Data shows RI's rich pay the least and the poorest pay the most

The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy [ITEP] released a report on January 9 entitled Who Pays? a comprehensive report that “assesses the progressivity and regressivity of state tax systems by measuring effective state and local tax rates paid by all income groups.” In other words, the report assesses the fairness of our state and local tax system.

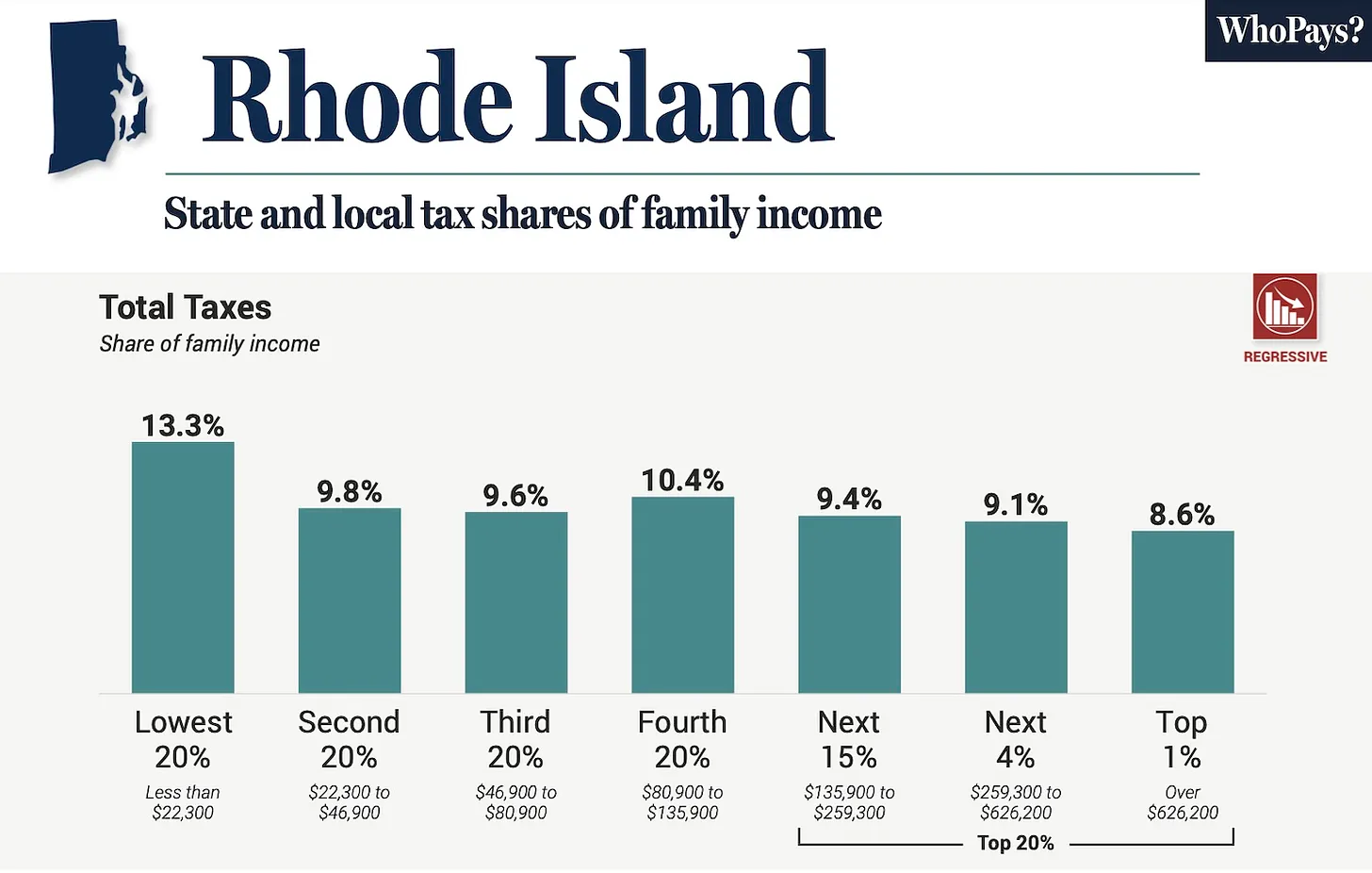

In national rankings featuring all 50 states and the

District of Columbia, Rhode Island ranks #31 out of 51 in terms of having a

regressive tax structure, meaning that the top one percent, those earning more

than $626,200 a year, are paying 8.6% of their income in taxes while those in

the lowest 20%, earning less than $22,300, are paying 13.3% of their income in

taxes.

