American women are doing more than just protest

Linda J. Nicholson, Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

As someone who over the past 50 years has thought about and written many books and articles on U.S. feminism, I should have been less surprised by the strong electoral backlash to the Supreme Court’s 2022 Dobbs V. Jackson Women’s Health Organization ruling, a judgment that overturned the 1973 Roe V. Wade decree and thus 50 years of national abortion rights.

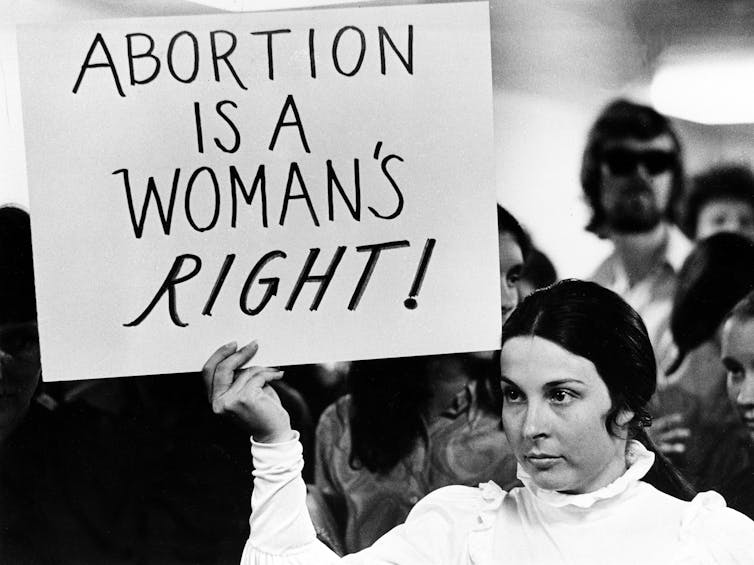

A young woman holds a sign demanding a woman’s right

to an abortion at a protest following the closing of a

Madison, Wis., abortion clinic on April 20, 1971.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

True, I expected massive street demonstrations and marches after Dobbs was announced, the kind of political actions that abortion-rights supporters used in the years before Roe was enacted – and in the years since, as abortion rights continued to be challenged.

But surprising to me, and to many others, was the nature of the backlash. People were taking their outrage not only to the streets but to the ballot box as well.

In August 2022, for example, 60% of voters in Kansas easily defeated a proposed state constitutional amendment that would have taken away abortion rights in Kansas.

Abortion rights also motivated many existing and new Democratic voters to turn out during the 2022 midterm elections, causing Republicans to fare worse than expected.

Similar favorable outcomes for Democrats also occurred in special elections in places such as Virginia and Ohio in 2023.

And now, heading into the presidential election in November, abortion rights continues to command a central spotlight in American politics.

Why have abortion rights so recently come to occupy such a center stage in our state and national elections? I believe that over the past few decades, there have been major shifts in how women live, view themselves and are viewed by others.

As long as Roe was in place, these shifts could coexist with the abortion rights Roe provided. When Roe was overturned, the clash between these newer versions of womanhood and the elimination of such rights led to major outrage at the ballot box.

Feminism in the ’60s

The story begins in the 1960s, when feminism became a loud presence on the national political stage. Women founded the National Organization for Women, or NOW, in 1966.

NOW initially came together over anger that the national Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, tasked with equalizing opportunity in the labor force, was not taking a stand against sex-segregated want ads. A central focus of NOW became ensuring that women should have the same options as men in the paid labor force.

Later in the 1960s, younger women formed a separate movement, calling it “women’s liberation,” and argued for greater equality between men and women in private life – not just the workplace – and for women to have greater control over their bodies.

This movement created the popular slogan “the personal is political.” In 1970, a women’s collective in Boston printed the first edition of “Our Bodies, Our Selves,” a book focused on giving women greater knowledge of and control over their bodies.

Motherhood, marriage and abortion in the ’60s

Neither of these movements accepted the popular view that unexpected pregnancies ought to be carried to term, a view based on the belief that women’s primary role in society was that of wife and mother.

Alongside this social norm of women’s proper roles came the idea that if a married woman unexpectedly got pregnant, the pregnancy should be embraced. Married women who rejected such a pregnancy were viewed as selfish.

Unmarried women, meanwhile, were shamed, sometimes sent away from their homes, and pressured to give up the baby for adoption.

In response, feminists, both in NOW and within the women’s liberation movement, demanded increased access to birth control and abortion. A first-of-its-kind abortion-rights group, The National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws, was formed in the late ’60s. In Chicago, in 1969, feminists also organized an underground abortion access network called Jane.

From the 1960s to today

While NOW’s creation was noteworthy, the professional women who came together to create the group formed only a small part of the U.S. population. In the late 1960s, women who had a college degree were only 8.2% of the population, compared with 38.3% in 2021.

And those who were active in early women’s liberation groups were mostly young and veterans of other protest movements of the 1960s, all of which set them apart from many Americans.

But if, initially, these groups were not large in number, many of the ideas they called for seeped into American institutions or were instrumental in creating new forms of awareness in subsequent decades.

Women, for example, have continued to enter the workforce in larger numbers since the 1960s. In 1968, approximately 45% of women over the age of 16 had paying jobs.

Demonstrators rally for abortion rights outside the

U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., on Nov. 20, 1971.

Associated Press

In 2021, that rate was about 57%. And this growth included not just poor women, who have almost always had to contribute to household finances, or single women working before marriage and motherhood, but increasingly middle-class married women.

Women have come to think of paid work differently, too, since the 1960s. Paid work for women has steadily become not just a means to increase family income but also a source of self-identity.

While this has been more true for higher-income women than for lower-income women, lower-income women have also, to a greater extent, come to see their work lives as an important part of who they are.

Women’s control over their bodies

Since the 1960s, women have also increasingly come to believe that they should control their own bodies and their own sexuality.

In the late 1970s, feminists organized “Take Back the Night” marches, which asserted women’s right to freedom from assault by men at night. In the late 1970s, feminists brought the issue of domestic violence to public attention, creating shelters for the victims of domestic violence and pressuring politicians to put in place laws that would meet the needs of victims.

During the 1980s, rape became more widely understood as something that could happen within a marriage or between people who were dating or just acquaintances.

It wasn’t until 2017 that the #MeToo movement developed on social media. Shortly after, women – some of them well-known public figures – posted this hashtag, and powerful men, such as Harvey Weinstein and Bill Cosby, were accused of sexual harassment and abuse. In many cases, these men lost their jobs and some went to prison for their actions.

This stands in contrast to 1991, when Anita Hill accused Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas of making inappropriate sexual comments to her. She faced an uphill battle in getting her charges taken seriously, and people undermined the credibility of her charges with attacks on her character.

American womanhood is not what it used to be. A larger portion of women see themselves and are seen by others differently than was the case in the early 1970s. And that means that laws that give power to politicians to control women’s bodies are even more out of sync with a large swath of the population than they were at the time of the Roe ruling.

I, like many others, thought that the Dobbs decision would simply take us back to the pre-Roe period with massive demonstrations and marches, but not much more. It turns out that an unexpected number of women and their supporters had a different plan.![]()

Linda J. Nicholson, Susan E. and William P. Distinguished Professor of Women and Gender Studies and Professor of History Emerita, Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.