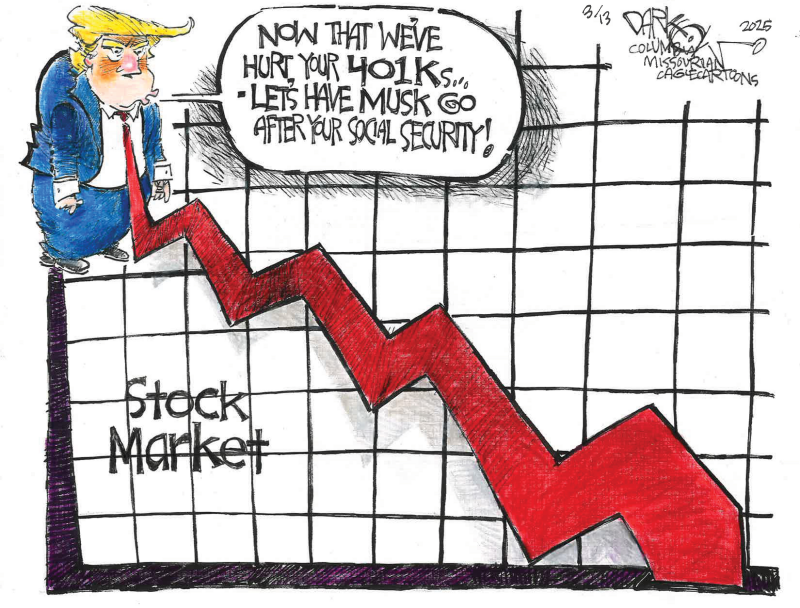

Are you ready for anarcho-capitalism?

Donald Trump has directed the executive branch to “significantly reduce the size of government.” That includes deep cuts in federal funding of scientific and medical research and freezing federal grants and loans for businesses.

He has ordered the reversal or removal of regulations on medical insurance companies and other businesses and sought to fire thousands of federal employees. Those are just a few of dozens of executive orders that seek to deconstruct the government.

More than 70 lawsuits have challenged those orders as illegal or unconstitutional. In the meantime, the resulting chaos is preventing the government from carrying out its everyday functions.

The administration accidentally fired civil servants who were responsible for safeguarding the country’s nuclear weapons, preventing a bird flu epidemic and overseeing the nation’s electricity supply.

A Veterans Administration official told NBC, “It’s leading to paralysis, and nothing is getting done.” A spokesperson at a nationwide program that provides meals to seniors, Meals on Wheels, which the government helps fund, said, “The uncertainty right now is creating chaos for local Meals on Wheels providers not knowing whether they should be serving meals today.”

Our recent book, “How Government Built America,” shows why the administration’s aim to eliminate government could result in an America that the country’s people have never experienced – one in which free-market economic forces operate without any accountability to the public.

.webp)

.webp)

.JPG)