I spoke to Alan Krinsky, Director of Research and

Fiscal Policy at the Economic Progress Institute [EPI]

to dig into the report with me. EPI is a “nonpartisan research and policy

organization dedicated to improving the economic well-being of low- and

modest-income Rhode Islanders.”

Steve Ahlquist: Rhode Island has the country's 31st

most regressive state and local tax system. One thing that jumped out at me is

that income disparity in Rhode Island grows larger after state and local taxes

are collected. Does this mean that the state's tax policies exasperate the

problem of income disparity?

Alan Krinsky: Yes. In other words, before we involve

state and local income taxes, there are disparities, [but] once we add in state

and local taxes, the disparities are somewhat worse. We want to get to where

the state isn't making things worse.

Steve Ahlquist: And maybe we could get to a place where the state is making things a little bit better, especially for low-income people.

Alan Krinsky: Correct. And I think about six states

on the list do that.

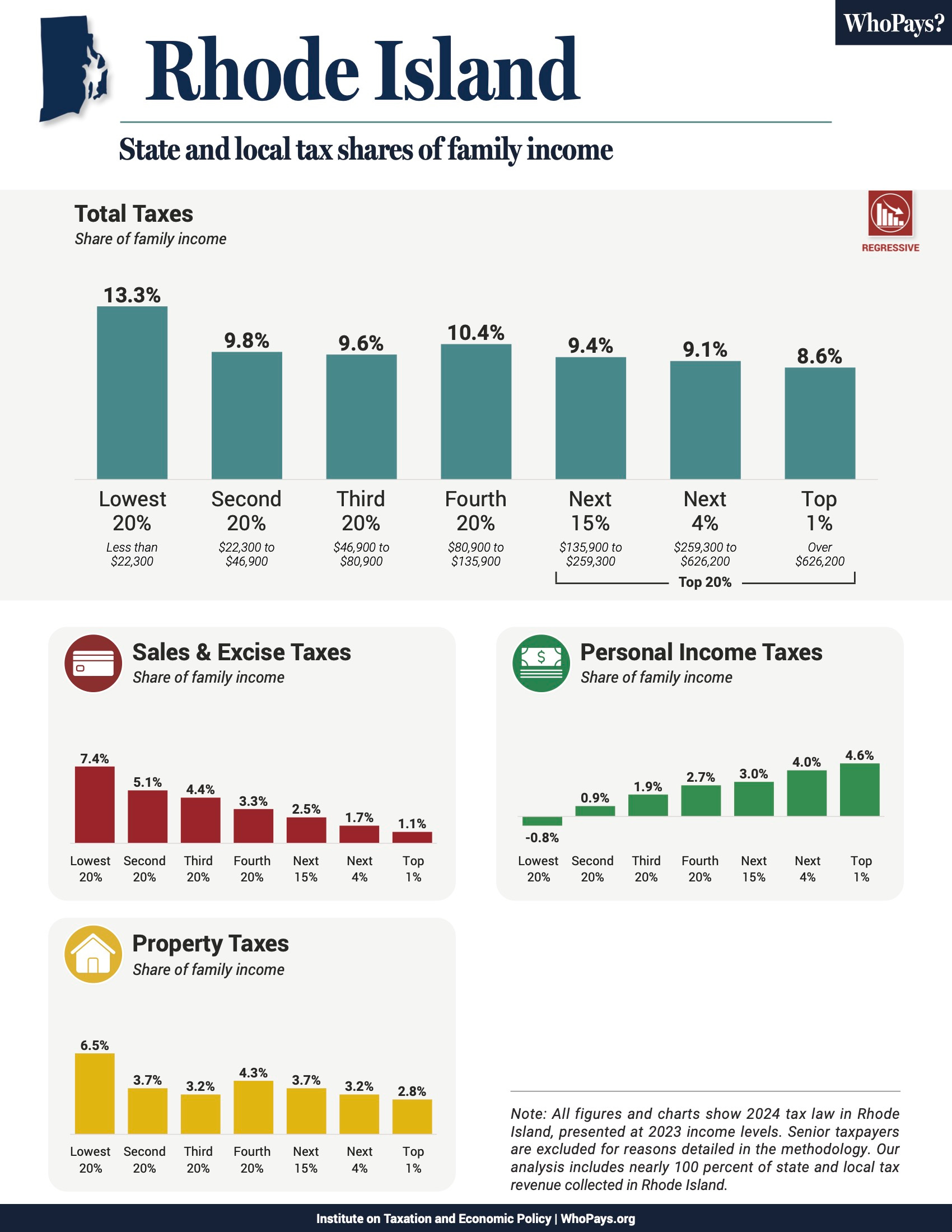

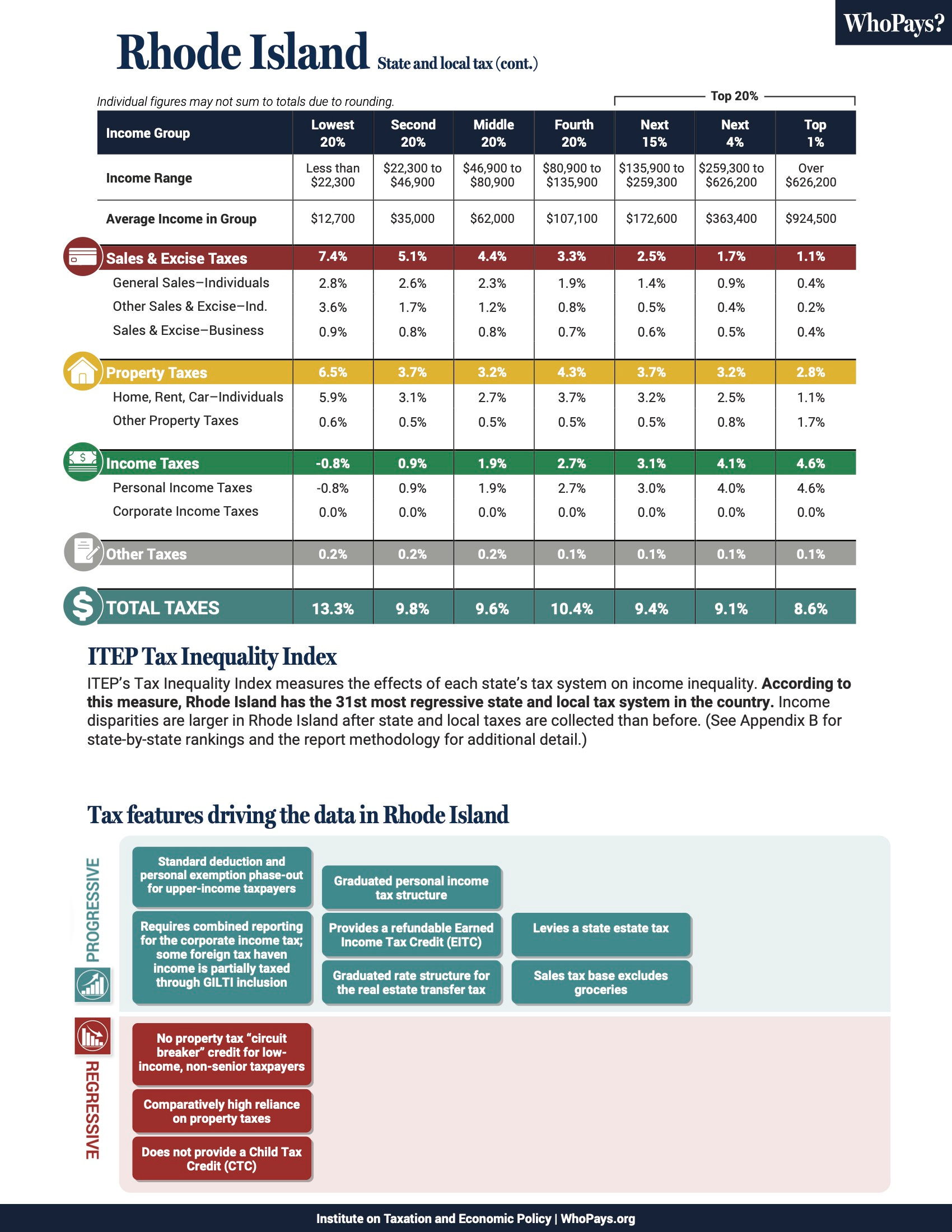

Steve Ahlquist: The report separates key elements of

Rode Island's tax policy into two broad categories, “progressive” and

“regressive.” Presumably, we could move towards a more fair tax policy by

lessening the impact of regressive policies and improving the impact of

progressive policies. So what should we be doing?

