Mueller did a poor job of putting the facts about Russia's election interference before the public

Howard Manly, The Conversation

In the long list of Donald Trump’s legal woes, the Mueller report – which was released in redacted form on April 18, 2019 – appears all but forgotten.

But the nearly two-year investigation into alleged Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election dominated headlines – and revealed what has become Trump’s trademark denial of any wrongdoing. For Trump, the Russia investigation was the first “ridiculous hoax” and “witch hunt.”

Mueller didn’t help matters. “While this report does not conclude that the president committed a crime, it also does not exonerate him,” the special counsel stated.

With such equivocal language, it’s easy to see how Democrats and Republicans – and the American public – responded to the report in completely different ways. While progressive Democrats wanted Trump to be impeached, some GOP leaders called for an investigation into the origins of the investigation itself.

Over the past five years, the Conversation U.S. has published the work of several scholars who followed the Mueller investigation and what it revealed about Trump. Here, we spotlight four examples of these scholars’ work.

1. Obstruction of justice

As a law professor and one-time elected official, David Orentlicher pointed out that Trump did many things that influenced federal investigations into him and his aides. They include firing FBI Director James Comey, publicly attacking the special counsel’s work and pressuring then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions not to recuse himself from overseeing Mueller’s investigation.

Some accused Trump of obstructing justice with these actions. But Orentlicher wrote that obstruction of justice is “a complicated matter.”

According to federal law, obstruction occurs when a person tries to impede or influence a trial, investigation or other official proceeding with threats or corrupt intent. The law requires a “corrupt” intention to obstruct justice as well.

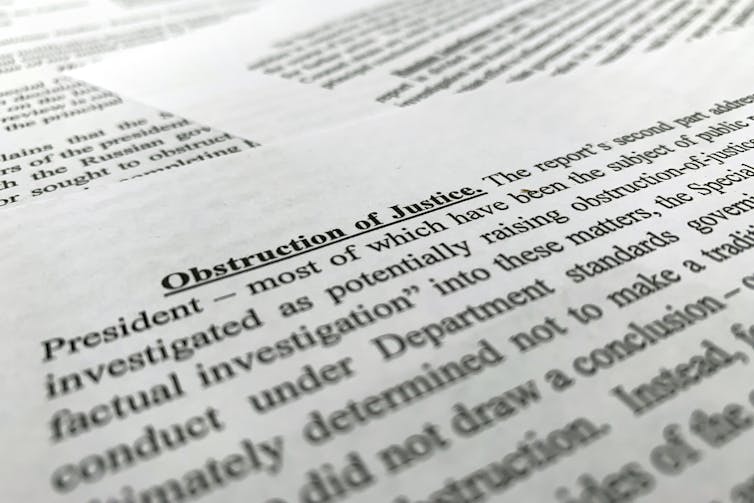

|

| William Barr’s letter to Congress summarizing the findings of Mueller’s report. AP Photo/Jon Elswick |

But in a March 24, 2019, letter to Congress summarizing Mueller’s findings, then-Attorney General William Barr said he saw insufficient evidence to prove that Trump had obstructed justice.

So it was up to Congress to further a case against Trump on obstruction charges, but then-Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi declined, arguing that it would be too divisive for the nation and Trump “just wasn’t worth it.”

2. Why didn’t the full report become public?

Charles Tiefer is a professor of law at the University of Baltimore and expected that Trump and Barr would do “everything in their power to keep secret the full report and, equally important, the materials underlying the report.”

|

| Attorney General William Barr was handpicked by Donald Trump to be in office when the Mueller report came in. AP Photo/Alex Brandon/Jose Luis Magana |

Trump and Barr also claimed executive privilege to further prevent the release of the report. Though it cannot be used to shield evidence of a crime, Tiefer explained, “that’s where Barr’s exoneration of Trump really helped the White House.”

3. Alternative facts

Political scientists David C. Barker and Morgan Marietta asked an important question: After nearly two years of waiting, why didn’t the report help the nation achieve a consensus over what happened in the 2016 presidential election?

In their book, “One nation, Two Realities,” they found that voters see the world in ways that reinforce their values and identities, irrespective of whether they have ever watched Fox News or MSNBC.

“The conflicting factual assertions that have emerged since the report’s release highlight just how easy it is for citizens to believe what they want, regardless of what Robert Mueller, William Barr or anyone else has to say about it,” they wrote.

Perhaps the most disappointing finding, they argued, is that there are no known fixes to this problem. They found that fact-checking has little impact on changing individual beliefs, and more education only sharpens the divisions.

And with that, they wrote, “the U.S. continues to inch ever closer to a public square in which consensus perceptions are unavailable and facts are irrelevant.”

4. Trump’s demand for loyalty

Political science professor Yu Ouyang studies loyalty and politics at Purdue University Northwest. He explained that it’s normal for presidents to prefer loyalists.

What sets Trump apart, Ouyang wrote, is his “exceptional emphasis on loyalty.”

Trump expects personal loyalty from his staff – especially from his attorney general.

When his first attorney general, Sessions, recused himself from overseeing the FBI’s probe into Russian meddling, Trump considered it an act of betrayal and fired him in November 2017. Session’s removal enabled Trump to hire Barr.

“Trump values loyalty over other critical qualities like competence and honesty. … And he appoints his staff accordingly,” Ouyang wrote.![]()

Howard Manly, Race + Equity Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.