Charlestown old Naval Auxiliary Air Field was site of heavy use

By Jonathan Sharp

There are still many toxic hot spots left behind by the Navy.

Those acres are now covered by Ninigret Park and the

Ninigret National Wildlife Refuge

However, across the country, there are thousands of

contaminated sites, many of which exceed new limits reported by the Environment

Agency. One of these sites is Rode Island’s Charlestown Naval Auxiliary Landing

Field, home to approximately 2000 people, who are now on the daily exposed to

PFAS as a result of past military activities.

To date, members of the general public can only

receive compensation for PFAS exposure following

class action lawsuits, and the mere presence of PFAS in the blood is not

enough to guarantee compensation.

Rhode Island’s Charlestown Naval Auxiliary

Landing Field

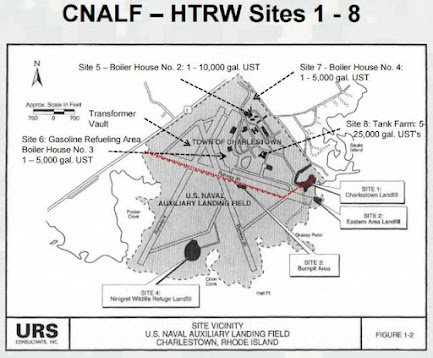

The former

Charlestown Naval Auxiliary Landing Field (CNALF) sits on 630 acres in

Foster Cove and Ninigret Pond. Owned by the U.S. States Navy up to the 1970s,

the area was later divided between the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS)

and the Town of Charlestown.

On the 230 acres granted to Charlestown, numerousmilitary exercises were conducted in the past, including fire drills using per-

and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) under the form of Aqueous Film

film-forming foam (AFFF), and other perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) chemicals.

As these chemicals are highly dangerous to human health and have a high

persistence in the environment, the whole area is under investigation by the

U.S. Environment Agency.

This is not a singular case in the U.S. as over 720

military sites across the country are known to have been contaminated with

PFAS, or the so-called forever chemicals. In total, the U.S.

Environment Agency reports over 7400 contaminated water sites related to

military activities or commercial activities.

As the Department of Defense (DoD) is one of the main contributors to PFAS contamination, persistent efforts have been made over the years to decontaminate these areas and make water safe for the public. However, at present, DoD efforts are concentrated on areas that exceed 70ppt (parts per million) of PFAS in the water. Anything below that does not benefit from decontamination.

Current limits set by the DoD for intervention come

from a 2016 investigation carried out by the

EA’s Health Advisory Commission but have since been reduced for some PFAS

and PFOS to

0.004ppt and 0.002 ppt in light of new evidence

released in 2021 and

2024. With these new limits, the DoD has a

period of five years to decontaminate areas and comply with the new limits.

A total of

42 private and public contaminated wells in Charlestown have been recently identified

by the EA, just under the 70ppt limit, for which the DoD can postpone

intervention. In the meantime, this water serves the local Charlestown

population, not only with drinking water, but also with recreational space,

including playgrounds, picnic spaces, and the Little Nini Pond, which people

use for swimming and fishing.

Decontaminate now or compensate later

There is now sufficient evidence

to demonstrate a clear link between minimal PFAS and PFOS exposure and adverse

health outcomes, especially when a combination of these substances is present

in the water or soil. In the very near future, this evidence is most likely to

grow allowing communities far greater power in court for demonstrating a link

between exposure and disease. Considering this aspect, the DoD will either have

to step up efforts for decontamination or pay later in compensation for the

communities who have been exposed.

Moreover, while the new Vet PFAS Act 2023 does grant

compensation for some conditions, including hypertension, high cholesterol and

some forms of cancer, other conditions that are known in medical literature to be

caused by PFAS still need to be reviewed by a health commission for

eligibility. As the evidence on the causal link between PFAS and multiple

diseases increases, the DoD has fewer and fewer chances to delay the inevitable

and will most likely need to expand the list of diseases caused by PFAS for

which veterans receive compensation.

Rode Island is but one of many locations that could

possibly trigger in future years massive class lawsuits against commercial and

military users of PFAS. Compensating all these populations for diseases that

may develop prior to the DoD’s five-year implementation mark may be more

expensive than decontaminating efforts. Other hidden costs can be added to

these expenses, including medical care, years lost in productivity due to

disability, and legal costs.

About the author

Jonathan Sharp is a Chief Financial Officer at Environmental Litigation Group, P.C.,

responsible for case evaluation and financial analysis. The law firm, based in

Birmingham, Alabama, works with victims of toxic exposure.