Carlson marveled at the fancy tilework of the

city’s subway system, visited the national ballet, and noted

that you can buy caviar cheaply

at the local grocery store. He also pointed out that Moscow’s pristine streets had no homeless people and no

apparent poverty.

In the gilded halls of the Kremlin palace, he interviewed President

Putin for more than two hours. Despite his guileless expression, Carlson

occasionally appeared flummoxed as Putin lectured him endlessly on Russian

history and the centuries-old claim he insisted Moscow has on Kyiv as its

protector from aggressors near and far.

Of course, he never challenged Putin on

his rationale for invading that country (nor did he refer to it as an invasion)

or any of the Russian leader’s other outrageous claims.

I’m of the school of thought that considers Putin’s

Russia exactly the sort of anti-woke paradise the

MAGA crowd craves. Anyone of Carlson’s age who grew up during the Cold War and

turned on his or her television in that pivotal period when the Berlin

Wall fell should certainly know that all of

Russia doesn’t look anything like what he was shown.

He should also have known

about the recent history of economic “shock therapy” that

drained Russian public services of funding and human resources, not to speak of

the decades of corruption and

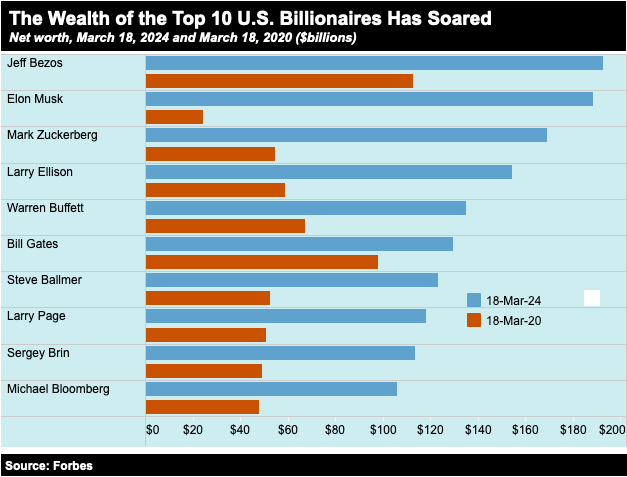

unfair economic policies that enriched a choice few in Putin’s circle at the

expense of so many.

Of course, something had to happen to turn the Moscow

that Carlson saw into a sanitized moonscape. If you haven’t been following

developments in Russia under Putin, let me summarize what I’ve noticed.

Protesters —

even many going to

opposition leader Alexei Navalny’s recent memorial service — have been arrested

or at least intimidated when appearing to sympathize with anything that’s not

part of the Kremlin’s official pro-Putin ideology. Many groups, from

Asian migrants to

the homeless, have either

been rounded up by the police or at least relocated far out of the view of

tourists of any sort.

In fact, the imprisoned American journalist whom Carlson

briefly gestured toward emancipating, Wall Street Journal reporter

Evan Gershkovich, had written on the practice of zachistki, or

mop-up operations by the Russian authorities that, for instance, relocated

homeless services to the outskirts of Moscow, far from public view.

Of course,

Gershkovich is now imprisoned indefinitely in Russia on

charges of espionage for simply reporting on the war in Ukraine, proving the

very point Carlson so studiously avoided, that an endless string of lies

underscore Putin’s latest war.

What’s more, amid sub-subsistence wages, housing

shortages, and the thin walls of so many city apartments, ordinary Russians are

not always able to engage in the “hard conversations” that conservatives like

Alabama Senator Katie Britt boast of having in their well-furbished kitchens.

After all, neighbors are now encouraged to denounce each other for decrying

Russia’s war. (You could, it seems, even

end up in prison if your child writes “no to war” on a drawing she did for

school.)

