s wealth.”

The Fed data, analyses like Bruenig’s show, can help us

gain a much-needed sense of just how unequal the United States has become. But

the Fed’s Survey of Consumer Finances can only take us so far.

The Survey’s data shine no spotlight on the richest of our rich and

cover only pre-tax income.

For how the super rich make out after taxes,

we have to look elsewhere—and we now have an exceedingly revealing place to

look. The E.U. Tax Observatory, a research effort begun in 2021 with backing

from the European Union and a variety of academic institutions, has just released a

blockbuster new study entitled Global Tax Evasion Report 2024, “an

unprecedented international research collaboration building on the work of more

than 100 researchers globally.”

Our world’s richest, this new study details, now enjoy

“effective tax rates” that annually cost them no more than a mere 0.5% of their

personal wealth.

Over the last decade, the E.U. Tax Observatory study

notes, a number of individual governments have agreed on major

initiatives to counter international tax evasion. Since 2017, for instance,

banks have been “automatically” exchanging information helpful in identifying

tax evaders. And over 140 nations agreed in 2021 to set an annual 15% “global minimum

tax” on multinational corporations.

But assorted loopholes and “carve-outs” have undermined

these two reforms. Multinationals last year shifted some $1 trillion of their

treasure into tax havens, the equivalent of more than a third of the profits

multinationals booked in 2022 outside their headquarters country. And many

offshore financial institutions, the new E.U. Tax Observatory report adds, are

dragging their feet on deposit disclosure.

Even so, new exchanges of banking data have offshore tax

evasion down by a factor of three, and only 25% of financial wealth held

“offshore” is currently evading taxes. And the fledgling corporate minimum tax

put in place two years ago has generated considerable useful data of its own.

How can the nations of the world go beyond these two

initial reform efforts? The Global Tax Evasion Report 2024 identifies

a half-dozen specific steps the global community can take “to reconcile

globalization with tax justice.”

Three of these recommendations highlight common-sense

proposals that ought to be able to gain broad international support. One

recommendation, for instance, calls for “the creation of a Global Asset

Registry to better fight tax evasion.”

The other three recommendations on the E.U. Tax

Observatory’s reform agenda seem certain to face some serious political

pushback—from the fans of grand fortune.

One of these three bold proposals calls for new

mechanisms that would enable the taxing of wealthy people “who have been

long-term residents in a country and choose to move to a low-tax country.”

Another would “reform the international agreement on minimum corporate taxation

to implement a rate of 25% and remove the loopholes in it.”

The boldest proposal of all: a call for a new “global

minimum tax” on the world’s billionaires equal to 2% of their net worth.

Moving forward on proposals like these, the E.U. Tax

Observatory report stresses, wouldn’t immediately require thumbs-up from large

numbers of nations. Unilateral action by small groups of nations “can pave the

way” eventually for more “nearly global agreements.”

The reforms the E.U. Tax Observatory is advancing, the

Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz adds in his introduction to the Global

Tax Evasion Report 2024, “may seem impossible to attain, but so was

undermining bank secrecy and introducing a minimum tax on corporations just a

few years ago.”

And if the world doesn’t continue moving boldly forward

on confronting corporate and billionaire tax evasion, what then? Failure on

that front, Stiglitz argues, would mean more than inadequate revenue for

confronting global inequalities, pandemics, and climate change.

“If citizens don’t believe that everyone is paying their

fair share of taxes—and especially if they see the rich and rich corporations

not paying their fair share—then they will begin to reject taxation,” Stiglitz

projects. “Why should they hand over their hard-earned money when the wealthy

don’t?”

In effect, Stiglitz concludes, the “glaring tax

disparity” that our richest now enjoy “undermines the proper functioning of our

democracy.”

We either fix that disparity or suffer the catastrophic

consequences.

SAM PIZZIGATI ,

veteran labor journalist and Institute for Policy Studies associate fellow,

edits Inequality.org. His recent books include: The Case for a Maximum Wage

(2018) and The Rich Don't Always Win: The Forgotten Triumph over Plutocracy

that Created the American Middle Class, 1900-1970 (2012).