Can the Biden Administration really curb them?

By DEAN

BAKER

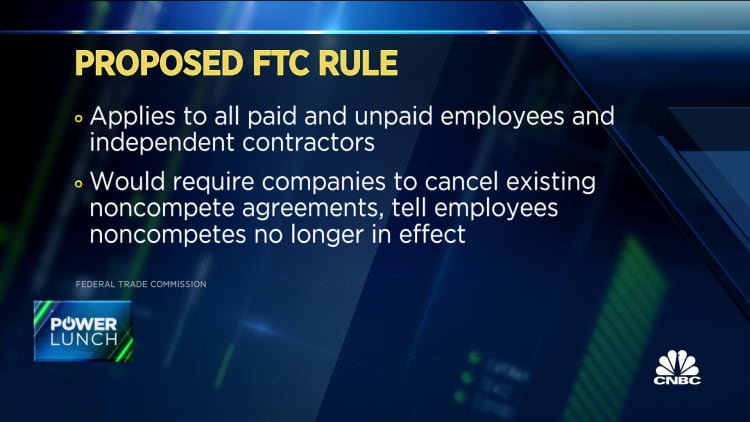

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) on April 23 voted to finalize a ban on most noncompeteclauses.

Since announcing its plan to adopt rules on noncompete clauses last year the FTC has received more than 26,000 comments.

Noncompete clauses were originally only included in contracts for highly paid workers. For example, lawyers at a large firm might be limited in their ability to leave and take their clients with them. But noncompete contracts have become much more widespread in recent decades.

They

often prevent lower-paid workers, such as barbers or beauticians, from starting

their own business or working for a competitor. In one famous case, a

fast-food chain actually limited the ability of their

employees to get jobs elsewhere.

The effect of noncompete clauses is to reduce the wages

of workers affected by them.

The direct impact on workers subject to clauses could

be as much as 15 percent, and the impact on all

workers’ pay could be over 8.0 percent. In short, they are a big deal in

determining wages and the distribution of income.

Cost Per Worker

America’s 161.4 million job holders would earn $300

billion more were noncompete clauses banned. That works out to about

$1,800 annually per worker.

The question the FTC considered is whether all or

only some noncompete clauses should be unenforceable.

Anyone who thinks that making them unenforceable would be

a case of the government interfering in the market needs to think further. The

government always decides what sort of

contracts it will enforce.

To take one from history, in England it used to be common

to have encumbrances attached to property that was inherited or sold. These

often gave relatives of the original owners claims against a property, such as

a share of the harvest of a farm. Most such encumbrances are no longer

enforceable.

A more recent type of unenforceable encumbrance was the

provisions in many real estate deeds that a property could never be sold to a

Black, Jewish, Asian, or indigenous person. The government will not enforce

such provisions.

Work for Less Laws

Taking an example in the labor arena, 28 states have “right-to-work” laws. These are misnamed because they actually have little to do with anyone’s right to work. What they actually do is ban contracts that require all employees in a workplace represented by a union to pay a representation fee to the union.

Such a contract would be unenforceable in one

of these states because in 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court held that they violated the equal

protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

Another example of the government superseding contracts

is bankruptcy laws. Under bankruptcy law, the government tells creditors that

they can’t collect on legal obligations regardless of the contractual

provisions they may have agreed to.

This issue comes up not only with explicit loans between a borrower and lender, but can also arise with unintended creditors, such as a supplier who has delivered goods, a landlord waiting for rent, or a worker waiting for wages.

Donald Trump took advantage of this loan forgiveness program

four times (and his casino company successors two more times), something

perhaps worth considering in the context of President Biden’s student loan

forgiveness program.

The point here is that contracts don’t enforce

themselves. They rely on the government to use its police power to make the

parties follow through on obligations. There are all sorts of contracts that

the government will refuse to enforce or will not enforce in the ways written.

Contracts that explicitly discriminate based on race or sex are the most

obvious examples.

The FTC assessed whether noncompete clauses are the

sort of agreement the government should be enforcing. We know the impact of

enforcing these clauses is to lower wages. The issue before the FTC is whether

or not it is good to lower wages and limit workers’ employment opportunities.

There is no “free market” issue in this story.

Dean Baker co-founded

the Center for Economic and Policy Research in 1999. His areas of research

include housing and macroeconomics, intellectual property, Social Security,

Medicare and European labor markets. He is the author of several books,

including "Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy

Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer."