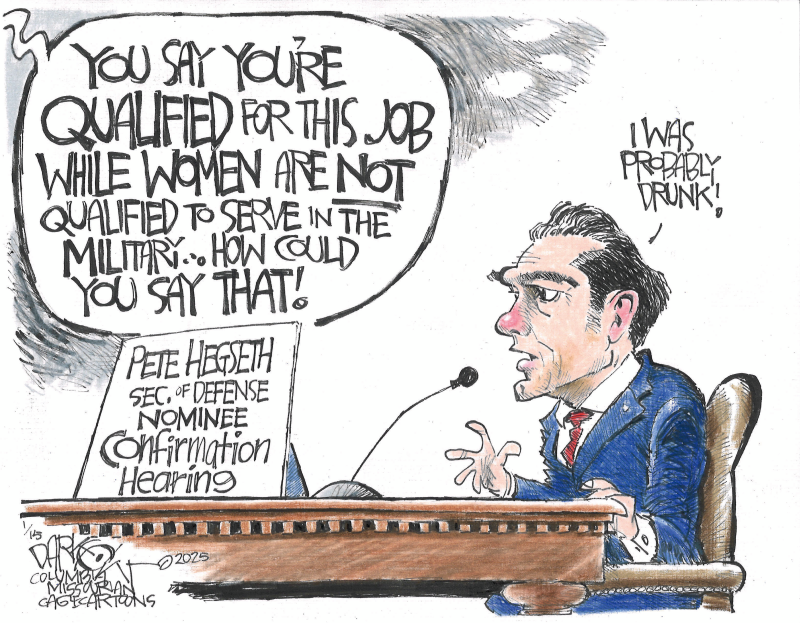

With a guy like Peter Hegseth as nominee for Defense Secretary, how likely is Trump likely to listen to Biden's Surgeon General?

What does this mean for people who drink alcohol and for the

public at large? Peter Monti, a professor of alcohol and addiction studies at

Brown University, has been studying the bio-behavioral mechanisms that underlie

addictive behavior, as well as its prevention and treatment, for several

decades. He led the Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies at the Brown

University School of Public Health for nearly 25 years and is now director and

principal investigator of the school’s Center for

Addiction and Disease Risk Exacerbation.

To Monti, the actions recommended by the surgeon general are

reminiscent of those that public health experts advised in the 1970s to address

the health risks of tobacco. And that effort have been spectacularly

successful, he said.

“Warning labels on tobacco, public education about health risks, communication from doctors about the link between cancer and tobacco usage — these are the kinds of strategies that helped increase public awareness about the health risks of tobacco use,” Monti said. “As a result, tobacco use has decreased significantly. That’s one of the biggest public health successes of the past century.”

As the surgeon general’s report noted, 89% of Americans

recognize tobacco use as a risk factor for cancer, compared to 45% who

recognize alcohol consumption as a risk. Long term, smoking rates have fallen

73% among adults, from 42.6% in 1965 to 11.6% in 2022, according to the American Lung

Association.

In this Q&A, Monti weighed in the advisory and shared

his perspective about alcohol and health risks.

Q: What's the link between alcohol and cancer, and how well

known is this risk among researchers?

As the surgeon general’s report notes, there is extensive

evidence from biological studies that ethanol, the type of pure alcohol found

in all alcohol-containing beverages, causes cancer in at least four distinct

ways. The link between alcohol and breast cancer, particularly among women, has

been known for a long time, so that link is certainly not news to the research

community. While breast cancer has been studied a good deal, we've made inroads

in terms of understanding alcohol’s link to other cancers as well, including

colorectum, esophagus, liver, mouth, throat and larynx.

What's interesting is that the public hasn't appreciated

that link. That could be partially due to the way that information was rolled

out of the National Institutes of Health about 15 years ago. The tone and the

way it was presented just wasn’t helpful for people, and it didn’t help

motivate behavior change.

How doctors talk to their patients is its own area of study,

and presenting information and or misinformation can have important

ramifications. From a public health perspective, whatever we can do to get the

word out with respect to alcohol and cancer is going to move us more in the

direction of what I see as one of the biggest public health successes in the

last 50 years, and that is getting out the word on tobacco use and cancer.

We've really reversed attitudes, beliefs and behavior with respect to tobacco

in a way that I think we could for alcohol, as well.

