Klan hate includes American Catholics

William Trollinger, University of Dayton

|

At 10:30 p.m., the quiet was shattered by a series of explosions, as 12 bombs went off throughout campus.

Frightened students discovered that, while damage was minimal, there was an eight-foot burning cross on the edge of campus.

Running to tear it down, they were confronted by several hundred Klansmen screaming threats from 40 to 50 cars.

It wasn’t the first time Dayton’s residents had endured terror from the Ku Klux Klan. Hundreds of neighbors poured out of their houses and charged at the hooded invaders. The Klansmen sped away, and the students and others extinguished the fire and tore down the cross.

The KKK is most infamous for violently terrorizing African Americans. But in the 1920s its hatred also had other targets, especially outside the South.

This version of the KKK, known as the Second Ku Klux Klan, harassed Catholics, Jews and immigrants – including students and staff at Catholic universities like Dayton, where I am a historian of American religion. All of this is the focus of my 2013 article, “Hearing the Silence.”

The Second Ku Klux Klan

The KKK emerged in the South in the years immediately after the Civil War. Its goal was to use whatever means necessary – including a great deal of murderous violence – to force newly freed African Americans into conditions close to slavery.

Having succeeded, the original Klan all but disappeared by the end of the 19th century. But in the wake of the blockbuster film “Birth of a Nation” – which celebrated the original KKK as having “redeemed” the defeated South – the organization was reborn in Georgia in 1915.

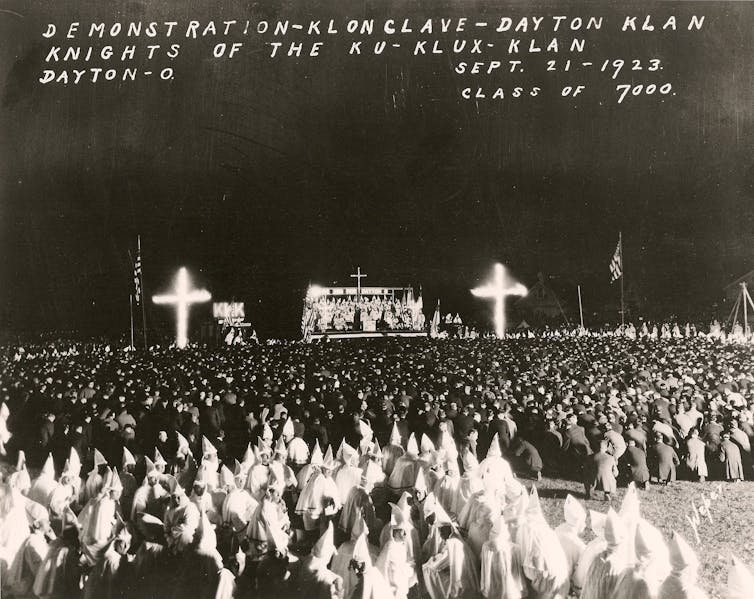

This second KKK only attracted a few hundred members over the next few years. But it exploded upon the national scene in the early 1920s, thanks to anxieties about immigration, race and communism. In fact, the white-robed Klansmen with their fiery crosses – a symbol borrowed from “Birth of a Nation” – very soon attracted between 1 million and 5 million members.

The second KKK was truly national, with more members in the Midwest and West than in the South. As the reporter Timothy Egan powerfully chronicles in his book, “A Fever in the Heartland,” “the Klan owned the state” of Indiana. In 1925, “most members of the incoming state legislature took orders from the hooded order, as did the majority of the congressional delegation.”

It is possible that Ohio had nearly as many members in the 1920s. Historian David Chalmers – who counted 400,000 Ohioans in the KKK at the organization’s peak – commented that “there was a time when it seemed the mask and hood had become the official symbol of the Buckeye State.”

|

| Anna Doss and Mrs. Theodore Heck, wife of the Ohio Commander of the Klan, with a baby at a Klan event in Ohio around 1925. Bettmann via Getty News |

Emulating the first KKK, the second Klan used horrific violence, including lynchings, to try to terrify African Americans into submission.

To be “100% American” also meant that you were Christian. The second KKK was the quintessential white Christian nationalist organization, and it defined ideal citizens by their race, creed and birth.

When Klansmen were initiated into the organization, members sang “Just as I am Without One Plea,” a hymn that adores Jesus as the “Lamb of God.”

Yet the group portrayed Jesus as one of them: the First Klansman.

Anti-Catholic campaigns

Actually, being Christian wasn’t enough. To be 100% American, in the Klan’s view, meant that you were a white Protestant Christian.

In the years between 1890 and 1920, a flood of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe came to America, a large percentage of whom were Catholic or Jewish.

While the Klan was – and still is – strongly antisemitic, in the 1920s its members were particularly worried about Catholics, as there were many more of them. This was certainly the case in Dayton, where 35% of churchgoers were Catholic, thanks to an influx of immigrants who worked in the city’s factories.

In response to the Catholic “threat,” at least 10% of Daytonians – some 15,000 people – joined the KKK in the early 1920s, with some estimates placing the number as high as 40,000.

As was the case elsewhere in the Midwest, the Klan’s presence in Dayton was visible in rallies and parades that attracted thousands of Klansmen, Klanswomen and supporters – not to mention the burning crosses intimidating Catholics and Jews in working-class neighborhoods. As one Dayton resident of those years later recalled, the “threat of Klan violence was always there.”

|

| N.W. Cleverly, a member of the Klan from Ashtabula, Ohio, before a Ku Klux Klan parade in Washington, D.C., in 1925. FPG/Archive Photos/Getty Images |

As part of their intimidation campaign, KKK members repeatedly slipped onto campus to set crosses on fire. Rumor had it that the police force was filled with Klansmen; whether or not that was true, city authorities made little effort to intervene.

But as historian Linda Gordon has noted, “targets of Klan aggression were not always passive or nonviolent themselves.” Students at the University of Notre Dame, for example, stopped a KKK parade and rally, then damaged the headquarters of the local Klan.University of Dayton students fought back, too. They repeatedly chased Klansmen off campus, calling on them to “show their faces.”

At one point, football coach Harry Baujan, hearing that another cross burning was about to commence, exhorted his players to “take off after them” and “tear their shirts off” or “whatever you want to do.”

Lingering legacy

The second KKK peaked in influence and membership around 1925. Over the next few years, however, the Klan was afflicted by a series of scandals, the most famous of which involved the leader of the Indiana KKK – in effect, the most powerful Klansman in America – who raped and murdered his secretary. The KKK had faded from view by 1930, but not without achieving many of its aims.

For one thing, its extraordinary violence, including lynchings, helped ensure that white supremacy would remain the order of the day in the South – as it did for the next few decades.

In addition, the Klan and its sympathizers won the fight on immigration. In 1924, Congress passed the Johnson-Reed Act, which remained on the books until the 1960s. This law drastically reduced the number of immigrants who could enter the U.S. from Southern and Eastern Europe – that is, reducing the number of Catholic and Jewish immigrants – and essentially cut off all immigration from Asia.

One of the tragic effects came in the 1930s and 1940s, as the act made it very difficult for Jewish refugees fleeing the Holocaust to get into the U.S..

While the second KKK faded from view in the late 1920s, a third emerged in the 1950s and 1960s to lead the charge against the Civil Rights Movement. Today, Klan membership is miniscule, as the KKK has been supplanted by more tech-savvy hate groups.

The Second Ku Klux Klan argued that to be truly and fully American one must be the right race, the right ethnicity, the right religion. One century after the Dayton bombing, such sentiments persist in the United States.![]()

William Trollinger, Professor of History, University of Dayton

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.