INTERVIEW: Q & A with professor and author Mike Stanton

By G. Wayne Miller in

Ocean State Stories

Mike, let’s start with today. You live in Rhode Island

and are a journalism professor at the University of Connecticut. Tell

us about your responsibilities and the courses you teach.

Shana Novak

Having lived in Rhode Island for three decades, I didn’t

want to move when UConn hired me in 2013. I grew up in Connecticut, but love

Providence. So now I keep one foot in each state, which is interesting when

UConn plays Providence College in basketball – I have season tickets to the

Huskies and the Friars, who I used to cover for the ProJo!

I teach a range of courses, from our introductory Press in America and Newswriting I classes to more advanced courses like Investigative Reporting, Sports Journalism and Feature Writing.

My

investigative class last year published a project about housing evictions and

the affordable housing crisis in southeastern Connecticut in The Day of New

London. It won a national award for investigative reporting in the Hearst

student journalism competition. It’s a great example of the hands-on learning

that we stress.

What attracts your students to journalism?

Two things – storytelling and making a difference.

Since prehistoric cave paintings, humans have told

stories and that appetite continues, even as the platforms change. Students are

very excited to tell stories – through words, pictures, video, podcasts, etc. I

tell them that newspapers may be dying, but not the public’s hunger for stories

– and that they’re going to help invent the future.

Secondly, students are passionate about making a difference. Since the rise of disinformation and our fractured politics, we’ve seen an increase in students – even non-majors – who take Press in America because of a heightened awareness of the importance of a free press in a democratic society.

Some have changed their major to journalism or added it as

a second major. They want to do stories that hold the powerful accountable –

that afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted.

Give us an overview of where they hope to work – legacy newspapers, broadcast, online or somewhere else.

There’s a range. But they are finding jobs. Some work in legacy media, others for websites, or in broadcasting. Given our strong sports teams at UConn, and the proximity of ESPN in Bristol, Conn. (I co-teach Sports Journalism with ESPN feature producer Steve Buckheit), we have a lot of students who want to cover sports. Some work at ESPN; others have gone on to work as reporters and producers for Major League Baseball, including Molly Burkhardt, the daughter of two great journalists I worked with at the ProJo – the late Mimi and Andy Burkhardt.

Others get jobs on the social media side of

media companies, or doing social media for sports teams, etc. Data is another

field. One former student is at the New York Times, mining huge amounts of data

for investigative stories and graphics. Another worked for Tim White at WPRI as

an investigative producer. Another recent alum, Taylor Begley, is the sports

director at WPRI.

What’s the best bit of advice you’ve ever given to your

students?.

Get hands-on experience from Day One. The classroom is important, but it’s only part of the equation. Sign up right away to work for campus media and develop as many multi-platform media skills as you can to make yourself more versatile.

Dive immediately into journalism classes, so you can get to the more advanced courses faster and parlay your experience into internships that can lead to a job when you graduate. Too many college students focus in their first two years on knocking off their general-education requirements and don’t get into the advanced journalism courses until they’re juniors or seniors.

In the classroom,

we try to be as hands-on as possible, having students write news stories, cover

campus beats, attend sporting events, produce broadcasts and podcasts, etc.

Now, a bit of throwback. Years ago, we worked together

at The

Providence Journal – many fine memories! – where your specialty

was investigative journalism. What was the appeal – and importance – of that?

Rhode Island was a theme park for journalists – you had larger-than-life figures like Raymond Patriarca and Buddy Cianci and an assortment of characters and scoundrels. Providence was a target-rich environment.

I can’t think of a better place to learn the craft than at The Providence Journal in its heyday. At the ProJo, we had a proud tradition of not only investigative reporting but also storytelling and longform narrative journalism.

We had a story-of-the month contest in the newsroom that promoted

the craft of writing, and later some of those stories – and the accompanying

How I Wrote the Story – were published in book form.

I loved holding public officials accountable and the impact that our stories had. I worked with friends and colleagues like Tracy Breton and the late Bill Malinowski and who showed me the importance of shoe-leather journalism – knocking on doors and developing sources.

We had

editors like Joel Rawson and Tom Heslin who encouraged us to think big and take

risks. When a statewide banking crisis hit in early 1991, they took me out of

the Sports department for what was supposed to be a temporary assignment to help

cover it, and I never looked back.

And investigative journalism continues to play a vital

role in a democracy, correct?

Absolutely. Studies have found that communities that are

news deserts – with no reporters keeping track of what’s happening in town hall

or at the State House – have higher rates of corruption and lower levels of

voter participation.

You were on the team that won the

1994 Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting. For those who may

not know, tells us about what you investigated and the findings.

When I was covering the banking crisis, I developed a State House source who had inside information about a patronage empire that former House Speaker Matthew Smith had built at the state courts, where he had landed a cushy job as state court administrator.

Later, other ProJo reporters got wind of the fact that Smith had hired the n-er-do-well son of a political figure, who then stole money from a court fund. When Smith found out, he and his confederates covered it up.