There are very personal ramifications to living in an

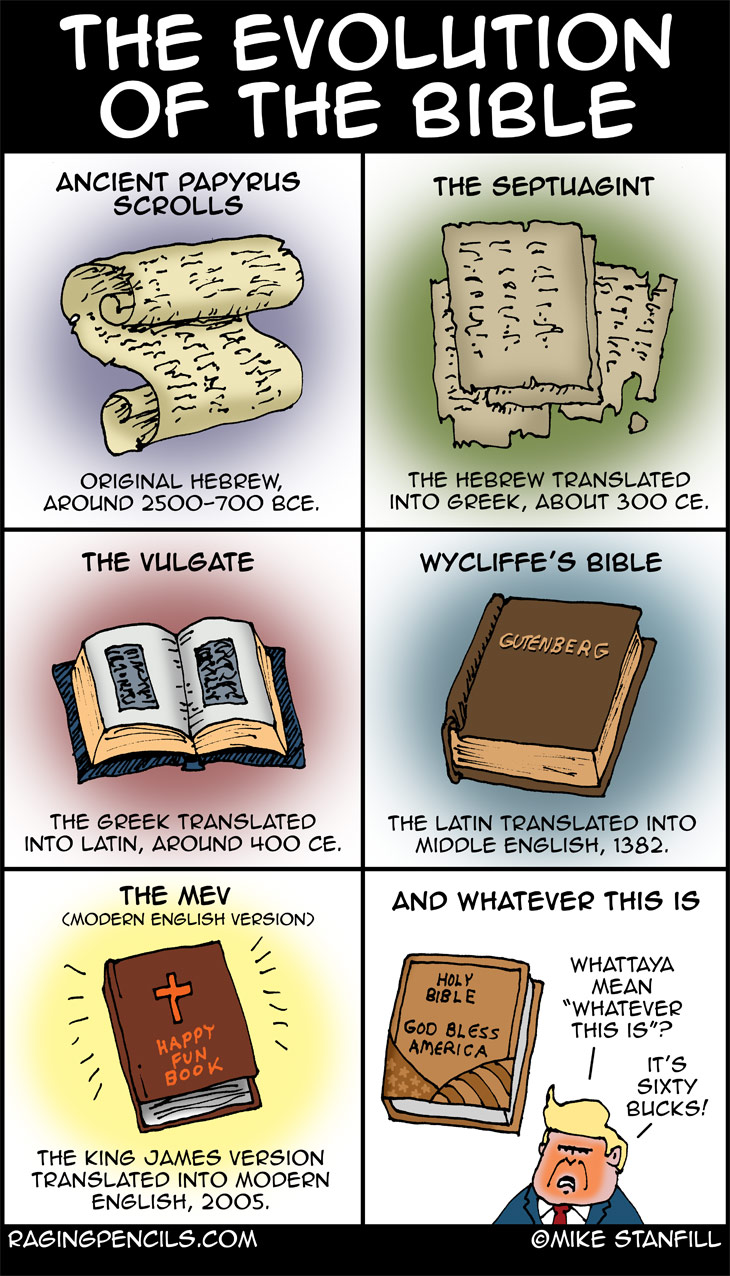

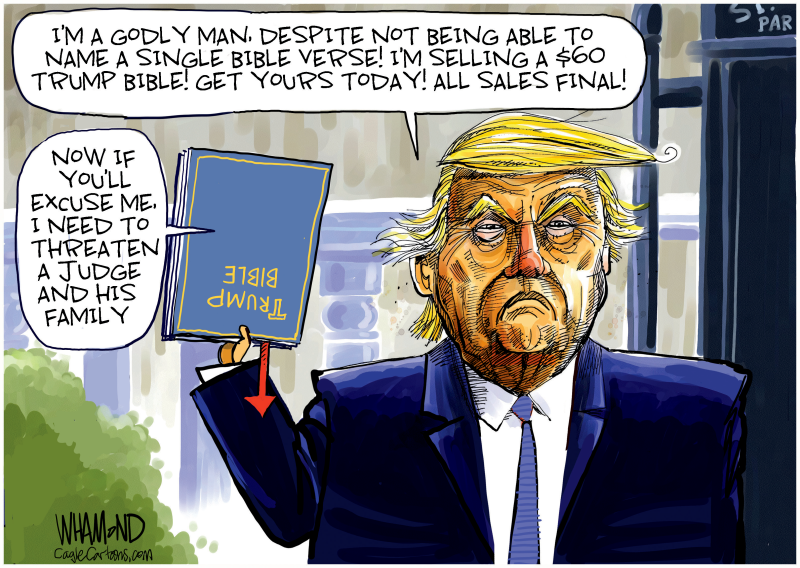

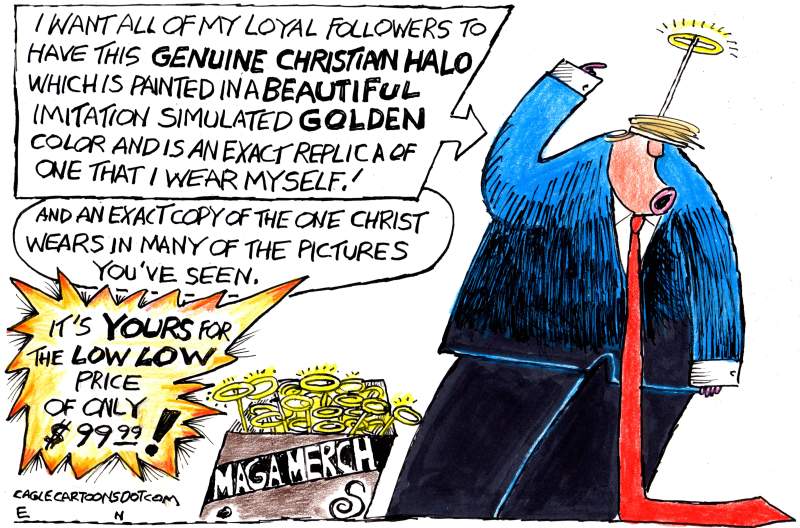

autocracy with which Tucker Carlson and, of course, the Orange Jesus himself

are signaling their agreement when they entertain the views of leaders like

Vladimir Putin or call Hungarian

autocrat Viktor Orbán “fantastic.” They’re signaling what their end goal is to

Americans and, sadly enough, it’s not particularly far-fetched anymore to

suggest that, someday, we won’t even have the freedom to talk about all of this

with each other.

The Thing That Cannot Be Named

Tucker Carlson at least did his homework. He clearly knew

that you couldn’t describe the war in Ukraine as an unprovoked Russian

invasion, given that country’s carefully crafted censorship laws.

Since his February 2022 invasion, Putin has referred to

it as a “special military operation” focused on the defense of Russia from NATO

and the “denazification” of Ukraine.

During that first spring, the Russian

president signed a law forbidding journalists from even calling the invasion a

“war,” choosing

instead to frame the killing, displacement, abduction, torture, and rape of

Ukrainian citizens as a surgical rescue operation provoked by the victims

themselves.

Broader, vaguer censorship laws were then passed, further limiting

what Russians of all stripes could say, including one against “discrediting the army,”

which imposed stiff fines and prison sentences, and more recently, property confiscations on

anyone deemed to have said anything negative about Russia’s armed forces. While

the thousands of

arrests made may seem modest, given Russia’s 146 million people, it’s still, in

