Elon Musk Is the Reason Social Security Is “Running Out of Money”

Before we dive in, let’s get one thing straight. Social Security is a federal program that was created under the Social Security Act of 1935. It was established as part of the New Deal by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt with a “dedicated revenue” in the form of a payroll tax. Today, employees and their employers each pay 6.2% of wages up to a taxable maximum of $176,100 (2025) into Social Security. ¹

I’ve been publishing academic and popular articles

on Social Security for at least 25 years, trying—unsuccessfully—to shift the

public debate away from concerns over “financial solvency” toward a focus on

inflation risk and real resources. As far as I’m concerned, any lawmaker,

journalist, or media pundit who talks about Social Security without

distinguishing between the following challenges isn’t being honest with

American people.

1.) Legal Authority to Pay — Under current

law, Social Security can only pay full scheduled benefits if there is enough

earmarked funding to do so. Put simply, there must be enough “cash” coming in

via payroll tax withholdings or enough “cash” coming in plus “cash”

in the Social Security Trust Fund to cover the full cost of paying benefits

each year. If the trust funds run dry—i.e. are drawn down to zero—then the

program doesn’t have the legal authority (from Congress) to

pay full benefits. This would force automatic cuts under current law. ²

2.) Financial Ability to Pay— As Alan Greenspan explained under oath many years ago, the federal government cannot “run out of money.” One does not have to embrace Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) to acknowledge that Congress has the financial ability to “create as much money as it wants and pay it to someone,” as Greenspan put it. Social Security is a federal program, authorized to pay benefits to eligible individuals—retirees, their dependents, and the disabled—under the rules established by Congress.

The reason there is so much anxiety about Social

Security “running out of money” is that the authority to pay

benefits is constrained by statute. If Congress changed the law to

give Social Security permission to pay full scheduled benefits regardless

of any earmarked source of funding, then the threat of automatic cuts would

disappear.

3.) Capacity to Provide Real Resources—This is

where the rubber meets the road, and this is what MMT economists emphasize. It

is easy enough for a currency-issuing government, like the United States, to

meet financial obligations that are denominated in a sovereign unit of account.

That’s true whether we’re talking about paying trillions of dollars in interest

on government securities or trillions in the form of benefits to future

retirees. In purely financial terms all of it is “affordable.”

But what about in real terms?

Greenspan understood this point quite well. How can you be sure, he asked, “that the real assets are created which those benefits are employed to purchase?” In other words, what happens after the checks go out and retirees—who are no longer helping to produce the economy’s output—want to book vacations, dine out, play golf, get medical treatment, and so on? With fewer workers and more retirees, the real challenge is this: Will the economy be productive enough, in the year’s ahead, to allow both groups to buy the things they want or will everyone end up competing over a shrinking pool of real resources, thereby driving up prices?

Running Out of Money

If we were having an honest debate, we would acknowledge

that Social Security can run out of statutory headroom to pay full scheduled

benefits, but the money can always be made available. Alas, we’ve become

trapped in an eternal tug-of-war over the program’s “solvency,” not unlike two

desperate souls fighting over rocks in Dante’s Fourth Circle of Hell.

Everyone just accepts that the program is “running out of

money,” so there’s a never-ending battle over the best way to shore up the

program’s finances. It’s not the debate I want to have, but it’s the only one

that gets any serious consideration.

