Has past funding been distributed fairly?

By Nancy Lavin, Rhode Island Current

It doesn’t matter who hears the tree that falls in the forest if the forest has already been razed for development or ravaged by brush fires.

Which is why environmental advocates and lawmakers are rallying behind a proposal to borrow $16 million for state land preservation — before it’s too late.

“Once farmland is gone, it’s gone,” said Sen. Lou DiPalma, a Middletown Democrat. “You can’t get that back.”

DiPalma and Rep. Megan Cotter, an Exeter Democrat, introduced legislation earlier this month to add $16 million for land protection programs to the existing, $50 million “green economy” bond included in Gov. Dan McKee’s fiscal 2025 budget proposal.

The extra money would replenish depleted grant programs that preserve open space, forest and farmland, which might otherwise be sold for commercial development or cleared to make way for massive solar arrays. There is also money for forest management and habitat restoration.

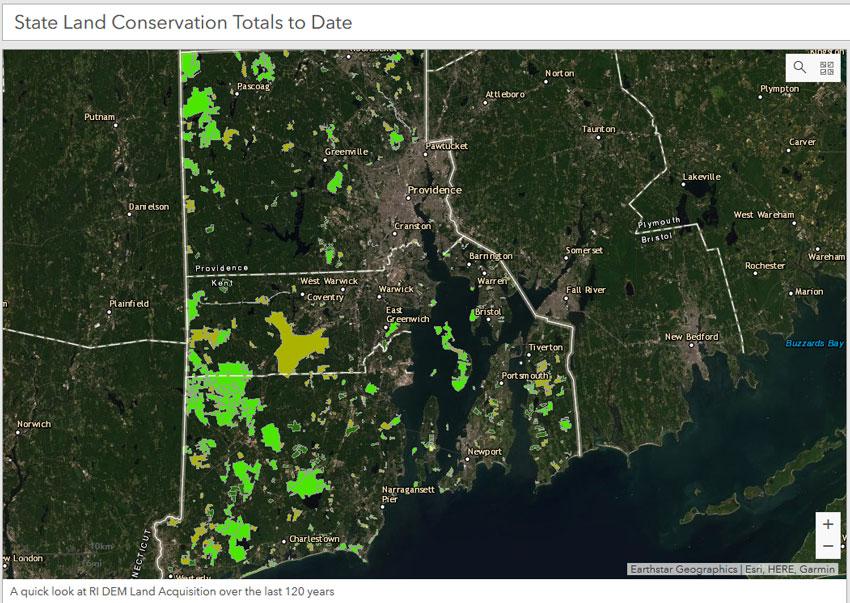

3233.8766 acres in Charlestown alone:

|

| DEM Land Aquisition report. These figures DO NOT include open space where state funding was not a factor, such as lands owned by the federal government, the Narragansett Indian Tribe, private non-profits, the Town of Charlestown or its two "fake" fire districts (Central Quonnie and Shady Harbor). |

Land protection and acquisition programs have been a centerpiece of state “green” bonds for decades, included in borrowing proposals for all but four of the last 22 election cycles since 1988, according to data provided by DEM.

State budget officers said the total $345 million in borrowing (including three other proposed ballot questions) equals the debt coming off the state’s books over the next two years.

“The question then became how to best allocate the $345 million across a whole range of needs,” Olivia DaRocha, a spokesperson for McKee’s office, said in an emailed statement. “The governor prioritized economic growth in all four bonds, and the Green Economy Bond items were chosen for their economic growth impact and investment in existing facilities.”

‘Surprised, to say the least’

Kate Sayles, executive director for the Rhode Island Land Trust Council, was shocked at the lack of funding for open space protection in McKee’s proposed budget, having sat in on discussions with top state leaders about the need for state bonding to access federal and nonprofit matching dollars.

“We were surprised, to say the least, that there was zero dollars included,” Sayles said.

The DEM in its fiscal 2025 budget request to the governor’s office also asked for $16 million in bonds for forest and farmland protection, though the split between programs was slightly different than what DiPalma’s and Cotter’s legislation sets forth.

DEM spokesperson Michael Healey said in an emailed statement, “We appreciate the pressures and constraints that came with the submittal of the FY 25 budget. As an executive agency that is very mindful of the separation of powers doctrine, DEM will implement whatever the budget ultimately directs us to implement.”

Others were less diplomatic.