Alan Krinsky: I think there are a couple of ways to

go about this and things that could be done in the short term during this

legislative session. The first thing I would do is make the personal income tax

system more progressive by increasing taxes on the top 1%. Looking at the ITEP

charts, people in the top 1% of income pay the lowest percentage of their

income in state and local taxes compared to the other groups - and a lot less

than the lowest 20%.

Doing that, by itself, won't make our tax system

equitable. That won't get us to a place where the state is not making things

worse than before.

So at the other end would be something like decreasing

the tax burden on the lowest 20% by increasing the refundable state Earned Income Tax Credit and creating

a refundable child tax credit. Strengthening the estate

tax would also help because that's mostly affecting people at

the very top of the income chart.

Steve Ahlquist: One thing I hear from the other side

of this issue is that sure, the richest 1% are paying less, as a percentage of

their total income, but overall, they contribute more to the system than people

at the lower end.

Alan Krinsky: In terms of absolute dollars, that's

correct. The people who have the highest income - I don't have the numbers -

but they are paying more in absolute dollars. But if we think about the tax

burden and tax fairness, we can see that the tax burden on them is less than it

is on someone who's paying an absolute amount that's less but is consuming a

larger portion of their income.

Steve Ahlquist: It seems to me that a truly

progressive tax structure would be taxing the top 20% at a level that is higher

than those in the bottom 20%.

Alan Krinsky: We do have a somewhat progressive

income tax structure, but it's not progressive enough to shift that burden.

Steve Ahlquist: Nationally, we're hearing

President Joe Biden talk about what he's calling middle-out economics, and some people even

use the term bottom-up economics as opposed to the failed policies

of top-down or trickle-down

economics.

What ITEP seems to be suggesting is that states can align

themselves with these ideas by improving the status of lower-income and

middle-income people by shifting some of the burden to the highest-income

earners. In this way, we can get to a more fair tax system and also maybe do

good things for the economy as a whole. Does that make sense? And does that

make sense in the current political climate?

Alan Krinsky: I don't know that I can speak to the

political climate in Washington, but it makes sense. One of the interesting

things in the ITEP report is that it demonstrates a correlation between the

progressivity of the tax system and the amount of revenue that's raised. When

the tax system is more progressive overall, you're raising more revenue and

providing more and better services. What you're talking about, from a national

perspective, fits in with that model.

