Given its history, SHOULD it?

By Colleen Cronin / ecoRI News staff

|

| The nuclear reactor at URI's Bay Campus was built in 1960. For more than 50 years it has provided data to researchers and students. (RI.gov) |

As Rhode Island tries to reach its climate goals, the

discussions of solar panels and wind turbines are starting to include another

carbon-free energy source: nuclear power.

Anti-wind power advocates have

offered it as an alternative to ocean wind farms — which have come under fire

after a blade at a wind farm off Nantucket failed this summer — while power

brokers, including Microsoft founder Bill Gates and former Secretary of State John

Kerry, are suggesting it might be the most efficient way to get to

carbon neutral.

Fears around this type of energy, which does not produce carbon emissions but

has caused several deadly catastrophes, including one in Rhode Island 60

years ago, has prevented development of nuclear power plants over

the past several decades.

But improvements in technology and a push to decarbonize

could make nuclear more pervasive, though obstacles still remain before

large-scale nuclear power could come to Rhode Island.

Rhode Island already has one nuclear reactor, but like the

state itself, it’s small. It’s a research reactor on the University of Rhode

Island’s Bay Campus.

Built

in the 1960s, the reactor was originally

constructed to test different materials’ vulnerability to radiation, according

to Clinton Chichester, chair of the Rhode Island Atomic Energy

Commission, which oversees the reactor.

Today, the reactor is largely used for engineering and

medical research.

“The research reactor is so limited in size, it is very safe in terms of operations,” Chichester said. “The amount of radioactivity is orders of magnitude smaller than a power plant, and we don’t have water circulating from the bay through the reactor or anything like that.”

Federal officials inspect the reactor four times a year, and

according to recent U.S. Nuclear Regulatory

Commission Reports, it is in compliance with safety and security

regulations.

“I really have no concerns about safety about the small

research reactor because it’s so small,” Chichester said.

A nuclear power plant would be a completely different

situation, he said.

Although Chichester said he’s confident in the safety of

URI’s reactor and supports the important research that it helps facilitate,

when asked if he would be comfortable living next to a nuclear power plant, he

wasn’t sure.

“I’d have to think about it,” he said. A nuclear power plant

using current technology would need significant cooling resources, Chichester

thought out loud, and Rhode Island is such a densely populated state. A power

plant might have to be cited near the ocean.

“Who wants to disturb Narragansett Bay?” he asked. “I

wouldn’t go for that, for sure.”