“The money is there; they can borrow more money and they are making a choice not to,” said Phoenix Wheeler, advocacy director for Audubon Society of Rhode Island. “It’s a matter of being willing to do it, or not. We should prioritize safe and healthy lives for all Rhode Islanders.”

Cotter suggested money could be shaved off of the other potential bond items, such as the infrastructure improvements at Quonset.

“This $16 million is non-negotiable,” Cotter said. “We need it. Rhode Island cannot afford to lose any more of its forests.”

She would know, having watched a massive wildfire scorch 400 acres of land in her native Exeter in April 2023 — the largest wildfire in state history since 1942, state officials said. The $3 million proposed for forest management would help DEM with upkeep and wildlife restoration on state-owned forest land, including reforestation and prevention against increasing threats of wildfires.

Another $5 million would restore DEM’s open space grant program to its historic levels, while $3 million would center on municipal-led open space protection programs.

The final, $5 million chunk would replenish depleted funds in the state Farmland Preservation Program, which is run by the quasi-public Agricultural Land Preservation Committee.

Since 1985, the committee has spent more than $106 million — including $38.2 million of state bond funding — to buy development rights that protect more than 8,200 acres of farmland across the state, according to DEM.

The last state bond that included money for the program was in 2021, when $3 million was approved by voters. But the list of farmers looking to sell their development rights to the state keeps getting longer, and the program found itself nearly out of money last year, with just $300,000 in uncommitted funds.

The Rhode Island General Assembly included $2.5 million in its fiscal 2024 spending plan as a stopgap measure, but already, much of that money has been spent or committed, leaving the program with about $1.8 million available, said Diane Lynch, a committee member who is also president of the Rhode Island Food Policy Council.

Long list of interested farmers

Meanwhile, the committee is staring down a 50-applicant waiting list of farmers “in the queue” for state development agreements, according to Lynch, who declined to share the list due to confidentiality. Another $5 million in state bonding, combined with available federal and nonprofit funding, would cover the cost to preserve 15 of the “highest priority” farms, equal to about 1,000 acres, Lynch said.

The alternative of waiting another two years for the 2026 bonding cycle is not an option in her view, as farmers’ profit margins shrink and the temptation to sell to developers mounts. Waiting also puts the state at risk of missing out on available federal funding, since the federal programs that fund conservation require some level of local match.

“Leaving federal dollars on the table is never a good idea,” Lynch said.

It’s not just farmers, or environmental advocates, who benefit from the program, either.

Protection means more open space for public access, while carbon reduction from trees is crucial to meeting the state decarbonization mandates under the 2021 Act on Climate Law.

Also not to be discounted: the economic benefits. The state’s agricultural industry generated $100 million in transactions in 2021, with production and processing equal to 1.2% of the state GDP, according to the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture.

A separate study by regional conservation nonprofit Highstead found that every dollar of state funding spent on land conservation generates $4 to $11 in economic value.

Not that voters appear to need convincing. Green bonds that include open space and land acquisition have received strong support in past elections.

Preliminary results of a January poll by The Nature Conservancy also reveal that 75% of the 400 likely voters surveyed would “definitely” or “probably” approve of an even larger green bond: $75 million, with money for open space and farmland acquisition.

Voters were no more enthusiastic when propositioned with smaller borrowing amounts, according to preliminary poll results, suggesting that support for a larger green bond exists, said Sue AnderBois, director of climate and government relations for The Nature Conservancy in Rhode Island.

But before voters get a potential say, the proposal must pass muster with lawmakers to even make it to the ballot. DiPalma agreed with McKee’s emphasis on responsible borrowing, but said he wanted more information on what was in the “realm of possibility” for state debt service.

House Speaker K. Joseph Shekarchi expressed interest in the proposal in an emailed statement:

“If the revenue estimates following the May conference are solid, my intention is to work with the House Finance Committee, the Senate and the Governor to increase the amount of the green bond to be placed on the November ballot. I would especially like to enhance the investment in open space and farmland preservation.”

Senate President Dominick Ruggerio in an emailed statement also said open space and farm preservation is an important issue to state senators.

“In the weeks ahead, as the budget review process continues and the state’s financial picture comes into clearer focus, we will explore available avenues to invest in this area, including through an increase in the green bond proposal,” Ruggerio said.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX

Rhode Island Current is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Rhode Island Current maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Janine L. Weisman for questions: info@rhodeislandcurrent.com. Follow Rhode Island Current on Facebook and Twitter.