June 1 could see the start of the worst hurricane season in US history

Jhordanne Jones, Purdue University

|

| The U.S. is in for another busy hurricane season. Here are hurricanes Irma, Jose and Katia in 2017. NOAA |

If the National Hurricane Center’s early forecast, released May 23, is right, the North Atlantic could see 17 to 25 named storms, eight to 13 hurricanes, and four to seven major hurricanes by the end of November. That’s the highest number of named storms NOAA has ever forecast for a hurricane season.

Other forecasts for the season have been just as intense. Colorado State University’s early outlook, released in April, predicted an average of 23 named storms, 11 hurricanes and five major hurricanes. The European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts anticipates 21 named storms.

Colorado State also forecasts a whopping 210 accumulated cyclone energy units for 2024, and NOAA forecasts the second-highest ACE on record. Accumulated cyclone energy is a score for how active a given season is by combining intensity and duration of all storms occurring within a given season. Anything over 103 is considered above normal.

These outlooks place the 2024 season in league with 2020, when so many tropical cyclones formed in the Atlantic that they exhausted the usual list of storm names: A record 30 named storms, 13 hurricanes and six major hurricanes formed that year, combining for 245 accumulated cyclone energy units.

So, what makes for a highly active Atlantic hurricane season?

I am a climate scientist who has worked on seasonal hurricane outlooks and examined how climate change affects our ability to predict hurricanes. Forecasters and climatologists look for two main clues when assessing the risks from upcoming Atlantic hurricane seasons: a warm tropical Atlantic Ocean and a cool tropical eastern Pacific Ocean.

Warm Atlantic water can fuel hurricanes

During the summer, the Atlantic Ocean warms up, resulting in generally favorable conditions for hurricanes to form.

Warm ocean surface water – about 79 degrees Fahrenheit (26 degrees Celsius) and above – provides increasing heat energy, or latent heat, that is released through evaporation. That latent heat triggers an upward motion, helping form clusters of storm clouds and the rotating circulation that can bring these storm together to form rainbands around a vortex.

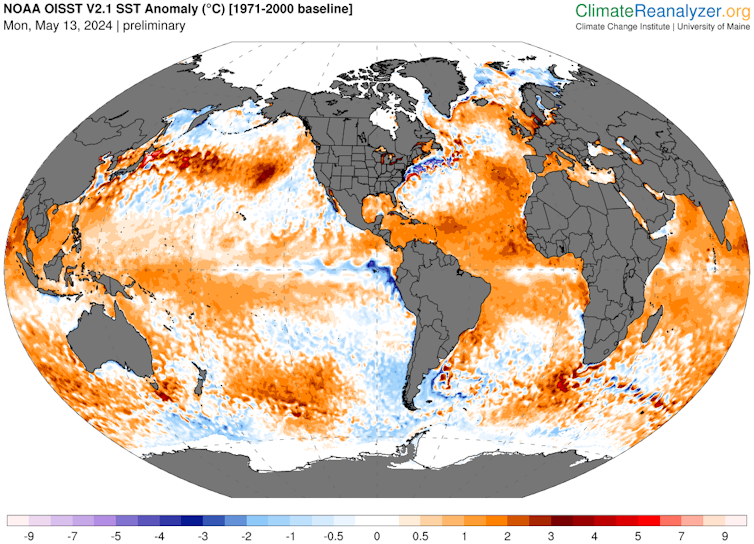

Ocean heat in 2024 is a big reason why forecasters are warning of a busy hurricane season.

The North Atlantic sea surface temperature has been shattering heat records for most of the past year, so temperatures are starting out high already and are expected to remain high during the summer. Globally, ocean temperatures have been rising as the planet warms.

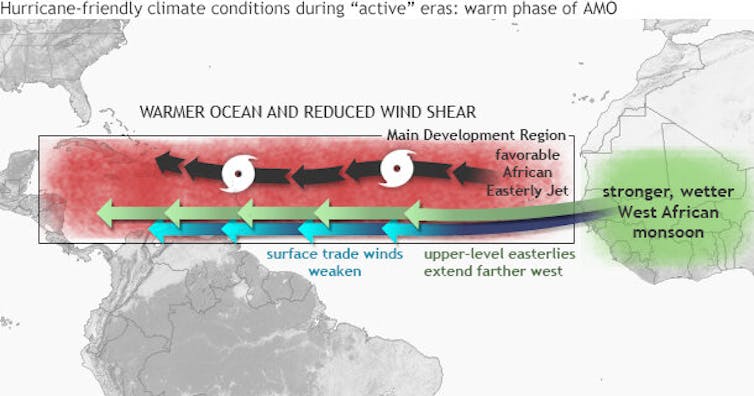

A long-term temperature pattern known as the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation, or AMO, also comes into play. The summer Atlantic ocean surface can be warmer or cooler than usual for several seasons in a row, sometimes lasing decades.