So it’s worth understanding how the Social Security

Administration (SSA) determines how much runway is left before the program

“runs out of money.” It’s actually a pretty big undertaking, and it

requires the Trustees of the SSA to make a wide array of economic and

demographic assumptions in order to project how much money the program will

take in—and pay out—in future years. Here’s a

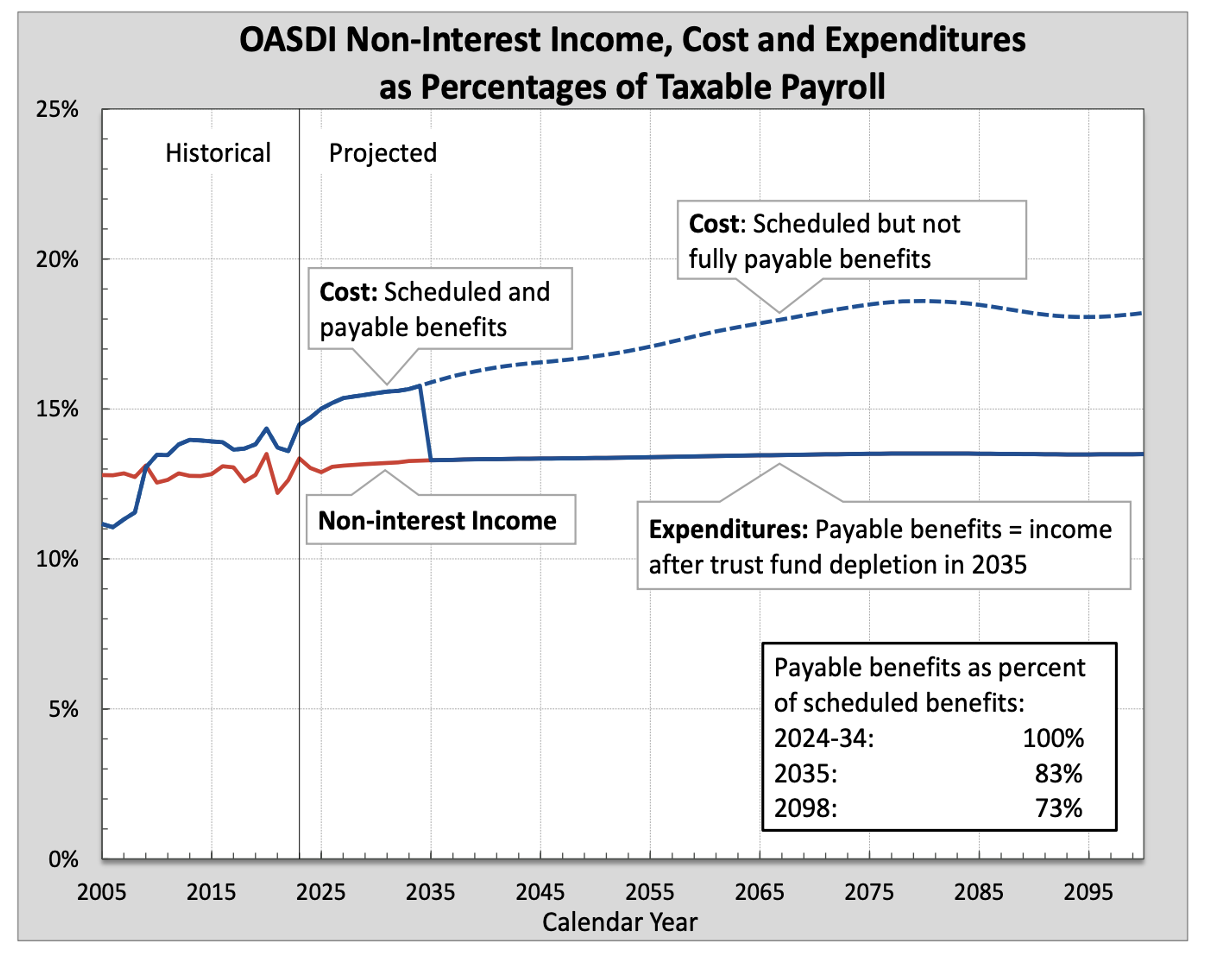

projection from the chief actuary of the SSA, Stephen Goss:

There’s enough “money” to pay full scheduled benefits until 2035. After that, the combined (OASDI) trust fund (which doesn’t actually exist), is depleted and the program is only legally authorized to pay 83% of scheduled benefits. The “good news” is that this is projected to happen 13 months later than the Trustee’s were forecasting in their previous year’s report.

