What is chemical recycling?

Hannah Seo for Environmental Health News

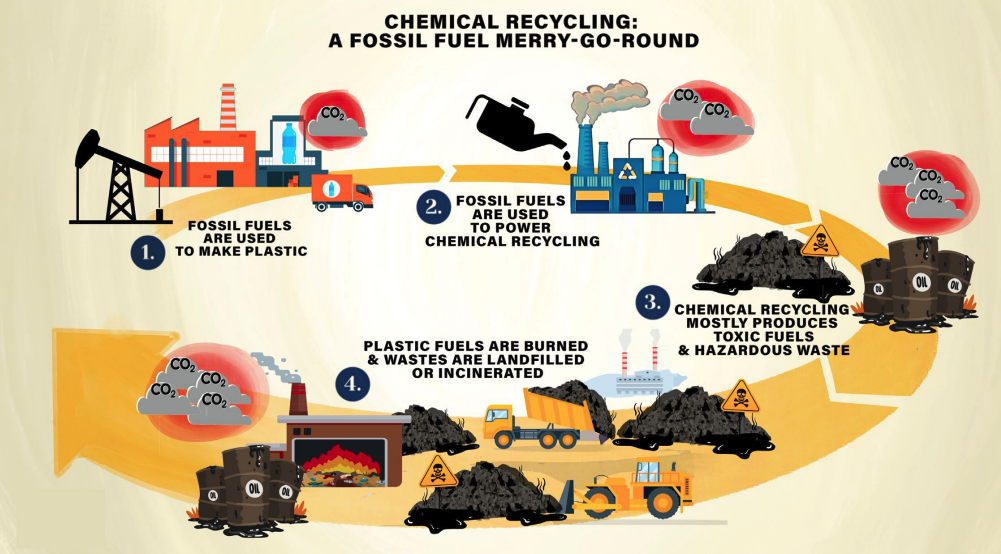

(Beyond Plastics and IPEN, 2023)

When you think about plastic recycling, you probably

picture plastic being converted into shiny new bottles, boxes and bags.

But industry players and proponents are now pushing for

“chemical recycling”, claiming it could be an effective way to keep plastic

waste out of landfills and oceans.

Here’s everything you know to know about the practice.

What is chemical recycling?

Chemical recycling is a set of technological processes that

have been around for decades. There are three broad methods used in chemical

recycling:

·

Conversion: Extreme heat helps convert

plastic waste into either a synthetic crude oil via pyrolysis, or synthetic gas

via gasification.

·

Decomposition: Heat or chemicals break

plastic polymers into their smallest parts.

·

Purification: Strong solvents separate

plastic polymers from contaminants.

The crude oil — also called syngas — created from

conversion can be refined into diesel fuel, gasoline and other products. When

polymers are broken down and collected, they can theoretically be used to

create new plastic products.

Why is chemical recycling controversial?

“Chemical recycling is really an industry ploy to convince

the public and policymakers that we don't have to reduce plastic production in

order to deal with plastic waste,” Jennifer Congdon, deputy director of the

environmental advocacy group Beyond Plastics, told EHN (EHN).

The phrase “chemical recycling” suggests that these processes can result in new plastic products made from old plastic. But most of the plastic waste that goes through chemical recycling fails to become anything usable, Congdon said.

In a 2023 report, Beyond Plastics, in collaboration with the International Pollutants Elimination Network, wrote that when using pyrolysis, only 20 to 30 percent of plastic waste input becomes extractable polymers.

This means that “up to 80 percent of

the plastic waste going in for recycling is actually lost as process fuel,

emissions or becomes hazardous waste,” the report says.

Another report from the Natural Resources Defense Council calls chemical recycling the plastic industry’s attempt at “greenwashing incineration.” Burning synthetic oil or syngas that come out of chemical recycling is essentially just another, complicated way to burn fossil fuels.

Chemical recycling processes are energy-intensive, emit greenhouse

gasses and toxic pollutants, but “offers none of the ecological or economic

benefits of true recycling,” the report says.

“The thinking that we can continue to use plastics at the

rate that we're using them, and then deal with the waste by turning it into

fuel and then burning it, is really collective madness,” said Congdon. “This

stuff is so dirty and so toxic. It's not a solution.”

What are the pollution concerns and health risks from

chemical recycling?

The pollution and health concerns that come with chemical recycling are essentially the same as those that come with plastic production.

Chemical recycling facilities also emit toxic pollutants like benzene, toluene, dioxins, heavy metals and PFAS—all of which have been linked to serious health concerns like cancer, hormonal disruption and reproductive and developmental damage.

Subproducts of plastic recycling, like plastics-based jet fuel, have also been

linked to cancer in as many as one in every four people with a lifetime

exposure, according to the U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

The plants also produce non-trivial volumes of hazardous or

corrosive waste.

The Beyond Plastics report states that in 2019, a chemical

recycling plant in Oregon sent data to the EPA showing that it incinerated 283

tons of hazardous waste. This same facility produces one ton of hazardous waste

for every three tons of plastic waste that they process.

When you factor all this together, it’s actually safer for

the environment to landfill plastics than it is to chemically recycle them,

Congdon said. So despite the enormous and unwieldy amounts of plastic waste out

there (and more being generated all the time) chemical recycling is not the

answer. “We really have to focus on reduction strategies” and lower the amount

of plastic being produced, she said.