Q: The surgeon general called for updated warning labels on

alcoholic beverages that make cancer risks clear, in the same way that

cigarettes carry explicit warnings about health risks. Is there a strong enough

link to justify strongly-worded labels?

We have more data now than we've had ever before. The last

couple of decades have provided us with numerous studies making it very clear

that there's a solid link between alcohol and cancer, and given the downsides

of not saying anything, it does make sense to get this out on the labels now.

In fact, we should have done this years ago.

It should be noted that there hasn’t been a study where some

people have been randomly assigned to drink one alcoholic beverage a day and

other people have been assigned to drink no alcohol at all, with all followed

over time. That type of study would be very expensive, and some of the health

effects would take months and years to develop. Those studies have been

conducted with lab animals, and there has been clear evidence of the negative

effect of alcohol. Ultimately, a randomized control study with humans is what

we need to conclusively prove a causal link between alcohol consumption and

cancer. But in the meantime, we have a lot of persuasive evidence.

Q: Do you think is cancer is the biggest health risk of

alcohol consumption and the one that drinkers should be most worried about?

It certainly is one of the biggest risks. The other big risk

is cardiovascular disease, particularly atrial fibrillation, which is an

irregular, often rapid heart rate that commonly causes poor blood flow —

there are clear links between alcohol consumption and atrial fibrillation. The

risk between alcohol and cardiovascular disease is an emerging research area

that that I think will get lots of attention in the years to come.

Q: Does the risk change in terms of the type of alcohol that

is consumed?

It's a myth that if you drink beer or wine you're less

susceptible to the negative effects of alcohol than if you drink hard liquor.

The research does not support that at all.

Q: Does the amount of alcohol matter?

Yes. Alcohol is broken down in the body into acetaldehyde,

which is a metabolite that binds to our DNA. And when it does so, it damages

the DNA and allows the cell to which it binds to grow out of control, and to

ultimately form into a cancerous tumor. Multiple studies with rats and mice

have shown that ethanol results in tumors at multiple places in the body. The

more alcohol one consumes, the more acid acetaldehyde is likely to bind to the

DNA, and the higher likelihood of tumor growth.

The last couple of decades have provided us with numerous

studies making it very clear that there's a solid link between alcohol and

cancer, and given the downsides of not saying anything, it does make sense to

get this out on the labels now. We should have done this years ago.

Q: The report explains how cancer risk is affected by

alcohol, using this example: A study of 226,162 individuals reported that the

absolute risk of developing any alcohol-related cancer over the lifespan of a

woman increases from approximately 16.5% for those who consume less than one

drink per week, to 19.0% for those who consume one drink daily on average, to

approximately 21.8% for those who consume two drinks daily on average. Is that

a big difference?

It's certainly a difference worth noting. It would be enough

for me, particularly if I had other risk factors for cancers like genetics,

environmental stressors, etc.

Another way to view it is that alcohol is the third leading

preventable cause of cancer, after tobacco and obesity. So if you don’t smoke

and you are able to prevent becoming overweight and don’t drink (or cut down on

your drinking), your cumulative risk is going to go down exponentially. That

may be very motivating for some people.

Q: Does research show that warning labels are an effective

way to increase awareness around the risks of addictive substances?

I think there's proof positive in tobacco. The warning

labels on cigarettes have proven effective in increasing awareness of cancer

risk and decreasing use.

Q: In addition to warning labels, the advisory calls upon

public health professionals to highlight alcohol consumption as a leading

modified cancer risk and strengthen, expand education efforts to increase

general awareness, and reassess guideline limits for alcohol consumption to

account for cancer risk. What do you think of these recommendations?

I agree that there needs to be an all-hands-on-deck

approach. The recommendations by the surgeon general in the report are the

kinds of tactics that we have seen work to increase awareness of the health

risks of tobacco.

Q: In the report, the surgeon general talked about a need

for research on questions including, for example, how specific patterns such as

binge drinking may affect cancer risk. What research questions do you have?

I think that looking into the pattern of alcohol use would

be very informative, because we know that a lot of people think abstaining

during the week and bingeing on the weekend is healthier than drinking

moderately every day. (That's not the case, by the way.) We have recently had

many researchers studying alcohol and the adolescent brain, and I think that

linking their findings to the development of cancers would really advance our

understanding of alcohol and health risks.