If that seems like a pretty big “miss,” it’s because it’s

hard to predict exactly what’s going to happen to things like inflation,

unemployment, economic growth, worker productivity, fertility and mortality

rates, immigration, etc. Relatively small changes in the underlying assumptions

can have a big impact on the size and timing of projected shortfalls. ³

The Shortfalls Weren’t Supposed to Happen

Back in 1983, following the prescriptions of the Greenspan Commission,

changes were made that were supposed to prevent Social Security from “running

out of money” over the next 75+ years. Yet here we are, in the Fourth Circle of

Hell, wringing our hands over looming shortfalls and automatic benefit cuts.

But why? As Stephen Goss put it:

Why are we now facing OASDI Trust Fund reserve depletion in 20235, almost 30 years earlier than projected in the 1983 report, after enactment of the 1983 Amendments?

Well, it turns out that some things are easier to predict

than others. As Goss explains,

it’s not that people are living longer than expected. In fact, “projected life

expectancy at age 65 in the 1983 report was extremely accurate.” It’s also not

because of an unexpected decline in birth rates, for “this was also known and

anticipated in 1983.”

The main issue—what the Greenspan Commission did not see

coming—was Elon Musk. Or, more specifically, the “increasing concentration of

earnings at the top of the distribution.” As Goss explains:

“The reduced share of earnings subject to payroll tax explains most of the increase in cost as percent of payroll, compared to the 1983 projection.”

In other words,

rising inequality is the main reason that Social Security appears to be in

financial trouble.

Bottom Line

The bottom line is that if you want to engage productively

in the debate over Social Security, you need to understand the difference

between legal authority to pay, financial ability to pay, and real resource

capacity. If you simply want to understand why pretty much everyone believes

the program is “running out of money,” you need to understand how the Trustees

formulate their projections. And if you want to understand why the Trustees

continue to project shortfalls when the whole “problem” was supposedly resolved

back in 1983, you need to understand the one big thing the Greenspan Commission

didn’t see coming: the rise of Elon Musk. ⁴

The Lens is a reader-supported publication. To receive new

posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Footnotes

- The

self-employed pay 12.4%, since they’re paying the employee and employer

side. While benefits are highly progressive, the payroll tax itself is by

far and away the most regressive tax in America.

- The

Social Security Administration estimates that Social Security can pay 83%

of scheduled benefits after trust fund depletion in 2035 and 73% of

scheduled benefits in 2098.

- For

example, over the past 13 years (2012–2024), the Trustees have projected

that the Social Security Trust Fund (OASDI) would be depleted sometime

between 2033 and 2035. ut over the past 30 years (1995–2024), they thought

this could happen as early as 2029 or as late as 2042.

- I’m

obviously using Elon Musk to make a more general point about trends in

inequality.

Stephanie Kelton is a leading authority on Modern

Monetary Theory, a new approach to economics that is taking the world by storm.

She is considered one of the most important voices influencing the policy

debate today. Her New York Times bestseller, The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary

Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy, shows how to break free of the

flawed thinking that has hamstrung policymakers around the world. In addition

to her many academic publications, she has been a contributor at Bloomberg

Opinion and has written for the Financial Times, The New York Times, The Los

Angeles Times, U.S. News & World Reports, CNN, and many others. Professor

Kelton has worked in both academia and politics. She served as chief economist

on the U.S. Senate Budget Committee (Democratic staff) in 2015 and as a senior

economic adviser to Bernie Sanders’ 2016 and 2020 presidential campaigns. She

is a Senior Fellow at the Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis and a

Professor of Economics and Public Policy at Stony Brook University. Stephanie

has held Visiting Professorships at The New School for Social Research, the

University of Ljubljana, and the University of Adelaide. POLITICO called her

one of the 50 Most Influential Thinkers in 2016, Bloomberg listed her as one of

the 50 people who defined 2019, Barron’s named her one of the 100 most

influential women in finance in 2020, and Prospect Magazine listed her among

the world’s top 50 thinkers in 2020. She was previously Chair of the Department

of Economics at the University of Missouri, Kansas City.