We wrote stories about that, then moved on to

report on the patronage empire of Smith and Rhode Island Supreme Court Chief

Justice Thomas Fay, who had been Smith’s State House ally before his

appointment to the bench. That led to criminal investigations and their

resignations.

You are also an author. You first book was the

best-selling “The Prince of Providence.” For those who

may not have read it, give us an overview.

After we won the Pulitzer, several reporters on the investigative team moved on to bigger jobs – Dan Barry and John Sullivan to The New York Times, Ira Chinoy to The Washington Post, Dean Starkman to The Wall Street Journal.

I got a 1-year Knight Fellowship at Stanford, returned to take over the ProJo’s I-team, but was later offered a job at The Wall Street Journal. I accepted the job on a Friday, didn’t feel good about it over the weekend, then turned it down on Monday.

One reason I changed my mind: there were

rumblings of a federal corruption probe of Providence City Hall, and I had this

idea about writing a book about the case and Buddy Cianci. I knew if I left

that I would never write that book.

Buddy was a colorful character who had gained a nationwide following and who embodied the best and worst of American politics – All The King’s Men meets Goodfellas.

I called Jon Karp, a rising star at Random House who had gone to Brown and then worked briefly as a reporter at the ProJo. His immediate reaction: “I’ve been WAITING for someone to write a book about Buddy.” He connected me to his former Brown classmate, Andrew Blauner, who became my literary agent.

I wrote a book proposal and sold it to Random House

in the months after the FBI raided City Hall and Operation Plunder Dome became

public. (Another publisher who bid on the book had published a landmark

biography of Huey Long, which I thought put Buddy in good company! He wanted me

to call my book Rogue, but I liked the alliterative Prince of Providence, with

its bow to Machiavelli.)

I initially intended The Prince of Providence to chronicle the case – with the question of whether Buddy would survive serving as the narrative thread. But as I dug into the rich history, Plunder Dome became just the second half of the book.

The first half deals with Buddy’s rise and his first downfall – his early career as a Mafia prosecutor, his upset election in 1974 as Providence’s first Italian American mayor (and the anti-corruption candidate!), his first reign as major and downfall amidst corruption and the assault of his estranged wife’s suspected boyfriend with a fireplace log and lit cigarette.

Remarkably, of course, Buddy made a triumphant comeback six years later to preside over the Providence Renaissance (the moving of the rivers, Waterfire, etc.) until he was finally brought down by Operation Plunder Dome. The City of Providence and its rich history – Roger Williams, the Industrial Revolution, immigration, the Mafia, machine politics – is also a major character.

The book became a surprise New York Times bestseller and

endures to this day as a classic on American and urban politics. People give it

to people who move to Providence as a way of learning about their new home. The

Prince of Providence was adapted into a hugely successfully play at Trinity Rep

in 2019 (the theater’s biggest hit ever outside its annual Christmas Carol). It

still awaits a movie adaption that has stalled several times, despite interest

from actors ranging from Russell Crowe to Oliver Platt.

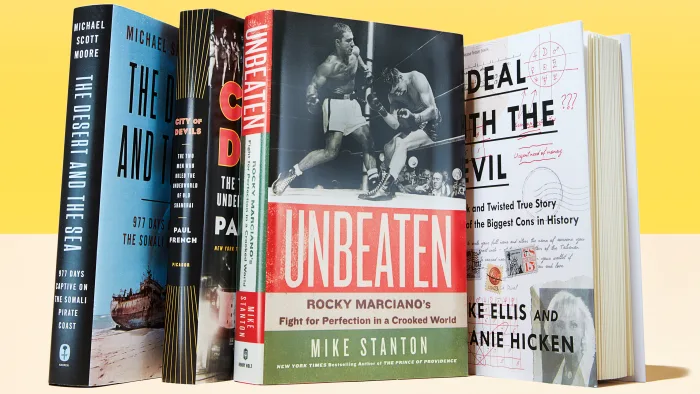

And tell us about your 2019 title, “Unbeaten: Rocky Marciano’s Fight for Perfection in a

Crooked World.”

Rocky Marciano, from Brockton, Mass., is history’s only unbeaten heavyweight boxing champion. I knew about him, but in researching The Prince of Providence, I learned that Buddy Cianci as a boy would go to the old Rhode Island Auditorium to watch Rocky fight in the late 1940s.

Turns out Rocky fought 29 times in Providence enroute to the title. Then, after my father died, I was going through his papers and found an autographed Rocky poster – Dad had gone to Bryant in the early 1950s, when the campus was in Providence, and met Rocky.

I was fascinated to re-create this Runyonesque, Guys & Dolls world of mid-20th Century America, when boxing was as popular as the NFL is today, with celebrity studded, sold-out fights in Madison Square Garden and Yankee Stadium. Boxing also embodied the immigrant struggle. And the sport was controlled by the Mafia, which was notorious for fixing fights and in fact tried to, and may have, fixed a few of Rocky’s fights.