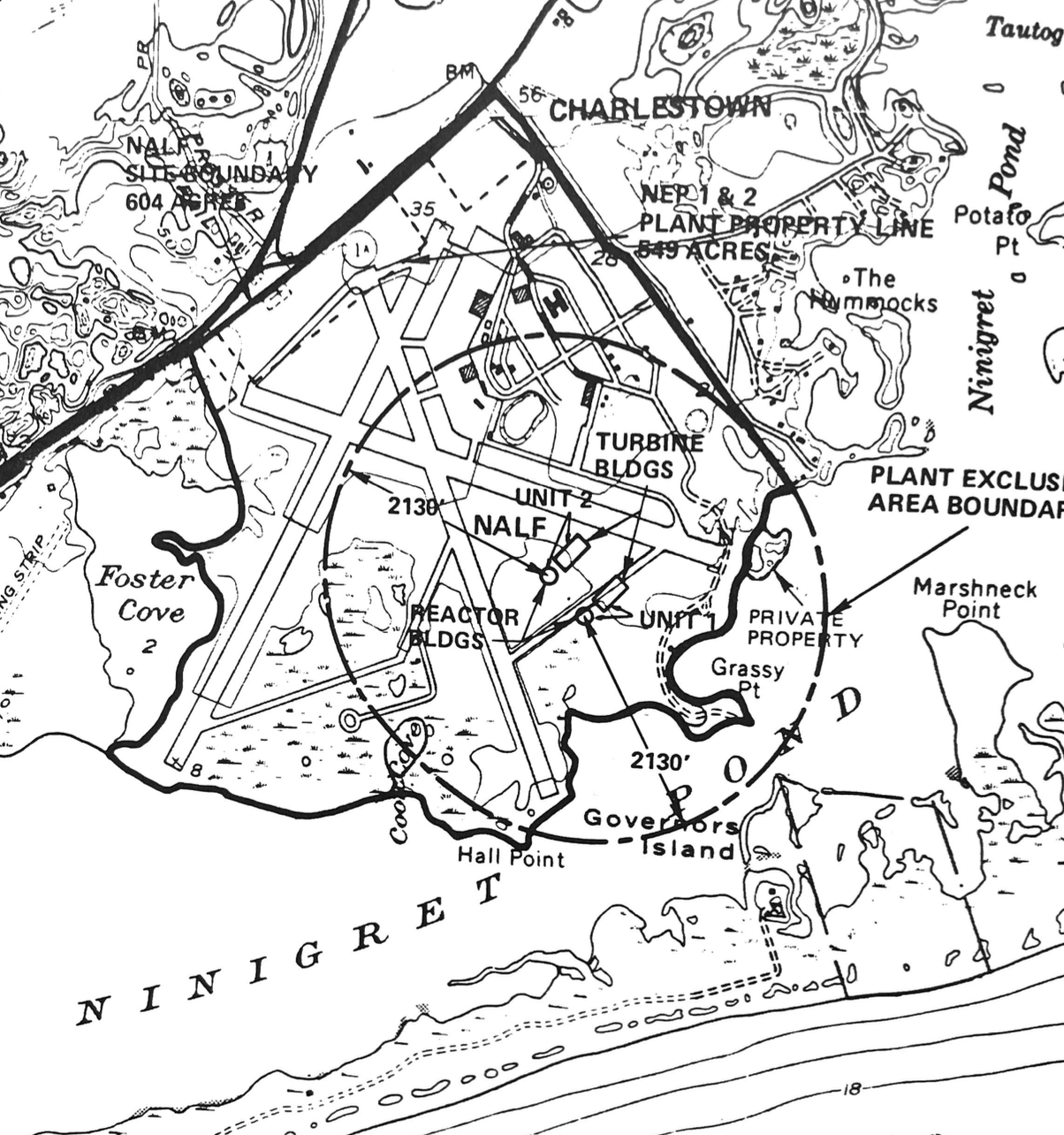

There have been attempts in the past to bring nuclear energy

to Rhode Island. In the 1970s, residents of Charlestown fought a proposed plant

that would have been constructed at what is now Ninigret Park.

|

| Residents and state officials fought the siting of a nuclear power plant in the 1970s at what is now green space in Charlestown. (Rhode Island Historical Society.) |

Donna Walsh, a former state representative and former

Charlestown Town Council member, recalled advocating against it at the time.

“I live very, very close to Ninigret Park, but I still would

have been against it” even if she didn’t live where she did, she said.

Instead of becoming a power plant, the park is now a green space and wildlife refuge.

“We’re very fortunate to have Ninigret Park,” Walsh said.

When the plant was proposed, the country was in the middle

of a gas crisis, so there was a lot of pressure to go nuclear, Walsh said. It

was before the Three Mile Island nuclear plant in Pennsylvania underwent a

partial meltdown in 1979, but Walsh said she was still greatly concerned about

the danger of an accident and the damage that could be caused by nuclear waste,

a byproduct of the nuclear energy process.

The waste in particular, and where it would go, was a big

worry for Walsh. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, most nuclear waste today

is kept at department sites and is regulated under federal laws. Scientific American reported

last year that these repositories are piling up, which could be a problem in

the future.

Less than a decade before Charlestown’s plant was proposed,

an accident at a Rhode Island facility that dealt with nuclear waste resulted

in one death.

Thinking about nuclear now, Walsh said, she isn’t sure how

she feels.

“It would be a help in [reversing the] climate change

process we’re in,” she said, “but I couldn’t say I support it. I’d be pretty

apprehensive, unless I had my questions answered.”

Walsh also said she wouldn’t like to live near a nuclear

power plant, and “if I don’t want to, I’m sure others don’t.”

“I know I can change my mind,” she added, “but I’m not ready

to change it yet.”

If a nuclear power plant were built in Rhode Island, it

would have to first be approved by the General Assembly.

Rep. Brian Kennedy, a Democrat representing District 38 in

Hopkinton and Westerly, has tried to pass legislation to remove this step, but

it hasn’t been successful.

Kennedy told ecoRI News that he was motivated to write the

bill after going to a national conference and learning about new nuclear

technology, and after becoming frustrated with the limitations of wind and

solar farms.

“My area of the state has been overrun by solar,” he said,

with forested places cut down for large solar farms taking up acres of space.

Typically, nuclear power plants in

the United States use nuclear fission (the splitting of an atom) to produce

heat. The heat boils water, creating steam, which powers turbines that generate

electricity. The process doesn’t create any carbon emissions, though it can

cause water pollution by

changing the water temperature, thus degrading it.

But new technology being pioneered by companies like Bill Gates’s TerraPower are

testing systems that use liquid sodium instead of water, which theoretically

reduces the amount of space the reactor needs to operate and makes it safer.