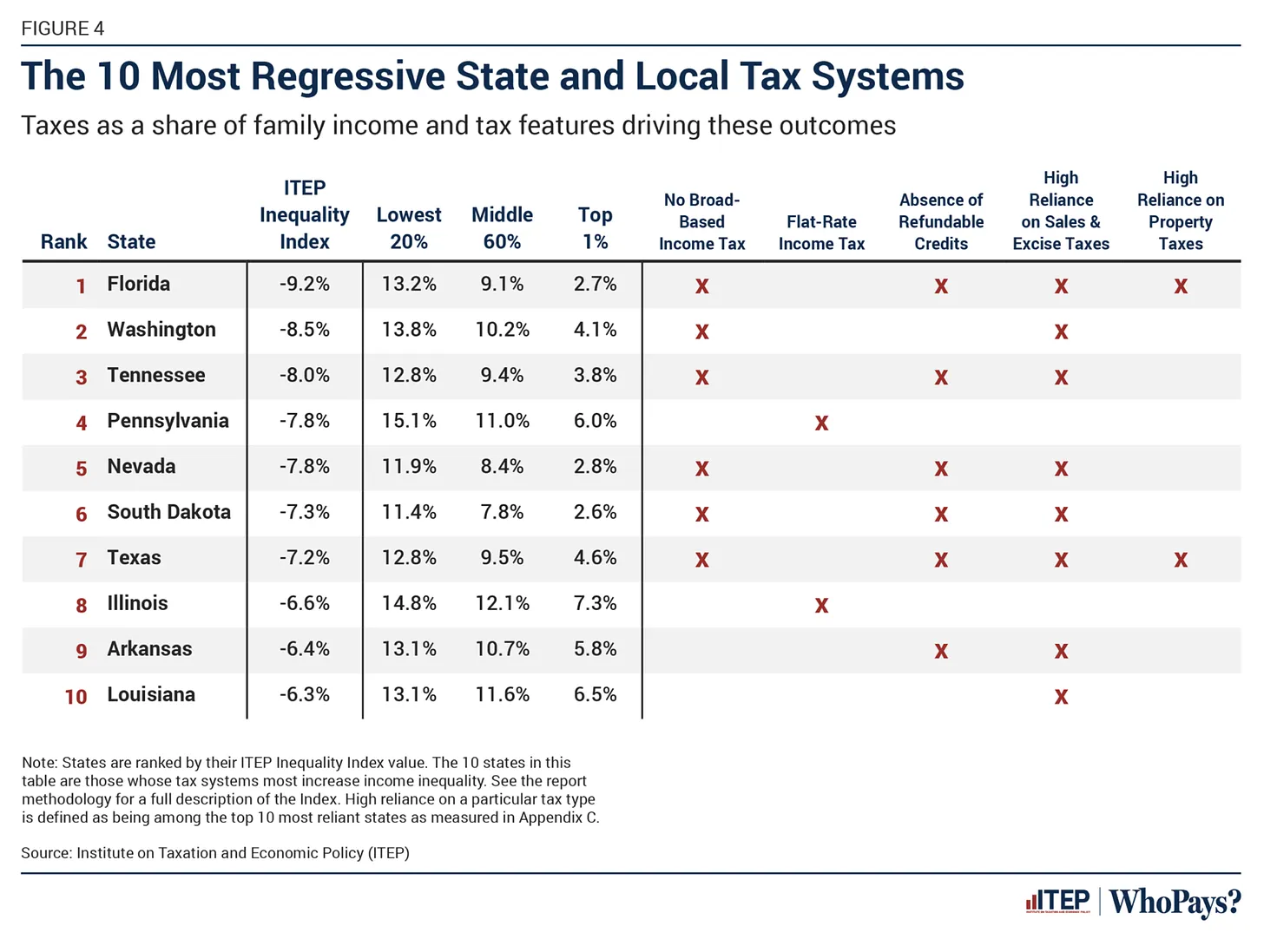

Another thing I'll point out: Even though Rhode Island

ranks 31 out of 50 states overall for our regressive tax system, we are one of

the 10 worst states for the lowest income group, the bottom 20%.

Steve Ahlquist: So basically you're saying that the

people in the lowest quintile are being hit harder than the data might suggest

by our 31st place ranking.

Looking at the following chart, you can see Rhode Island

taxes its poorest 20 percent of earners at rates greater than Florida,

Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas.