Another shellfish friend of the environment

By Frank Carini /

ecoRI News staff

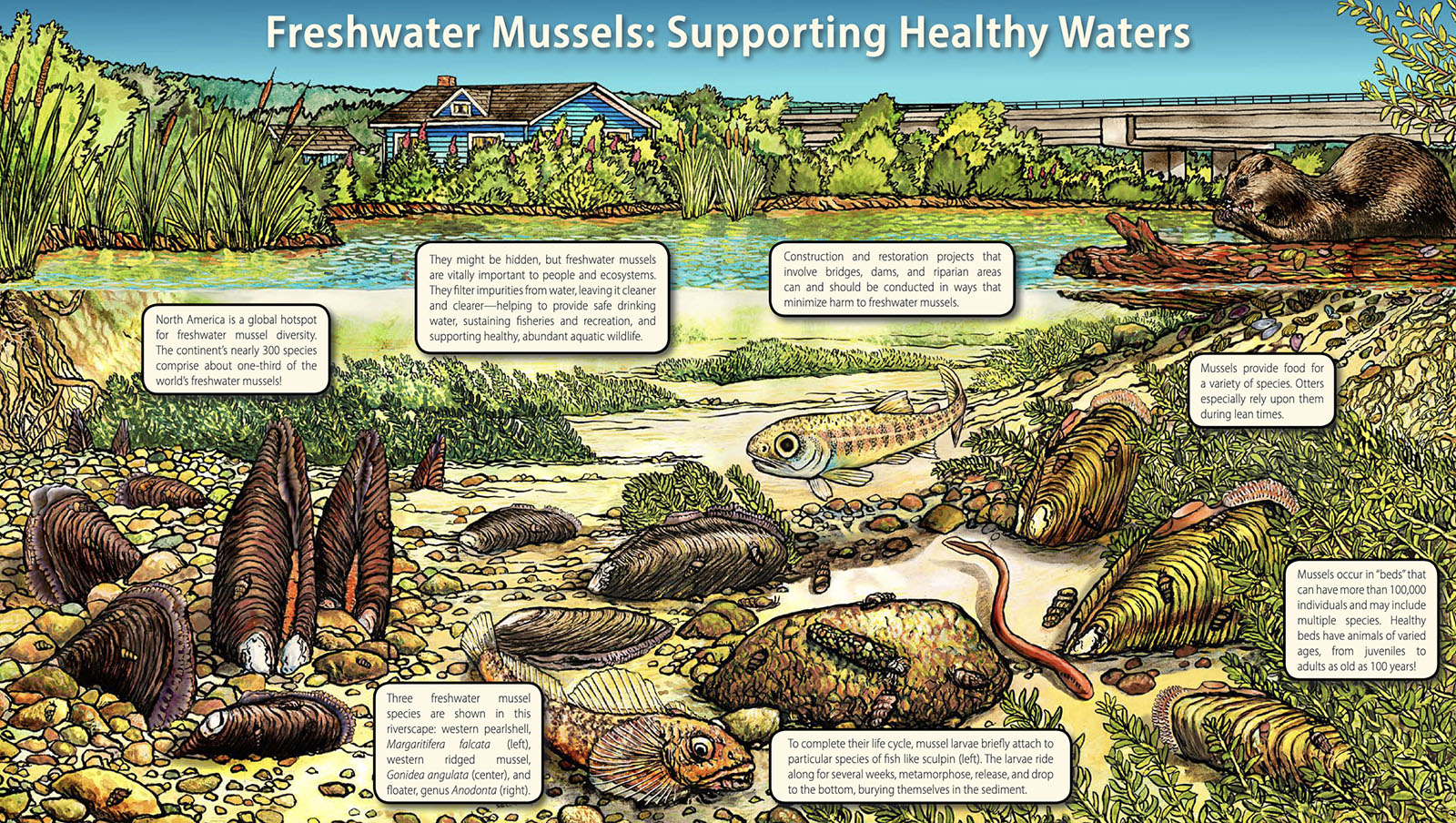

Freshwater mussels play a vital role in supporting stream, river, and lake ecosystems. (Xerces Society)

Freshwater mussels breathe rivers clean.

They are also sensitive to changes in the environment, which puts them at

substantial risk. They and the habitat they require are disappearing at a

disconcerting rate.

Their presence in lakes and ponds are

indicative of high water quality. Their absence tells a different story. The

latter is the more-familiar tale.

Rhode Island’s populations of mussels have

been degraded by a long history of damming and pollution discharges into

rivers. Lake populations have largely been eliminated by basin

reconfigurations, pollution, and urban development, according to a 2006 study.

Between 1980 and 2006, Christopher Raithel and Raymond Hartenstine inventoried freshwater mussel populations at 129 sites throughout Rhode Island. They found eight native mussel species: eastern elliptio (Elliptio complanata); eastern floater (Pyganodon cataracta); triangle floater (Alasmidonta undulata); alewife floater (Anodonta implicata); eastern lampmussel (Lampsilis radiata); eastern pondmussel (Ligumia nasuta); eastern pearlshell (Margaritifera margaritifera); and squawfoot (Strophitus undulatus).