Kennedy also said nuclear power plants have the added

benefit of being able to run 24/7, something weather-dependent wind and solar

farms can’t do.

Removing the requirement to get the General Assembly

permission for every new nuclear project, Kennedy thought, might allow the

state to consider the prospect of nuclear power more seriously.

“We have to open the discussion,” Kennedy said.

“Probably I would not enjoy living next to any type of

electrical generating facility,” he admitted, when asked whether he would feel

comfortable living near a nuclear power plant. But because new plants may not

take up as much space in the future as other energy producers, “you hopefully

can keep a whole bunch of trees up” to block it from view.

Kennedy said he will reintroduce the bill, which was held

for further study in the last legislative session.

“It makes sense for us to take at least one obstacle away,”

he said.

Reconsidering nuclear is not a unique question for Rhode

Island, according to Christine Csizmadia, senior director of state governmental

affairs and advocacy at the Nuclear Energy Institute (NEI).

NEI, a trade association that advocates for pro-nuclear

policy on the state and federal level, testified in favor of Kennedy’s bill

earlier this year.

Csizmadia said she’s been in the nuclear advocacy space for 18 years, and when

she first started, there were probably five to 10 bills across state

legislatures that mentioned the world nuclear.

“Over the last couple years, there are upwards of 200 bills

every single year,” she said. The proposed legislation looks to end

moratoriums, include nuclear power in green energy standards, set up task

forces to look into the energy, and provide tax credits to nuclear energy

producers.

There were previously 16 state moratoriums on nuclear power,

and six have since been repealed, Csizmadia said, with bills introduced but not

passed to end the policies in Rhode Island and Hawaii.

“We’ve never seen this type of historic momentum toward

nuclear before in history, and so we’re really excited,” she said.

Part of the momentum comes from the push away from fossil fuels, Csizmadia

said, while emerging technology offers the potential to make nuclear energy

cheaper and safer.

Nuclear is already a part of the fight against climate

change, Csizmadia added. Currently, there are some 90 reactors across the

country, producing about 20% of United States energy. That energy amounts to

about half of the country’s carbon-free power, according to the Massachusetts

Institute of Technology’s Climate Portal.

When asked about the safety of nuclear facilities, a major

factor historically in opposition, Csizmadia insisted they are safe and that

she would be comfortable living next to a nuclear power plant. “Oh,

absolutely,” she said, “definitely.”

“The nuclear industry has decades of a very safe, very safe

record,” she said. Deadly incidents at Chernobyl and Fukushima give people

pause, she understands that, she said, and “there’s no reason to not talk about

them and address them.”

The failure at Chernobyl in

what is now Ukraine in 1986 is considered the worst nuclear disaster in

history. The United Nations estimated it killed about 50 people directly from

radiation and likely affected thousands more with long-term health impacts.

The Fukushima disaster

occurred in Japan in 2011 after an earthquake followed by a tsunami shut power

off to the plant’s reactors, causing a meltdown.

Michael Oumano, a member of Rhode Island’s Atomic Energy

Commission, said that while those disasters, along with incidents like Three

Mile Island, have scared people away from nuclear power, it is a very safe form

of energy.

Oumano is a radiation safety officer and a medical physicist

at Brown University and spends a lot of his time determining how much radiation

exposure from things like medical procedures and X-rays is safe.

The federal government regulates how much exposure people

are allowed to get from nuclear power plants, setting it at 1 millisievert (mSv) per year, Oumano

said. A millisievert is a measurement of a radiation dose or exposure,

and 1mSV is one

third of the average exposure Americans get from natural sources, like space

and rocks such as radon. Just from living in the United States, people on

average get exposed to about 3mSvs annually, Oumano said.

“If things are functioning properly, which they do with, you

know, a couple notable historical exceptions, most folks are going to be

limited to 1mSV per year, and likely much, much less,” he said.

A disaster, like Chernobyl or Fukushima, could increase

exposure, but few people die directly from radiation in the immediate aftermath

of a meltdown, Oumano said, although he noted it can be difficult to parse how

many people develop a life-threatening disease, such as cancer, years after an

accident.

Some literature shows more people died in the extensive

evacuations after the Fukushima meltdown than from the incident itself, he

said.

Oumano noted that those disasters will hopefully not be

repeated and wouldn’t likely impact a reactor in Rhode Island.

Chernobyl was caused by a design flaw with the reactor, and

that type of plant isn’t constructed anymore, he said, and Rhode Island is also

safely located away from fault lines and is largely protected from direct hits

from extreme weather.

Oumano said he would live next to a reactor, if one came to

Rhode Island. “If I could see one, I’d be fine,” he said. “I would enjoy the

clean air.”