URI researchers lead new study

The coldest days of winter are here for

many, making the frigid Arctic Ocean feel closer. Despite its distance from

most people, “forever chemicals” have reached this region.

A sampler is deployed into the Arctic Ocean.

(Photo: Alfred Wegener Institute)

But research led by URI Graduate School of Oceanography Professor Rainer Lohmann suggests that per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) won’t stay there indefinitely.

In a new study published in Environmental Science & Technology Letters, Lohmann

and his co-authors report the Arctic Ocean potentially exports as many PFAS to

the North Atlantic Ocean as enters it, circulating the compounds around the

world.

PFAS are chemicals that have been used in such products as popcorn bags, carpets, and fire extinguishing equipment at airports and on military bases. They’re sometimes called “forever chemicals,” since there is no effective, natural way for them to break down once they’re released into the environment.

“PFAS enter the ocean through a combination of atmospheric deposition and various discharges from industries, contaminated sites and wastewater treatment plants,” says Lohmann.

To get to the Arctic Ocean specifically, some PFAS hitch a ride in the air and fall onto the ocean’s surface, but others enter from adjacent oceans.

The potential impacts of these compounds on marine organisms, depends on which PFAS are present and at what concentrations. These factors are ever-changing as water flows between the Arctic Ocean and the North Atlantic Ocean.

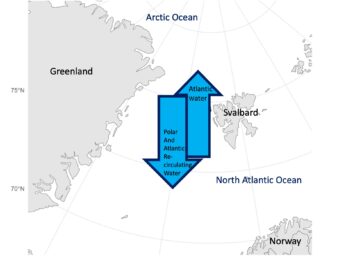

These water bodies are connected by the Fram Strait, which sits to the northeast of Greenland near the Svalbard archipelago. Warm water travels north on the eastern side of the strait, and cold water flows south along the western side, providing a dynamic gateway for PFAS transportation.

So, Lohmann

and colleagues, including GSO alumnus Matthew Dunn ‘23 and Marine Research

Associate Simon Vojta,wanted to track the movement of PFAS in this

region and identify how water circulation influences the mix of contaminants in

the Arctic Ocean.

The researchers deployed passive sampling systems, which took up PFAS into a sorbent-filled microporous membrane from water as it flowed past. They put the systems at three locations in the Fram Strait, and at four depths in each location.

After a year, the team retrieved

the systems and measured the collected PFAS using liquid chromatography-mass

spectrometry, a process that separates compounds from a mixture so that they

can be measured and quantified. The researchers observed that:

- Ten

PFAS were detected in at least one passive sampler, however one substance

detected in the area by previous research teams wasn’t among them.

- Two

compounds known as PFOA and PFOS, which are being phased out, were present

at the highest levels. Newer, short-chain PFAS were also routinely

present.

- Surprisingly,

several PFAS were found in water below 3,000 feet deep. The team suggests

that these compounds could have gotten there by attaching to particles as

they fell to the seafloor.

This last finding is surprising because,

as Lohmann says, “That water is ‘old,’ as it has not been in contact with the

atmosphere for 50 or even hundreds of years. Typically we expect this water to

be free of manmade industrial compounds, except that in this case there has to

be an additional pathway for the PFAS to reach those depths, most likely

attaching themselves to settling particles.”

The team calculated the amounts of PFAS

flowing in each direction through the Fram Strait. Their data showed in one

year around 123 tons traveled into the Arctic Ocean and about 110 tons moved

into the Atlantic Ocean. According to the researchers, these values are the

largest of any pollutant reported in the Fram Strait, demonstrating how

significant the back-and-forth circulation of PFAS is in the Arctic Ocean.

“PFAS are present in much greater concentrations than other contaminants we

have been looking at previously,” Lohmann says.

The authors acknowledge funding from the

University of Rhode Island Sources; Transport, Exposure and Effects of PFAS

(STEEP) Superfund Center; and the Alfred Wegener Institute LTER Hausgarten

program.