Energy matters make consumers question costs

As the U.S. pivots on energy policy and priorities, consumers are talking about their energy bills, approaching the issue from a personal perspective, wondering why the cost for delivery can be higher than that for the actual energy, and worrying about current and future prices.

Corey Lang, an environmental economist and

professor in the University of Rhode Island’s College of the Environment and

Life Sciences, conducts research at the intersection of energy and residential

issues, focusing on ways energy issues interact with the public interest.

Lang says that many Rhode Islanders have experienced a large

increase in electricity bills in recent months, stemming from this winter’s

abnormally cold and windy weather leading to increased usage.

“Utilities are in the business of distribution,” says Lang.

“It costs a lot of money to build and repair the distribution network, keeping

electricity flowing efficiently and reliably.”

In URI’s College of Business, Douglas

Hales, professor of operations and supply chain management, is

focusing on global supply chain management.

Hales discussed the reasons for consumer price flux in

energy bills in an interview.

How does energy distribution work?

Energy comes from two primary distribution channels and six

energy generation methods.

Distribution can be local, coming from solar panels or fuel

powered generators onsite; or from a grid that delivers it from a remote

location, where the power is generated, to user location through wires running

overhead on power poles. Regardless of the method, all power must be converted

from its natural/source form into AC current (Alternating Electrical Current)

in order to be useful.

The generation methods used here in New England are 52% by

natural gas generators, 26% from nuclear power plants, 12% solar farms and wind

turbines, 7% water dams, 2% fuel oil generators, and .31% coal-fired plants.

Each of these methods are located in different geographic locations so it is

expensive to bring the power from different locations to the grid.

Additionally, when distributing power from the source to

homes, power is lost. On average, a power plant must generate twice as much

energy as is needed, meaning that a plant must produce 200 watts of power to

light a 100-watt bulb in a home or business.

What’s been happening in energy prices this winter?

Because it is a harsh winter, there is less sunlight than

previous recent winters so solar farms aren’t producing as much power this

winter as usual. And because of this year’s harsh weather, demand for power is

up. For instance, on Jan. 19 this year, at 6 p.m., there was a peak demand for

19,600 megawatts of electricity in the five New England states.

Because of higher demand for electricity, the power company

had to use more oil and coal generators than normal to make up the difference.

The next two days, Jan. 20-21, during daytime peak hours, there was more power

generated for New England by oil and coal-fueled plants than by natural gas

(the usual leader at 52%). Because the natural gas plants, nuclear plants,

solar and wind farms, and water dams almost always run at maximum capacity

year-round, the only way to make up for a spike in electricity demand is

through the use of fuel oil and coal-fired plants, which are more flexible to

start up and stop.

Because demand is higher, costs are also higher. Research

indicates that even if the electricity rates do not increase, consumers see

higher electricity bills because of more use. However, now that more fuel oil

and natural gas is being used to generate power for the grid, the price of fuel

oil delivered to homes and businesses increases on each fill, and the price of

natural gas has risen accordingly. Oil and gas prices are not regulated by the

government, so they change with demand. Electricity prices come from a grid and

are regulated by the government.

What is the reason for delivery charges being higher than

the cost of energy and what can consumers expect to see in their energy bills

going forward?

There are two costs involved: a cost to generate the

electrical power and a cost to deliver the power. It is more costly to deliver

power this winter because labor, and material and equipment (wire,

transformers, service trucks, etc. due to inflation) costs are up due to the

harsh weather and a shortage of spare parts. In harsh winters, more material

and equipment are damaged and need replacing and repairing. More labor hours

are needed on overtime pay. This year the distribution maintenance costs rose faster

than the power generation costs. Long-term, people can add solar panels that

can replace electricity from the grid, and while the costs for solar panels are

dropping, there is an upfront cost of adding a solar system to your home. In

Rhode Island, the power company will pay you for unused solar energy that your

panels produce, but this has consequences that users should investigate before

installing.