Who is most at risk from chemical recycling

pollution?

As of September 2023, there are 11 chemical recycling

facilities in the United States, according to the 2023 Beyond Plastics report.

Oregon, Nevada, New Hampshire, Indiana, Tennessee, North Carolina and Georgia

each have one chemical recycling plant. Texas and Ohio have two each.

Chemical recycling facilities in the U.S., like other

plastics plants, are mostly located in low income communities and communities

of color, said Congdon. “This is absolutely an environmental justice concern.”

In their 2023 report, Beyond Plastics analyzed the

five-mile ring of land around 11 chemical recycling plants. They found that

“eight of the plants are located in areas with lower-than-average levels of

income, compared to the national average; and five have higher-than-average

concentrations of people of color than the rest of the country.”

Interestingly, many of the factories “are not operating or

not operating at capacity,” Congdon said. Even so, “the industry is looking to

build more of them.” But even if they were operating at full capacity, these

facilities would be processing a very small percentage of our annually produced

plastic waste, while generating a lot of hazardous waste, she added.

What does industry say about chemical recycling?

Proponents of chemical recycling point to the possibility

of a more “circular

economy”, describing a world where more and more plastic waste is

funneled continually into new products.

Industry leaders say the practice will help fix the problem

of plastic waste — most of which cannot be recycled mechanically.

But while the industry tries to frame chemical recycling as

a way to extend the life of plastics, “we reject that and do not believe it is

a tool that should be in any proverbial toolbox,” Daniel Rosenberg, senior

attorney and director of federal toxics policy at NRDC, told EHN.

“The American Chemistry Council has also been working to

get chemical recycling reclassified as manufacturing instead of as waste

processing” on a federal level, Congdon said. This move would weaken the

scrutiny for its hazardous emissions and waste.

Its recent petition to the EPA for this reclassification

got rejected, she added—rightly so, since these facilities often can’t prove

that they’re actually creating a valuable product for the market. But had that

petition been successful, the plastics industry would suddenly be eligible for

a number of subsidies and incentives that could have led to a surge of chemical

recycling.

What chemical recycling regulations exist in the US?

The EPA ruled last year that chemical recycling processes need to be regulated under the Clean Air Act. However, prior to that ruling, 24 states have already passed individual laws reclassifying chemical recycling processes as manufacturing.

What remains to be seen is whether the EPA will step in and tell those states

that they must regulate chemical recycling as waste processing as part of a

national standard, Congdon said.

The ability for industry players to go full steam on chemical recycling depends on them being able to get out from under federal pollution controls, Rosenberg said. This includes “monitoring their emissions, reporting their emissions, limiting their emissions, restrictions on how they dispose of waste.”

All of this should be seen as evidence that “these proposals

are not actually good for public health or the environment, particularly for

environmental justice communities.”

Several lawmakers do seem to recognize and understand the

pitfalls of the practice. In July of 2023, the U.S. House Appropriations

Committee wrote in a report that

it “encourages” the EPA to maintain regulating chemical recycling technologies

as municipal waste combustion units under the Clean Air Act.

What role will chemical recycling have in the Global

Plastics Treaty?

The Global Plastics Treaty is part of a resolution by the United Nations Environment Programme to develop an international and legally-binding agreement to end plastic pollution.

Ideally, the treaty would

force plastic manufacturers to address the full life cycle of plastic, from its

production to its disposal. The next session will be held in Ottawa in April.

Some experts fear that chemical recycling ends up being incentivized in the treaty. A coalition of Saudi Arabia, Russia, Iran, Cuba, China and Bahrain are pushing to focus on plastic waste rather than production limits.

But promoting chemical

recycling “would be the worst outcome the Treaty could endorse for managing

plastic waste,” wrote 20 scientists in

November of 2023.

Many unknowns remain regarding the stance the U.S. government will take in global negotiations about plastics, Rosenberg says. Whether we’ll start to see plastic production caps, for example, is still up in the air.

Groups like NRDC are also looking to see whether the EPA will roll

back its prior approvals for some toxic chemicals derived from plastic waste as

per the Toxic Substances Control Act. All of this is consequential for how

chemical recycling will be regulated in the U.S.

None of these are currently set in stone, said Rosenberg,

but it will be significant to see what position the U.S. takes.

Where can I learn more about chemical recycling?

Various organizations have a number of reports and

fact-sheets where you can learn more about chemical recycling.

·

In addition to their 2023 report in

collaboration with IPEN, Beyond Plastics has a fact-sheet breaking

down the pitfalls of chemical recycling.

·

NRDC has an introduction to

chemical recycling, as well as a longer

breakdown of its harms to the environment.

·

U.S. Public Interest Research Groups

has published an explainer from

Beyond Plastics on the basics of chemical recycling.

·

The Global Alliance for Incinerator

Alternatives conducted a large investigation on chemical recycling, which they

published in this 2020 report.

·

Greenpeace published a 2020

analysis on why claims about chemical recycling as an economic

good fail to hold up to scrutiny.

And follow EHN’ continuing coverage of chemical recycling

and plastics here:

Sign up for our free daily newsletter, Above the Fold,

featuring the most consequential news on our environment and health.

Hannah Seo is a science journalist, essayist,

podcast writer, and poet based in Brooklyn.