The researchers also discovered the state’s

populations of freshwater mussels are facing significant threats. They “are

rare or localized and should be considered high conservation priorities in

Rhode Island,” the co-authors wrote in their study.

The introduction of “The Status of

Freshwater Mussels in Rhode Island” noted North America contains a high

proportion of the world’s freshwater mussels, but “several mussel extinctions

have already occurred and many other species are imperiled.”

Corey Pelletier, a fisheries biologist for

the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management stationed at the Great

Swamp Management Area, said those eight species remain in Rhode Island, but he

noted “there are certain species that have very localized distributions and are

at higher risk of extirpation.”

In fact, six of the state’s freshwater

mussel species are species of greatest conservation need, according to

Pelletier. Those species are the triangle floater, alewife floater, eastern

lampmussel, eastern pondmussel, eastern pearlshell, and the squawfoot.

He said freshwater mussels are “one of the

most imperiled group of animals in the United States” and noted many of these

species are indicators of water quality and ecosystem health.

“Pollution in the form of roadway runoff,

agricultural runoff, and other chemicals and metals that are discharged into

waterways are the primary threats to freshwater mussels,” Pelletier wrote in a

recent email to ecoRI News.

He also noted that freshwater mussels rely

on specific host fish species for reproduction. Mussel species that require

specific hosts, such as wild brook trout and river herring, “may be at risk due

to declines or limitations of these species”

“Few freshwater mussel surveys have been

completed in recent years,” he said “The Division of Fish and Wildlife hopes to

be able to utilize eDNA in the future to better understand and document species

distributions.”

There are nearly 300 native freshwater

mussel species in North America, compared to 12 in Europe, according the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

Of those, about 70% are in decline, 40% are listed as threatened, 21% are

listed as endangered, and 7% are extinct.

Their numbers took a beating in the early

1900s when big-river dam-building exploded. Thousands of river miles were

flooded, the flow of water slowed, and river bottoms were buried in layers of

muck. Mussels, which need to siphon moving water to breathe, suffocated.

Their populations haven’t really recovered,

which is too bad for anglers, hunters, birdwatchers, wildlife enthusiasts, and

conservationists. Healthy mussel populations typically indicate a healthy

aquatic system, which usually means good fishing and good water quality for

waterfowl and other wildlife species.

But the remaining pockets of healthy

freshwater mussel populations are under an increasing amount of stress.

The Xerces Society for Invertebrate

Conservation has noted “destruction of habitat has been one of

the biggest impacts to freshwater mussels, including the construction of dams

that have altered how rivers flow and function.

The Portland, Ore.-based nonprofit has also

noted water diversions for human uses that decrease streamflow, combined with

warming waters and changing precipitation patterns, have and will continue to

threaten mussel populations.

“Pollution and toxic chemicals also impact

mussels, which can be especially sensitive to certain contaminants,” according

to the Xerces Society. “The same characteristics that have made them so

valuable to protecting our water quality (sedentary nature, ability to reach

high density, and filtering lifestyle) also make them vulnerable to a wide

range of stressors to which they may ultimately succumb.”

Freshwater mussels are members of a large

group of animals called mollusks, which includes saltwater mussels, clams,

snails, squid, slugs, and octopuses. They are part of the benthos, which is the

community of fauna and flora that occupies the bottom of a waterbody.

Mussels play many important roles in

freshwater ecosystems, especially in cool, flowing streams. They feed by

filtering water through their siphons. In fact, they are one of nature’s

greatest natural filtration systems. Not only do they stabilize freshwater

ecosystems, but they also continually protect and improve water quality. A

single mussel can filter 5-10 gallons of water a day.

They also filter algae out of water, but

may filter at a slower rate if the water is dominated by toxic blue green algae

(cyanobacteria), according to a 2013 paper published

by the University of Rhode Island.

Cyanobacteria is a growing problem in Rhode

Island and throughout southern New England because of warming air and water

temperatures and the proliferation of fertilizer containing nutrients such as

nitrogen and phosphorus.

“Mussels consume zooplankton, detritus

(dead and decaying matter), and algae. Therefore, they help maintain the proper

balance of organisms typical of waterbodies that are oligotrophic or

mesotrophic (have a low or medium level of nutrients),” the authors of the

four-page paper wrote. “The mussels themselves serve as a food source for fish

and other wildlife [such as river otters].”

For more information about the importance

and vulnerability of freshwater mussels, click here for a

collection of U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service webinars.

Note: Christopher Raithel retired in 2018

after nearly 40 years as a rare species biologist at the Rhode Island

Department of Environmental Management. Raymond Hartenstine served as a

volunteer field biologist.