Warm phases of the AMO mean more energy for hurricanes, while cold phases help suppress hurricane activity by increasing trade wind strength and vertical wind shear. The Atlantic Ocean has been in a warm phase AMO since 1995, which has coincided with an era of highly active Atlantic hurricane seasons.

How the Pacific can interfere with Atlantic storms

It might seem odd to look to the Pacific for clues about Atlantic hurricanes, but Pacific Ocean temperatures also play an important role in the winds that can affect hurricanes.

Like the Atlantic, water temperatures in the eastern Pacific oscillate between warm and cold phases, but on shorter time spans. Scientists call this the El Niño Southern Oscillation, or ENSO. The warm phases are known as El Niño; cold phases are called La Niña.

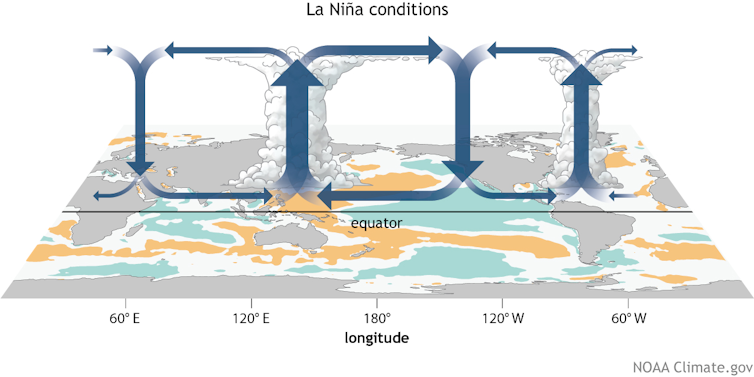

La Niña promotes the upward motion of air over the Atlantic, which fuels deeper rain clouds and more intense rainfall.

La Niña’s effects also weaken the trade winds, reducing vertical wind shear. Vertical wind shear, a difference in wind strength and direction between the upper atmosphere and the atmosphere near Earth’s surface, makes it harder for hurricanes to form and can pull apart a storm’s vortex.

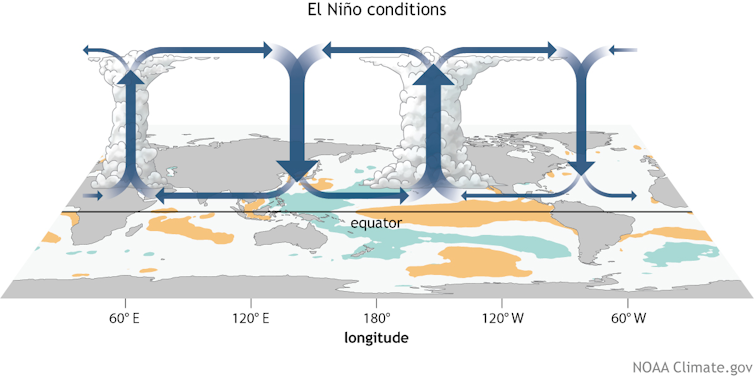

In contrast, El Niño promotes stronger trade winds, increasing wind shear. It also centers the upward motion and rainfall in the Pacific, triggering a downward motion that promotes fair weather over the Atlantic.

El Niño was strong during the winter of 2023-24, but it was expected to dissipate by June, meaning less wind shear to keep hurricanes in check. La Niña conditions are likely by late summer.

Where ENSO is in its transition may determine how early in the season tropical storms form – and how late. A quick transition to La Niña may indicate an early start to the season as well as a longer season, as La Niña – along with a warm Atlantic – maintains a hurricane-friendly environment earlier and longer within the year.

This ocean tag team controls hurricane activity

The Atlantic and eastern Pacific ocean temperatures together control Atlantic hurricane activity. This is like bouncing in a bounce house or on a trampoline. You get a good bounce when you’re jumping on your own but reach far greater heights when you have one or two more people jumping with you.

When the eastern Pacific is in its cold phase (La Niña) and the Atlantic waters are warm, Atlantic hurricane activity tends to be more frequent, with a higher likelihood of more intense and longer-lived storms.

The record 2020 hurricane season had the influence of both La Niña and high Atlantic ocean temperatures, and that’s what forecasters expect to see in 2024.

It is also important to remember that storms can also intensify under moderately unfavorable environments as long as there is a warm ocean to fuel them. For example, the storm that eventually became Hurricane Dorian in 2019 was surrounded by dry air as it headed into the Caribbean, but it rapidly intensified into an extremely destructive Category 5 hurricane over the Bahamas.

This article has been updated with NOAA officials describing the forecast as the highest number of storms it has ever forecast.![]()

Jhordanne Jones, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Climate and Weather Extremes, Purdue University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.