What can New Englanders expect to see in energy use and

changes in our area?

In the short-term, harsher winters here in New England

equate to more power usage. While rates for electricity won’t change, the

amount of power used will increase in harsh winters. But the rates for natural

gas and oil aren’t regulated so their prices can change on every fill up.

Is there anything you recommend consumers do, to save

money or be better informed on energy issues?

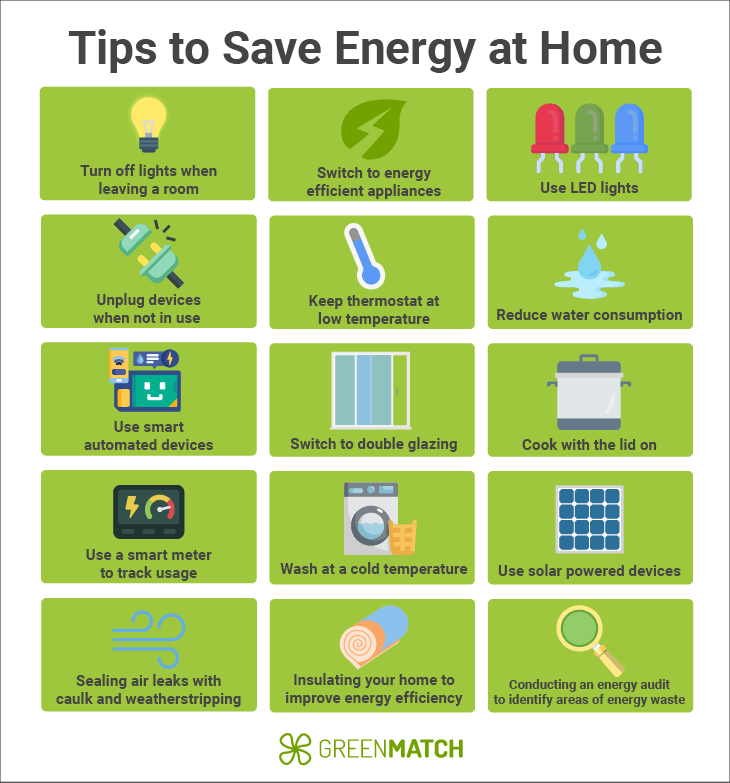

Electricity rates are regulated so they won’t change within

a season, so power bills are in full control of the user. Keeping control of

the thermostat is essential. The recommended level is between 66 and 68

Fahrenheit for heat. Check for heat loss through drafts from windows and doors.

Insulation in the walls, attic and floor can help. Electric or gas hot water

heaters with temperatures set at 115 to 120 F can save substantial energy over

those set at 125 to 130 F. A few degrees can make a huge difference on power

bills. Consider turning the temperature in your home to 60 to 62 F when no one

is at home for a few hours, and if you are leaving for a few days, consider

turning your hot water heater down to 100 to 105 F.

Electric clothes dryers are one of the largest users of

power in a home. Make sure that clothes from the washer are spin-dried as much

as practical and the electric dryer is full to manufacturer recommendation when

running. Too many small loads can increase electricity waste. This is true for

electric dishwashers as well. Because dishwashers have electric pumps, heaters,

and spin motors, too many small loads can increase electricity bills. Fuel oil

and natural gas rates are not regulated and can change at any time, so these

bills are partially out of control of the user.

Lang adds that it’s important for consumers to look at their

bills and assess if they’re getting the best rate.

“These rates are regulated and only change every six months,

and even then are fairly consistent. The cost of electricity is almost

independent of the cost of distribution. Some customers pay more for

electricity than distribution, and some vice versa,” says Lang.

“Rhode Island Energy allows customers to choose their energy provider, so it’s important for customers to determine if their rates are better or worse than the state’s ‘Last Resort Service’— the guaranteed rate provided by Rhode Island Energy. If their rate is higher, then they might want to consider switching.”