I was fascinated at how Rocky navigated the corrupt and brutal world of boxing to achieve perfection, then walked away in his prime – which few athletes do – with that 49-0 record. Later in life, in retirement, he bonded with his seemingly polar opposite, Muhammad Ali. I interviewed Ali’s wife at the time, who told me how Ali and Marciano discussed going to American’s inner cities together to preach racial harmony.

This was amidst the riots of the late 1960s – and weeks before Marciano’s death in a plane crash, so it never happened. I wrote Unbeaten as a social history that appeals to people who aren’t hard-core boxing fans, and it won praise as a best book of the year from The Boston Globe, Wall Street Journal and Times of London.

It’s the only

definitive biography of Rocky, and I uncovered some previously unknown stuff –

like his Army court-martial in England during World War II. I remember going to

the National Archives and that aha moment when I discovered a complete

transcript of the court martial, old medical records and even Rocky’s mugshot,

which appears in the book.

In addition to everything else, you were a Boston Globe

Spotlight fellow. What did that entail?

That was a cool experience. The Hollywood filmmakers of the Academy Award-winning film Spotlight funded a fellowship at the Globe for investigative reporting. The Globe’s Spotlight Team is the gold standard, especially for a kid who grew up in New England.

Years ago, I’d been a finalist for a job at Spotlight but didn’t get hired. I applied for the fellowship with a proposal to write about the natural gas industry in New England. I focused on the controversial construction of a natural-gas compressor on the waterfront south of Boston, in Weymouth.

It was the lynchpin in a major gas line from

Pennsylvania that feeds New England. I used that story to show how state and federal

agencies that approve big energy projects are often captured by industry, with

local residents who fight the projects for health, safety and climate-change

reasons standing little chance against these Goliaths.

The decline of legacy newspapers has left many parts of

the country news deserts – and gutted many once-leading publications. What

threat does that pose to communities and democracy in general?

It creates a vacuum that is filled by disinformation and

puts people in silos, leaving them disconnected and unable to agree on basic

facts. Look at the recent Baltimore bridge disaster. Instead of focusing on

what happened, you have some people claiming on social media that the accident

was caused by diversity and equity initiatives.

We talk about this a lot in my classes at UConn. As I mentioned earlier, studies show that in the absence of local news coverage, voter participation declines and corruption rises.

This is not a partisan thing – this is about simply telling people what’s happening on their town council, with their city budget, at their police department, in their schools.

I had a student at UConn from Long Island – the district where George Santos

was elected to Congress– and she spoke in class about how, during his campaign,

few reporters paid attention to the gaping holes in Santos’s resume. There was

one small local paper that wrote some things, she said, but few people paid

attention. If reporters had been watching, Santos probably wouldn’t have been

elected.

Talk about role being played by the many non-profit

online news outlets that have emerged in recent years. You are vice chair of

the board of ecoRI News, a publication partner of

Ocean State Stories, which is also a 501(c)(3) nonprofit.

This is an exciting development in journalism – the efforts of various non-profits to fill the vacuum left by the decline of legacy media. We’re in the midst of an exciting expansion at ecoRI News.

We have a Report for America reporter, Colleen Cronin. We have a new editor, Bonnie Phillips – a Rhode Island native who spent years as a top editor at the Hartford Courant, where she shared a Pulitzer for coverage of Sandy Hook. Frank Carini, our co-founder and one of our writers/columnists, was recently recognized for his environmental writing by being Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse’s guest at the State of the Union address.

Other newsrooms, like Rhode Island Current and Ocean State Stories, are providing new forums. Rhode Island’s public radio and television stations are merging. I did really some fun stories about Narragansett Bay and seafood last year for ecoRI News as part of a new partnership with Rhode Island Public Television that also aired as a story on RI PBS Weekly.

It was great working

with them – they taught this old dog some new tricks! The Rhode Island

Foundation is looking at ways to support local news as part of a new national

initiative called Press Forward, which has the backing of such groups as the

MacArthur Foundation and the Knight Foundation. I’m excited to see where that

goes.

What’s next for Mike Stanton?

In the short term, I’m looking forward to hosting author

talks later this month with two writers with Rhode Island ties whom I admire.

On April 20, at Barrington Books, I’ll be talking

with best-selling author Don Winslow about the final book in his Rhode

Island/Danny Ryan trilogy, City in Ruins, about a Providence mob war based on

the Iliad.

And on April 25, at Books on the Square, I’ll be

talking to former Providence Phoenix editor and local freelance author Phil Eil

about his new book, Prescription for Pain, which chronicles a remarkable

true-crime case of a major pill-mill doctor in the opioid epidemic.

As for my own writing, it’s funny how one book leads to another. Writing about Buddy Cianci and Rocky Marciano, one name that kept popping up was Raymond Patriarca, the longtime former New England Mafia boss. I’m working on a biography of him.

There’s no timeline yet. I’m going through

the voluminous files I’ve gathered over the years, including his 7,000-page FBI

file, to organize the story and develop a book proposal. There’s some wild and

crazy stuff there! I’m excited to tell the story of a man whose life

encompasses the rise and fall of the American Mafia, from the bootlegging days

of Prohibition to the rise of the Las Vegas casinos.

I call it my Rhode Island Trilogy!