my opinion, thousands too many.

The Russian leader’s perverse framing of his unprovoked

war is undoubtedly what also allows him to admit that

hundreds of thousands of Russians have been killed or wounded so far, something

he couldn’t otherwise say. In a country suffused with right-wing Christian

nationalism, it also certainly helps his cause that most of Russia’s

war dead come from remote, poor, and predominantly minority regions.

This is the sort of muddling of meaning and motives that

autocratic leaders engage in to justify deaths of all kinds. American

equivalents might be what the MAGA crowds do when they blame the January 6th

far-right assault at the Capitol, aimed at police and lawmakers, on the “Antifa,” or extreme

leftists, without disputing that people were hurt.

Or consider then-President

Donald Trump’s comment that far-right white supremacist Charlottesville rioters

and counter-protesters included “very fine people on both sides”

— no matter that one such fine person plowed down a

counter-protester in his car, murdering her, or that certain of those “fine”

white supremacists espoused anti-Semitic conspiracy theories considered by some an

incitement to violence.

For their part, Russians of various political stripes

enjoy an ancient tradition of using dark humor and irony to engage in the kinds

of conversations they really want to have. Take as an example the way

progressive journalists like those at the news stations TV Rain and Novaya

Gazeta (since banned from operating) began discussing the

war in Ukraine as “the thing that cannot be named.” Eventually, however,

sweeping censorship laws prevented even workarounds like those.

