Another Trump term means institutionalized corruption

Sidney Shapiro, Wake Forest University and Joseph P. Tomain, University of Cincinnati

|

| By Bill Bramhall |

The United States has tried such a plan before.

As we write in our book “How Government Built America,” newly elected President Andrew Jackson, after he took office in 1828, fired about half the country’s civil servants and replaced them with loyal members of his political party.

The result was not only an utterly incompetent administration, but widespread corruption.

Swearing allegiance

Jackson’s actions that rewarded political loyalists and punished enemies were a dramatic departure from what the founders had envisioned by establishing an independent civil service whose members were literally pledged to uphold the country’s laws.

In passage of its very first law, on June 1, 1789, Congress required newly appointed federal officials to take the oath of office to uphold the laws of the country and faithfully carry out their duties.

Congress also passed conflict-of-interest legislation at that time to prevent employees from making decisions based on personal financial considerations.

While oaths may have less significance today, they were regarded as significant personal commitments in the 18th and 19th centuries. The U.S. Constitution, for example, contains an oath of office for the president, and it specifies that members of Congress and other federal officials “shall be bound by Oath or Affirmation to support this Constitution.”

When President George Washington – and the next five U.S. presidents – hired a new employee, reputations mattered. Each of the presidents looked at how an appointee’s neighbors regarded him and whether he had been elected to local office, an indication that the man – and they were all men – was competent and an honest employee.

That’s not what Jackson, the nation’s seventh president, and his system aimed to do; he wanted loyalists in government jobs.

The spoils system

While the first presidents were concerned with the competence and honesty of civil service employees, Jackson quickly set aside those concerns.

Instead of hiring those who wanted to work for the public interest and the good of the nation, Jackson employed members of his political party who pledged to march in lockstep with him and his policies. This became known as the “spoils system.”

Like Trump, Jackson also had a version of the “deep state” that he opposed. He claimed that the appointment process was aristocratic and blocked the appointment of the ordinary people he represented. He also insisted that experience and competence were unnecessary.

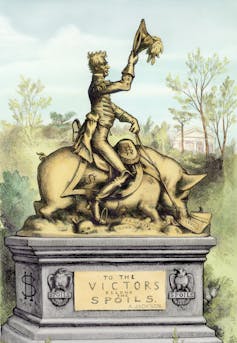

|

| A cartoon of President Andrew Jackson atop a pig depicts his spoils system, which rewarded party members with government jobs. Bettmann/GettyImages |

Jackson was quite wrong about some of his political appointments.

One of his worst was Samuel Swartwout, a longtime Army friend and political sycophant. Jackson named him to two consecutive terms as collector of customs at New York, where he served from 1829 through 1837.

Considered a plum assignment, the job at the time was the highest paid in federal government and involved collecting taxes and fees on imported goods that arrived in the nation’s busiest port.

But a congressional investigation showed that Swartwout had stolen a little more than US$1.2 million during his tenure, or about $40 million in today’s dollars.

Swartwout had fled to London, but he returned to the U.S. after he was assured that he would not face criminal charges.

Jackson also learned that his power to influence federal agencies with high-level appointments was limited. Such was the case with the U.S. Postal Service.

As a slaveholder, Jackson was disturbed by the mailing of antislavery flyers in 1835 by the American Anti-Slavery Society. Fearing the flyers would lead to a Black insurrection, Jackson instructed his postmaster general, Amos Kendall, an enslaver himself, to fix their problem by limiting the mailings and asking Congress to prohibit the U.S. Postal Service from mailing all abolitionist material.

Congress refused, citing freedom of speech and expansion of presidential authority as the main reasons.

Long after Jackson had left the White House, Congress, between 1864 and 1883, debated making “merit” a key condition of hiring new employees, but nothing happened until after a disgruntled office seeker assassinated President Chester Garfield.

Congress then passed the Pendleton Act in 1883, which established the merit appointment system still used today. It also put a virtual end to a system that allowed whichever party that won the White House to reward its supporters with tens of thousands of jobs.

A limited exception

Currently, most of the nearly 3 million federal employees are appointed using merit-based hiring that relies on competitive exams. They cannot be fired except for a limited set of reasons, such as poor performance or misconduct.

But the law exempts about 4,000 federal employees whose appointment requires the Senate’s advice and consent and who have been determined by the president to hold a “confidential, policy-determining, policy-making or policy-advocating character.”

The idea is to give a new president the capacity to influence his policymaking by hiring top-level federal officials.

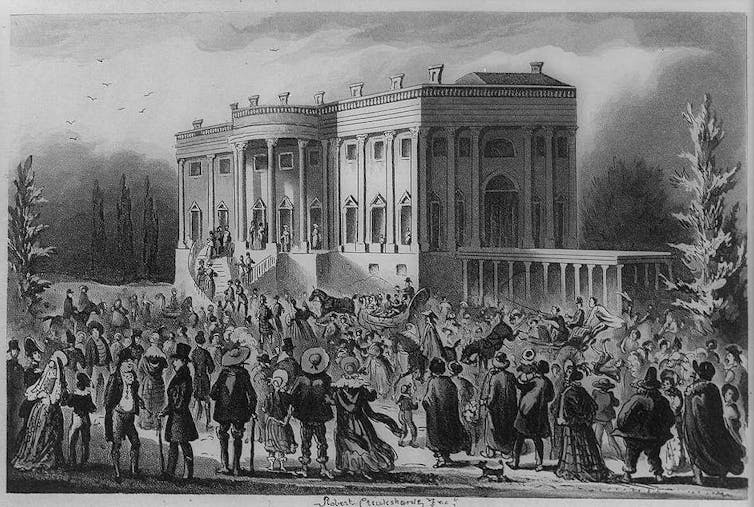

|

| People seeking government jobs crashed the White House on the day of Andrew Jackson’s inauguration. Library of Congress |

In short, he intends to reestablish the spoils system.

This is no idle threat.

Near the end of his administration, then-President Trump signed an executive order establishing a new job classification within the government’s career civil service called Schedule F for “employees in confidential, policy-determining, policy-making or policy-advocating positions.”

Under that designation, employees would lose virtually all of their civil service protections and could be fired without cause. It’s unclear how much effect Trump’s order had on the federal government because it was enacted two weeks before the 2020 election and was in effect for only a few months.

Shortly after taking office, President Joe Biden reversed Trump’s order.

A thankless task

In our view, if political loyalty replaces merit as the basis of key federal appointments, Americans can expect government to be less competent – as Andrew Jackson learned during his administration.

While this might not matter to those who regard government as unimportant to the country – or worse, the enemy of the country – our book “How Government Built America” tells a much different story about the thousands of federal employees who provide everything from health services to protection from natural disasters.

Not every civil servant is a great employee, nor is every employee of private industry.

But there is ample proof that government works because of the many people behind the scenes in Washington and across the country who serve the American people – and uphold their oaths of office.![]()

Sidney Shapiro, Professor of Law, Wake Forest University and Joseph P. Tomain, Professor of Law, University of Cincinnati

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.