It’s not a small thing to live in a place where you can’t

say what you want to for fear of political persecution, especially when you’ve

grown up in other circumstances. A good friend of mine who came of age after

the fall of the Berlin Wall and led a prosperous, happy life in St. Petersburg,

fled the country on the last train out of that city to Helsinki, Finland, her

young child in tow.

Her goal: to start life over from scratch and avoid having

to raise her child in a place where he would be brainwashed into thinking

Russia’s armed forces and police were infallible and beyond critique. I suspect

that many of the hundreds of thousands of

Russians who joined her in fleeing the country weren’t that different.

Imagine raising a child whose unquestioning mind you

can’t recognize. (That goes for you, too, Trump supporters, because — count on

it! — once in office again, he would undoubtedly move toward ending elections

as we know them, not to speak of shutting down whatever institutions protect

our speech!)

America and the Lie that Begot Other Lies

Events in recent years indicate that Americans —

particularly those in the MAGA camp — have grown inured to the public mention

of armed violence. Who could forget the moment in 2016 when candidate

Trump boasted at a

campaign rally before winning the presidency that “I could stand in the middle

of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose voters”? As racially and

politically motivated violence and threats have proliferated, so many of us

seemed to grow ever less bothered by both the incidents themselves and the

rationales of those who seek to encourage and justify them.

My own adult life began as Vladimir Putin consolidated

power in Russia, while former President George W. Bush launched his — really,

our — disastrous Global War on Terror, based on lies like that Iraqi leader

Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction.

Unfortunately, we’ve

spilled all too little ink here on the nearly one million people who

died across our Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African war zones since 2001

(and the many millions more who

lost their lives, even if less directly, or were turned into refugees thanks

to those wars of ours).

And don’t forget the more than 7,000 American troops (and

more than 8,000 contractors!) who died in the process, essentially baptizing

our national lies in pools of blood. And how could that not have helped

normalize other lies to come like Trump’s giant one about the 2020 election?

Thankfully, in this country we can still say what we want

(more or less). We can still, for instance, call out the Pentagon for underreporting the

deaths its forces have caused. In other words, something like the Costs of War Project that I helped

to found to put our lies in context can still exist. But how long before such

things could become punishable, if not by law, then through vigilantism?

Yes, President Biden is arming Israel in its gruesome

fight against Hamas while providing only the most modest aid to Gaza’s

war-devastated population, but we can still hold him to account for that. If

the 2024 election goes to Donald Trump, how long will that be true?

If we don’t

get to the point right now where all of us are calling out lies all the time,

then every Trumpian lie about violence — from Republican members of Congress

calling the January 6th rioters “peaceful patriots” to The Donald’s claim that

he would only be a dictator on “day one” of his next presidency (a desire

supported by a significant majority of Republicans) — will amount to lies as

consequential as the 1933 burning of the Reichstag parliament building in

Germany, which Hitler’s ascendant Nazi party attributed to communists, setting

the stage for him to claim sweeping powers.

We are entering a new and perilous American world and

it’s important to grasp that fact. In that context, let me mention a Russian

moment when I did no such thing.

I still feel guilty about a dinner I had with

human-rights colleagues in 2014, including a Russian activist who had dedicated

his career to documenting political violence and war crimes committed under

successive Russian leaders from Joseph Stalin to Vladimir Putin.

I was sitting

at the far end of the table where I couldn’t catch much of the conversation and

I joked that I was “out in Siberia.” Yes, my dinner companions graciously

laughed, but with an undercurrent of discomfort and tension — and for good

reason.

They knew the dangerous world they were in and, in fact, that very

activist has since been sent to a penal colony for his work discrediting the

actions of the Russian armed forces. My joke is anything but a joke now and

consider that a reminder of how quickly things can change — and not just in

Russia, either.

In fact, oppression feels closer than ever in America

today and verbal massaging, joking, or willful ignorance can only mask what

another Trump presidency could mean for us all.

© 2023 TomDispatch.com

ANDREA MAZZARINO Andrea Mazzarino co-founded Brown University's Costs of

War Project. She is an activist and social worker interested in the health

impacts of war. She has held various clinical, research, and advocacy

positions, including at a Veterans Affairs PTSD Outpatient Clinic, with Human

Rights Watch, and at a community mental health agency. She is the co-editor of

"War and Health: The Medical Consequences of the Wars in Iraq and

Afghanistan" (2019).

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)